What the Three Most Popular Cars in History Have in Common

THE THREE MOST POPULAR CARS ever made have this in common: they were cheap, they retained their basic design for decades, and they invited repair by the owner. The Ford Model T sold 16.5 million between 1908 and 1927. The Volkswagen Beetle sold 21.5 million between 1938 and 2003. The Lada Classic from Russia sold 18 million between 1970 and 2012.1 (Other cars with best-selling reputations, such as the Toyota Corolla, Toyota HiLux, and Ford F-series, retained only their brand names while changing radically in design.)

A Lada owner in Borovsk, Russia, working on the exhaust system in 2019

Tools provided with each Lada.

Just as Henry Ford in 1908 designed the Model T for a dirt-road America, the designers of the Lada in 1973 (it was just a beefed-up Fiat sedan) were realistic about what their customers would have to deal with in the Soviet Union. The country was vast, the roads terrible, and the winters brutal. There were no repair shops. Fuel quality was unreliable. Potential customers had barely any money.

So Ladas were made as cheap as possible. (A joke of the time asked, “How do you double a Lada’s value?” Answer: “Fill it up with petrol.”) One driver recalled the Lada’s

strangely brittle plastic, lumpy foam and clingingly uncomfortable fabric, hideously inadequate fittings, parts that came off in your hand when using them; erratic gauges, either wildly optimistic or non-functioning; keys that broke in the locks; seats that listed drunkenly.2In their favor, the Ladas were ruggedized with thicker steel panels than the original Fiat, higher road clearance, and sturdier transmission and brakes. The engine ran roughly, but it could handle any fuel. Since the cars required constant maintenance, they were designed so that the owner could do the work. Each Lada came with a set of tools for fixing it. The windshield wipers were made to be easily removed because, in Russia, if the driver didn’t lock them inside the car when parked, they would be stolen.

The Lada had a continuity advantage similar to Ford’s Model T—it remained in production virtually unchanged for 32 years. Consequently, as a recent article points out, “While the car was notoriously unreliable, it was also ridiculously easy to fix. You could pluck a part from virtually any Lada ever made, jam it into yours, and get it going again.”3

For many in Russia and the Eastern Bloc, and for millions of Lada export customers worldwide, it was their first car, and loved accordingly.

Hippies painted everything they owned. This was my VW van in 1968.

Volkswagens were similarly loved by my generation of hippies in the 1960s and ‘70s. Along with the 21 million VW bugs, some 12 million boxy VW vans with the same air-cooled engine as the bug were sold between 1950 and 2013. My van was made in 1962. I painted it military-spec jungle camouflage with a general’s star on the door and often lived in the back, which I customized with plywood into an inviting bed.

The American appetite for “do-it-yourself” began long before our time. Farms and ranches had always depended on do-everything-yourself skills. A kid growing up there spent all day on maintenance chores, learning from older family members and ranch hands how to fix the tractor, mend barbed wire fence, manage the wood stove, and do the laundry. By the early 20th century, servants were disappearing in towns, and home ownership was taking off. By the 1950s, doing one’s own home repair and improvement became a popular pastime on weekends. Retired males had a shop in the basement or garage. Teenagers hot-rodded their cars.

But as cars became more complex and costly, professional mechanics took over more and more vehicle repair. If your car needed work, you were supposed to take it back to the dealer, and that turned out to be expensive and frequent.

We hippies were so set on escaping dependency, we wouldn’t listen to our elders, or professionals, or even to knowledgeable neighbors. So instead, we relied on books to teach us how to garden, raise goats, build geodesic domes, and all the other “basics” that we were determined to “go back to.” Most of the generational techniques and tools that hippies sought could be found in one place—the Whole Earth Catalog, a do-everything-yourself compendium I co-founded and edited from 1968 to the early ‘80s. Of course one whole page was devoted to taking care of our VWs. The star of the page was one of the best repair manuals ever created: How to Keep Your Volkswagen Alive, written by John Muir and illustrated with pizazz by Peter Aschwanden.

