Three Maintenance Philosophies Fought for Control of the Auto Industry

AA FUNDAMENTAL QUESTION that will keep coming up is this: What are the best ways to design for maintenance? At the very beginning of the auto industry, no less than three radically different design-for-maintenance philosophies fought it out. One lost, but not because of maintenance issues. The other two won big by rejecting each other’s approach to maintenance.

1899. Looking exactly like horseless carriages, the first electric cars were simple to drive and maintain. This gentleman wore formal dress at the tiller of his early electric. (Steering wheels came later.)

Electric automobiles were the first to market, almost fully formed by the 1890s. Technology historian George Basalla writes:

The electric car appeared to have all of the good points of the horse and buggy with none of its drawbacks. It was noiseless, odorless, and very easy to start and drive. No other motor vehicle could match its comfort and cleanliness or its simplicity of construction and ease of maintenance. Its essential elements were an electric motor, batteries, a control rheostat to regulate speed, and simple gearing. There was no transmission and, hence, no gears to shift1By the first decade of the twentieth century, dozens of manufacturers in America and Europe were offering electric automobiles. New York, London, and Paris had fleets of electric taxis and delivery vehicles.

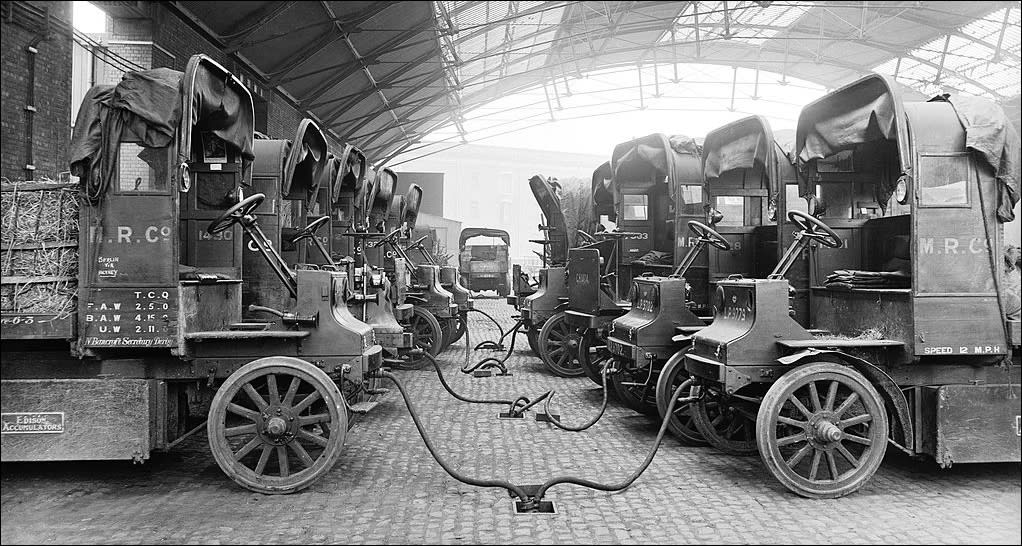

Electric lorries being recharged at St. Pancras Station, London, 1917. The Midland Railway Company had a fleet of 84. During World War I (1914-1918), the War Office encouraged the use of electric vehicles to free up petrol and horses for the military. The wooden wheels on these trucks indicate they may have been manufactured in the US. Certainly the batteries were—the metal plate at lower left reads “Edison Accumulators.”[1] Thomas Edison patented, promoted, and sold nickel-iron batteries that he claimed were better than the standard lead-acid batteries of the time. They were remarkably maintenance-free and long-lasting, but their low efficiency and high cost kept them from taking over the market.