Hippies had a peculiar aspiration about money. We aimed to live as adventurously as possible on as little money as possible. Travel was by hitchhiking or driving the cheapest car we could find—the Volkswagen. Our self-reliance imperative required that we repair it ourselves. John Muir saw that desire and met it with something revolutionary, a self-published book with a cheery, dead-accurate subtitle: A Manual of Step-by-Step Procedures for the Compleat Idiot. He assumed, rightly, that his readers had a funky car with funky problems and no idea how to solve them.

First self-published in 1969, John Muir’s How to Keep Your Volkswagen Alive remains alive itself to this day—currently in its 19th edition with updating by Tosh Gregg and illustrator Peter Aschwanden. Air-cooled VWs have not been manufactured since 1980 (except for a few in Mexico up till 2003). The continuing popularity of Muir’s book indicates a hell of a lot of VWs have been kept alive, probably via his manual.

Muir organizes the book around the problems, with chapters titled: Engine Stops or Won’t Start; Red Light On! (Generator or Alternator); Green Light On! (Oil); Maintenance (3,000 Miles); Volkswagen Doesn’t Stop (Brakes); Shimmies and Shakes (Front End); Slips and Jerks (Clutch); Grinds and Growls (Transaxle).

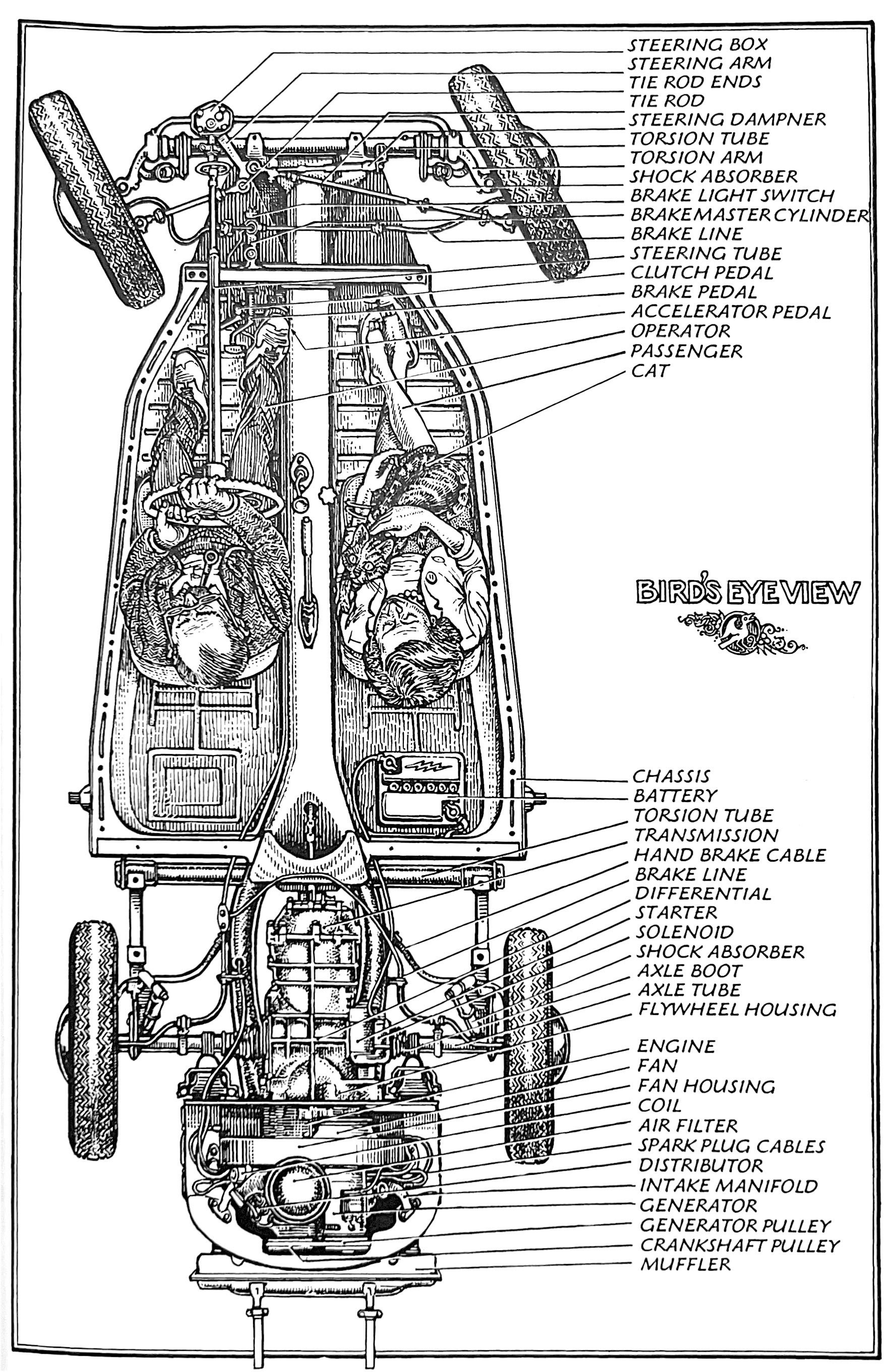

John Muir’s manual provides an overall understanding of the car’s workings and nomenclature as well as exhaustive details on how to fix everything.

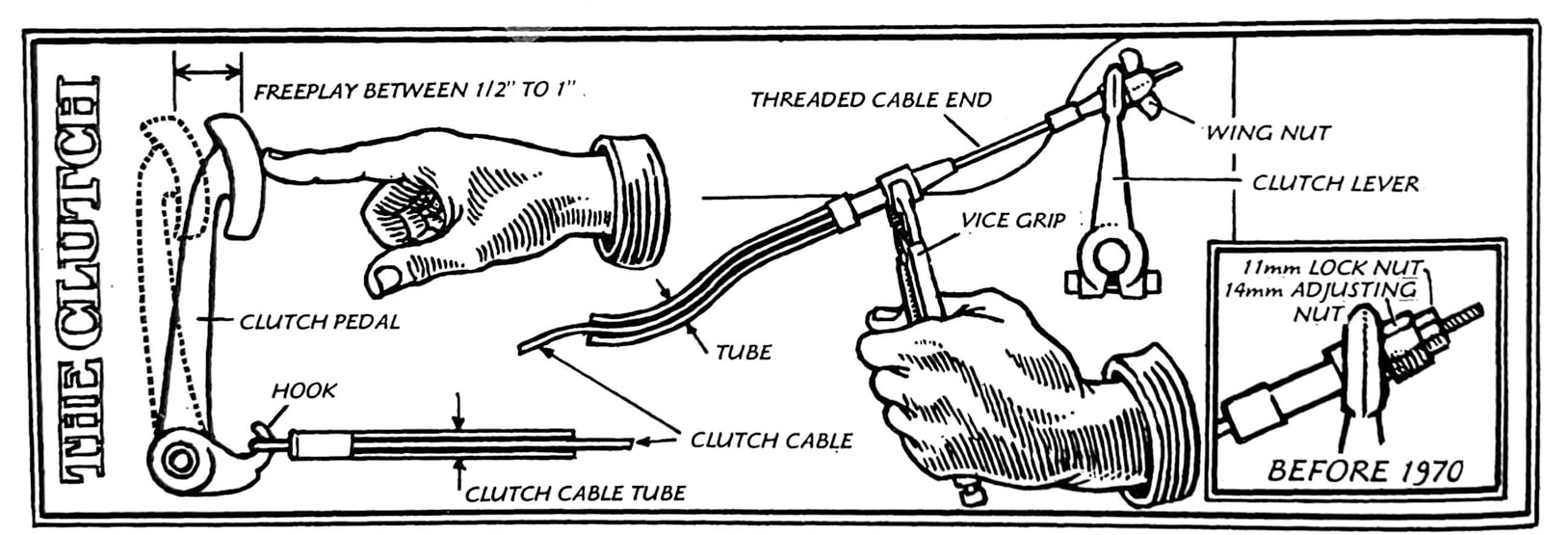

John Muir on adjusting the VW’s clutch: “Take the vice grip, the 14mm and 11mm end wrenches, plus the flashlight for locating things with you under the car. Scrooch under the car with your head almost under the left rear axle. Look up.” So begins his meticulous directions, including notice that if your car was built in 1970 or after, you don’t need the end wrenches; your fingers are sufficient to turn the wing nut. This drawing covers both alternatives.

Muir teaches how to listen for problems. If there’s a funny noise and pushing the clutch down silences it, it’s a transmission problem, but if it changes to a different funny noise, it’s a clutch problem. “Loose valves tweedle,” Muir writes; “Very loose valves clatter.”4 He gives his reader the confidence to undertake even heroic tasks like diving into the engine’s guts to adjust the valves every three months. He writes in capital letters: “DOING THE VALVES, TIMING, AND MINOR MAINTENANCE ON YOUR OWN CAR WILL NOT ONLY CHANGE YOUR RELATIONSHIP WITH YOUR TRANSPORTATION BUT WILL ALSO CHANGE YOUR RELATIONSHIP WITH YOURSELF!”

(That general point is still valid, but car tune-ups are a thing of the past these days. Items like the carburetor and distributor that needed frequent adjustment have been entirely supplanted by electronic fuel injection and computerized ignition systems that adjust themselves. The new platinum sparkplugs are so durable they seldom need checking or replacement. Those things came because low-maintenance sells. That fact is a key driver of progress in the world.)

While Muir teaches his readers every kind of repair their VW might ever need, he teaches them especially how to avoid having to do it. He advises: “Warm up the engine before moving—ninety percent of engine wear happens in the first fifteen minutes of operation. Warming up the engine is a sacred rite…. Do this warm-up thing and it will make your VW last a third longer, minimum.”5 He recommends that you idle for at least half a minute (up to three minutes in cold weather), then drive gently for the first mile. The point, he explains, is to give the engine cylinders time to get fully coated with oil. “Now when I put a load on the engine, it is the oil that carries the load, not the metal.”6 Modern engines are no longer so delicate about needing a warm-up, but their requirement for consistently renewed oil hasn’t changed a bit.

Hippies were so dedicated to “living in the moment” that preventive maintenance was a difficult lesson for us. Something breaking is a big event. Repairing the broken thing is a big event. Preventing the thing from breaking is a non-event. Doing a responsible task like changing the oil does not come naturally. It is a messy chore, tedious and thankless. There’s no reward when you do it and no reward later—just the unnoticeable absence of pain. To acquire the adult discipline of preventive maintenance, us flower children had to learn at soul depth the remorseless logic of “An ounce of prevention is worth a ton of cure.”

For example, being oblivious and lazy about the oil in a Volkswagen, Muir points out, leads inexorably to a “tickety” sound in the engine becoming a “tockety” sound, and then a connecting rod bearing gives out and the broken rod bursts through the crankcase, at which point your car is not only dead in the road, you’ve got to buy a new engine.

Once the pain of avoidable repair is severe and repeated a few times, the attraction of heading off the pain with preventive maintenance becomes compelling. Then all we need is knowledge of what to do and when and how to do it. The universal advice from professional maintainers to every impatient equipment misuser is an expletive: “Read The Fucking Manual!”

By which they mean: Part of taking proper ownership of something is to study its manual first. Owner’s manuals, along with offering a good introduction to the thing owned, are usually informative on preventive maintenance, and most provide a trouble-shooting section for simple fixes. If you take the thing to a professional for what turns out to be something minor that is thoroughly covered in the manual, they may well charge you extra for being obtuse and annoying. If you ask online for a solution, you’ll get the acronym version: “RTFM!” —typically used, says Wikipedia, “to reply to a basic question where the answer is easily found in the documentation, user guide, owner's manual, online help, internet forum, software documentation, or Frequently Asked Questions.”

The Whole Earth Catalog eventually faded from usefulness, along with most printed manuals, because they were totally replaced by the Internet. How that played out is worth another Digression.

___________________________