Gasoline-powered internal combustion engines were arriving at the same time, but they were a pain to run. Owners who could afford it hired a chauffeur to repair and drive the complex machines. The electric vehicles were so easy to use that they were marketed especially to women. An advertisement for Rauch & Lang Electrics listed the advantages:

Electric Car SupremacyEvery member of your family can drive it—no chauffeur needed. It offers all of the best qualities of a gasoline car without any disagreeable features—danger from gasoline—-offensive odors of oil-—grime, dirt, and the difficulties attending its operation…. Its upkeep is far below that of the gas car, to say nothing of the depreciation difference…. No machinery to get out of order—no mechanician needed—no engine trouble—no nerve racking gear clashing—no exhaust noise to disconcert the timid—nothing, but just the enjoyment of rapid transit in an easy, luxurious, delightful manner.2

A woman poses with a hand-cranked battery charger for her electric Columbia Mark 68 Victoria automobile in 1912.

Electric cars scored high on all the issues of vehicle maintenance. Compared with gasoline engines, they had far fewer moving parts and almost none of the problems that come with fluids: no explosive gasoline, no scalding water steaming out of the radiator, no oil to change. The electrics ran cool and quiet, with none of the high temperatures and percussion of internal combustion engines. Only the lead-acid batteries needed frequent attention—their water had to be checked and refilled, the accumulated sludge removed, and the positive plates cleaned.

The main limitation of the electrics was the short distance they could travel on a battery charge. Since they were at their best in cities, they were tailored for the urban wealthy with luxury items such as “upholstered chairs, clock, reading lights, lady’s toilet case, gentleman’s smoking set, flower vase of cut glass, and silk curtains,”9 according to one chronicle of the age. Shopping districts lured affluent customers with free charging stations. Owners who could afford it hired service centers near their homes to pick up, charge, clean, and maintain their electrics at night and deliver them the next day. The cars were stabled at night, like a horse.

Henry Ford’s wife Clara loved her 1914 Detroit Electric Model 47 Brougham (a brougham had a roof over the passengers but not the driver) and drove it well into the 1930s, while her husband’s mass-produced Model T’s were displacing cars like hers from the world. A deluxe electric like Mrs. Ford’s cost $3,000. The Model T’s cost $300.

And other forces were at work. Gasoline got steadily cheaper, thanks to widespread petroleum discoveries. The invention of the electric self-starter in 1912 was a breakthrough: drivers no longer had to risk broken teeth or a dislocated shoulder hand-cranking their car to start it. All they had to do was push a button. In addition, bicycle enthusiasts had founded the Good Roads Movement to force the government to pave rural roads, and the early drivers of touring gas cars joined the movement. As soon as dirt roads began to be paved in the 1920s, gas cars sped far into the countryside and left the city-bound electrics behind.

Maintenance for electrics was easy thanks to their simplicity. A completely different kind of low maintenance arrived with the most epic exploit in early automobile history.

It took place in England and Scotland in the summer of 1907. The demonstration model of a new internal combustion car was driven for 40 days straight, 14,000 miles over mountainous country, in all weathers, at up to 80 miles an hour. An official judge from the Royal Automobile Club was on board to chronicle the number and nature of breakdowns during the endurance test. He recorded no breakdowns at all—apart from the occasional stops to repair tire punctures common to all vehicles then. (A car doesn’t just have moving parts; it is a moving part.)

Though the car was still running perfectly at the end of the test, the manufacturer disassembled the entire vehicle anyway, just to see which parts showed signs of wear. Several pins and a fan belt were replaced, and a valve was reground. That was all. The company made sure that everything about the test and its results were celebrated in the press.3

The manufacturer was Rolls-Royce. The car was called the “Silver Ghost,” so named because of its swanky color and stealthily quiet running. Its price was high, but buyers deemed it an investment. They figured that the value of a durable, gorgeous car widely described as “perfect” could only increase with time. Sure enough, a century later, most of the early Silver Ghosts are still running—each one worth a fortune.4 (In 1921 a Silver Ghost was purchased in America for $12,000--about $190,000 in current dollars. According to Classic.com, of 31 Silver Ghosts sold in the last five years, six fetched over a million dollars.)21

The original 1907 Rolls-Royce, with its polished aluminum body and precisely tailored engine and drivetrain, ran so quietly that it earned the name “Silver Ghost.” Note the spare wheel to make fixing a flat tire easy.

It was simple for salesmen to awe reporters and customers. They would place a coin balanced on edge—or a brimming martini—atop the Greek-portico radiator and invite the potential buyer to put the gearshift in neutral and accelerate the massive engine to full power. The balanced coin would not fall over; the martini would show not a ripple; the only sound was an intense, exhilarating purr.

The superb performance and reliability were designed into Rolls-Royces through how they were made. Each Silver Ghost was manufactured as a bespoke, unique vehicle, meticulously crafted by a dedicated team led by Henry Royce, the partner responsible for engineering. The experts assembling the car were armed, according to the book The Perfectionists, with “their loupes on lanyards, their slide rules, micrometers, calipers, verniers, and pressure gauges5.” Charles Rolls--the partner who handled marketing--told a reporter:

To produce the most perfect cars you must have the most perfect workmen, and having got these workmen, it is then our aim to educate them so that each man in these works can do his particular work better than anyone else in the world6.Peak output from the Rolls-Royce factory, from 1908 on, was two cars a day.

Henry Ford started manufacturing Model T’s—also in 1908—with the opposite goal. In order to build a car so cheap that his own factory workers could afford it, he abandoned construction by craftsmen and bet everything on a revolutionary substitute—the assembly line. His strategy came from a philosophy of precision and maintainability that was the reverse of the Rolls-Royce model.

At the Rolls-Royce factory, the highly skilled workers used files to minutely adjust every part to fit perfectly in the car they were working on. At the Ford factory, files were forbidden on the assembly line because anyone using a file to improve a part would slow or stop the line. The parts would arrive at each station perfect enough so that no micro-adjustments were needed. The worker’s job was limited to assembly, usually of just a small portion of the car—and his moderate pay reflected the modest skill required. Thanks to the resulting efficiency, a finished Model T came off the line every three minutes.

The whole process depended on the manufacture of truly interchangeable parts. That was where Ford put his obsession with precision. The specialized machine tools upstream of the assembly line had to make provably identical parts, which depended on extremely accurate measure—finer than one ten-thousandth of an inch.

Built in 1913, Ford’s 100-acre factory in Highland Park, Michigan, was the largest in the world and the first to employ a moving assembly line. By 1924 it was producing two million Model T’s a year. This photo from 1915 shows the chassis assembly line at the point where the pre-assembled dashboards were mounted and hooked up to the engine. The chain-driven assembly line reduced the man hours it took to build a Model T from twelve and a half hours to one and a half hours.

The two approaches to precision deployed by Henry Royce and Henry Ford led to two versions of success. Rolls-Royce produced the best cars in the world—nearly 8,000 of them in 20 years. In the same 20 years, Ford made the most popular cars—over 15 million. Royce hired and trained the world’s best workmen; Ford hired and unleashed the most innovative production engineers. Historian David Hounshell writes:

Ford had attracted to his factory a core of perhaps a dozen or a dozen and half young, gifted mechanics, none of whom had developed set ways of doing things. Encouraged by Ford, this group carried out production experiments and worked out fresh ideas in gauging, fixture design, machine tool design and placement, factory layout, quality control, and materials handling.7By selling Silver Ghosts only to the rich, the former newsboy Henry Royce became wealthy himself. Henry Ford was born a farm boy in Michigan. By pricing his Model T’s to sell to the middle class and poor, he became the richest man in the world. When he died in 1947, he was worth about $200 billion in current value. With every year of the Model T’s production, he improved its quality and lowered its price. In 1908 a Model T cost $825; in 1916 it was $345, and in 1925 down to $260. (The equivalent decline these days would be from $28,000 to $4,600.)

At that time, nearly everyone lived and worked on farms or ranches and in small towns. Most of them were proudly self-reliant, skilled at repairing anything they owned. Ford knew that and designed for it. In his 1922 book My Life and Work, he wrote, “I believed… that it ought to be possible to have parts so simple and so inexpensive that the menace of expensive hand repair work would be entirely eliminated. The parts could be made so cheaply that it would be less expensive to buy new ones than to have the old ones repaired.”19 The car had only 100 different parts, and they remained standard from the first Model T to the last, from 1908 to 1927. Every junked car was a trove of reusable parts.

Ford built the car to be so robust you could drive it anywhere and so simple and transformable that you were invited to adapt it to your own needs. Wikipedia’s “Model T” entry has this to say:

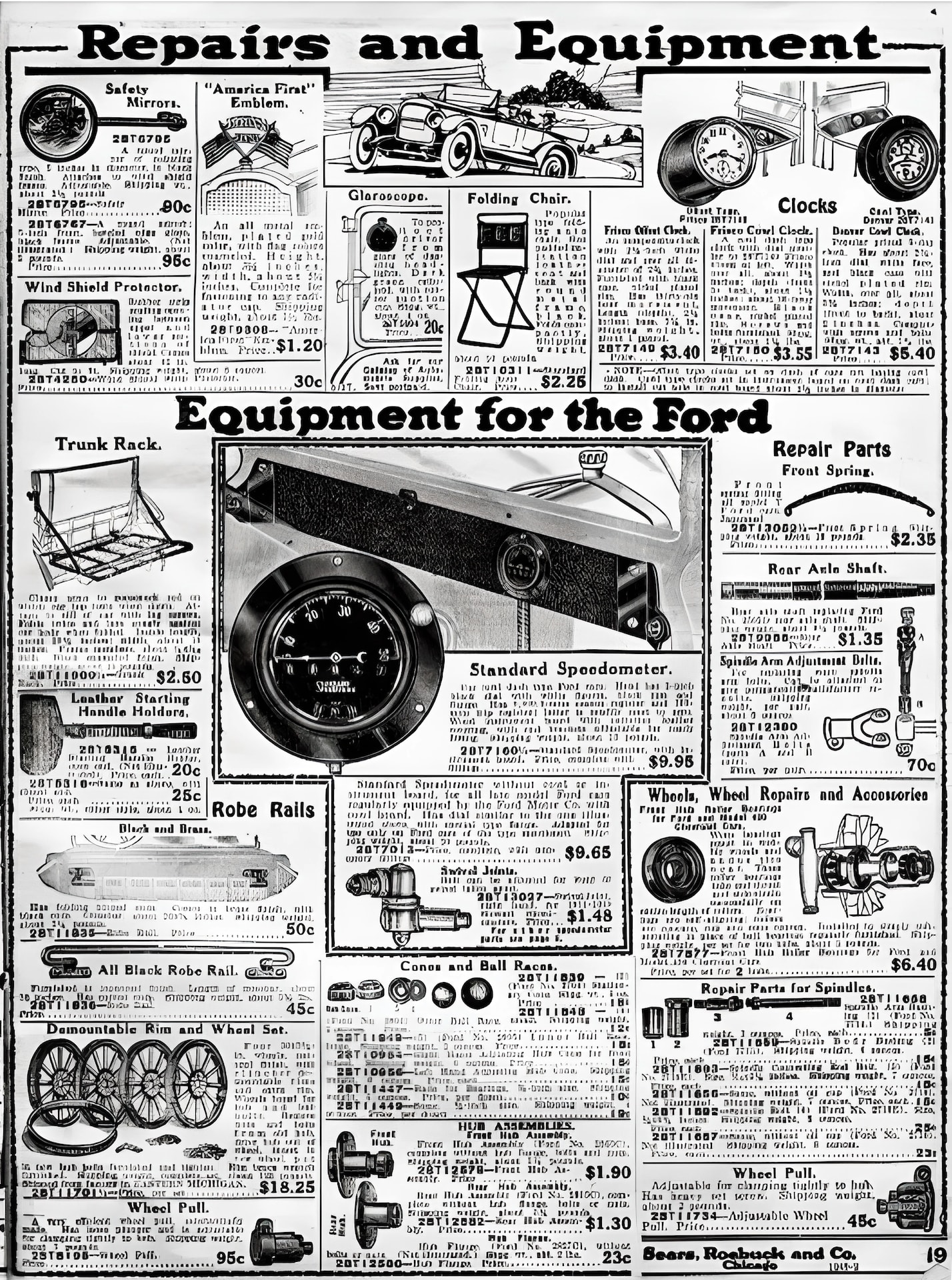

It could travel a rocky, muddy farm lane, cross a shallow stream, climb a steep hill, and be parked on the other side to have one of its wheels removed and a pulley fastened to the hub for a flat belt to drive a bucksaw, thresher, silo blower, conveyor for filling corn cribs or haylofts, baler, water pump, electrical generator, and many other applications.The huge aftermarket for Model-T add-ons and parts filled pages of the Sears Roebuck catalog and the shelves of specialty shops. Conversion kits proliferated for Model T-based tractors, trucks, taxis, rail cars, snowmobiles, boats, and even airplanes.

In 1915 auto dealer Ned Land adapted his Model T with tractor rear wheels to disk and seed his fields in north Texas.

1926. The Snowmobile Company of Rochester, New Hampshire, sold a popular conversion kit “Distributed Through Ford Agents” for the Model T. The kit was patented in 1917.

The 1919 Sears Roebuck mail-order catalog offered many pages of parts, embellishments, and tools for Model T owners.

This shop circa 1921 was dedicated solely to accessories and parts for the Model T. Visible are tire pumps, jacks, accessory brakes, side lights, and custom steering wheels (including the “fat man” wheel that could be slid upward on the steering column for easier entry.)

In a revered 1936 New Yorker essay titled “Farewell to Model T,” E. B. White wrote:

When you bought a Ford, you figured you had a start—a vibrant, spirited framework to which could be screwed an almost limitless assortment of decorative and functional hardware…. You bought a Ruby Safety Reflector for the rear… a fan belt guide to keep the belt from slipping off the pulley… a radiator compound to stop leaks… special oil to prevent chattering… a tool box which you bolted to the running board, a sun visor, a steering column brace… and a set of emergency containers for gas, oil, and water…. Owners… invented gadgets to meet special needs. I myself drove my car directly from the agency to the blacksmith’s and had the smith affix two enormous iron brackets to the port running board to support an army trunk…. Everybody carried a Jiffy patching set, with a nutmeg grater to roughen the tube before the goo was spread on. Everybody was capable of putting on a patch, expected to have to, and did have to.8(Those days are gone. Most drivers in developed countries don’t know how to change a car’s tire anymore, much less how to patch an inner tube. On one-third of new cars, there’s no spare tire at all.)

The writer E.B. White and his wife Katherine in a 1923 Model T in 1940. White drove his first Model T across America in 1922, when it was a hero’s journey to undertake. He was 23.

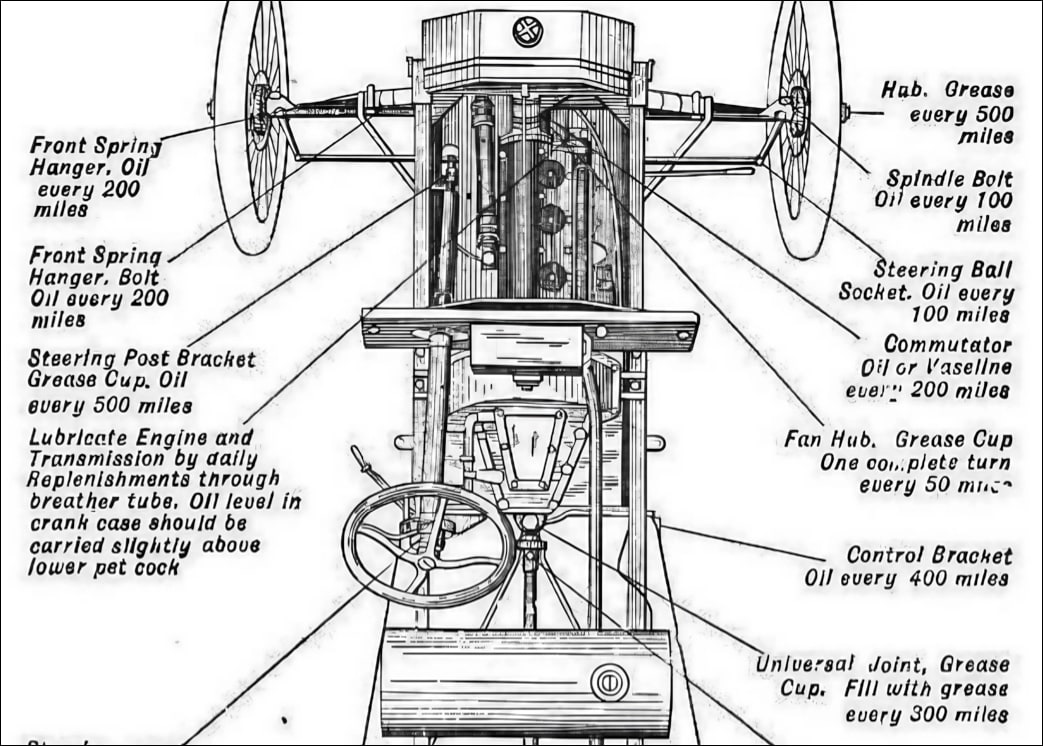

It wasn’t just the tires. Because the Model T had a simple, cheap “splash” lubrication system, its level had to be kept just right, and since there was no oil filter or pump, the oil would get dirty quickly and need replacement. Likewise, the simple, cheap “thermosiphon” water cooling system had no pump or thermostat, so the resulting slow flow easily collected dirt, rust, or air bubbles and clogged the radiator. The Model T’s low-compression engine used low-octane gasoline and that led to carbon build-up on the valves and pistons. Staying ahead of those hidden problems took close vigilance.

The owner had to learn certain skills to keep the car running. You had to know what to do when it wouldn’t start no matter how hard you cranked it. The problem was almost certainly the ignition or the fuel. To check the ignition, you would have someone else crank the engine while you found out if electricity was getting to all four sparkplugs. To avoid getting shocked, you would use a wood-handled screwdriver, touching its end to the engine block and leaning it close to each sparkplug. A nice fat spark at all four sparkplugs would impress bystanders and tell you the ignition was okay, so it must be a fuel problem. You would start at the gas tank (empty?) and its vent (blocked?), then—groan—the carburetor. You would examine the spray needle setting, the choke valve, the drain valve—and so on.

When the engine started knocking, an experienced driver could tell from the sound if it was caused by carbon build-up, a loose piston, a connecting rod, a main bearing, or a piston pin. The guilty cylinder could then be identified with a variation of the wood-handled screwdriver trick. With the engine idling, the screwdriver could be used to short the engine block to the exposed end of each sparkplug to make its cylinder cease firing. When the knocking went silent, that was the problem cylinder.20

There were so many Model T’s, the specialized knowledge needed to keep them running became common knowledge.

Your Model T had 24 lubrication points that needed periodic servicing. If you didn’t fill the grease cups and apply a grease gun to the fittings, your car would soon wear out as the moving parts turned into grinding parts. Often the grease would get so dirty on America’s dusty, muddy roads that it would need complete replacement

Model T owners learned mechanic skills. This group may have stopped for a rest when they felt like it, or the Model T may have stopped when it felt like it. In either case, the four-cylinder, 20-horsepower engine evidently needed attention. Note the spare tire (not wheel).

Anyone who tried to customize a Silver Ghost would probably screw up its tightly integrated perfection, so no one did. Every Model T, on the other hand, required some customization just to function well, and that inspired owners to devise all manner of new features and functions. A Rolls-Royce, impressive as it was, had just one use. When Ford put the power to make changes in the hands of his millions of customers, the Model T’s evolved rapidly in all directions and were put to countless uses.

Royce served his customers well by crafting a vehicle that they could trust as totally reliable. It would never embarrass them by not running beautifully. Ford did a different favor for his customers. He designed a car so cheap that anyone could buy it and so uncomplicated that anyone could learn to do the maintenance it required. Once the customers took that on, they discovered that the power to maintain is the power to improve. Model T’s inspired user creativity at a massive scale worldwide.

Decades later, something similar occurred when user inventiveness was unleashed by personal computers, then by cell phones, and then by the World Wide Web. As each of those took off exponentially, the result was explosive. Model T’s showed how that could happen.