Digression 4 - SUSTAINMENT - How Poor Maintenance Loses Wars - 1973, Israel Maintains

IIS THERE SUCH A THING as “maintenance mind?” If so, what are its features, and what is its underlying character? What hinders it? Can it be cultivated? Can it be institutionalized? This digression about the role of maintenance in two wars may have some clues.

War one—1973. On the 6th of October that year, Israel was attacked by Egypt and Syria simultaneously. The conflict was variously named the Yom Kippur War, the Ramadan War, and—the non-sectarian option—the October War.

The assault by Egypt and Syria arose directly from what had happened six years before in the Six Days War of 1967. After its crushing victory over Egypt in that war, Israel took possession of the Sinai Peninsula and fortified its new border with Egypt on the eastern bank of the Suez Canal with elaborate defenses called the Bar Lev Line. Behind a continuous berm of sand and concrete 75 feet high, the Line stretched 93 miles long and 19 miles deep, comprising three layers of roads connecting 22 forts, 35 strongpoints, and 11 strongholds. Supporting the Bar Lev Line from nearby was an armored division of 8,000 soldiers and 350 tanks. The defenders knew they could count on at least 48 hours of warning before an attack, and it would take any attacker another 48 hours to breach the high berm by the Canal with explosives or tractors—plenty of time for additional Israeli armored divisions to arrive.

Egypt’s surprise attack across the Suez Canal on October 6 nullified all that. It took only an hour for forty engineer battalions using water cannons to blast through the sand berms. In the opening phase of the attack, 32,000 Egyptian troops, followed by 200 tanks, crossed the Canal, first in boats and ferries, then on 20 floating bridges. Israel’s vaunted Air Force could not stop the crossing because of an overwhelming barrage from Soviet-made Surface-to-Air Missiles on the Egyptian side of the Canal. Also, to divide Israel’s forces, Egypt’s offensive was synchronized with a massive tank attack by Syria in the north to seize Israel’s Golan Heights.

October 6, 1973. That day of triumph and glory for Egypt is depicted in a circular mural at a military museum* near Cairo called “The 6th of October Panorama.” (There’s a reason it’s not called “The Ramadan War Museum.”) This section of the panorama shows two of Egypt’s 20 floating bridges across the Suez Canal. In the foreground, Israel’s supposedly impregnable sand berms are being blasted away with water cannons. The stunning success of Egypt’s surprise attack was the product of six years of meticulous planning and rehearsal.

By October 8, Egypt had another 60,000 troops and 600 tanks across the Canal, setting up long-planned defensive positions. When Israel hastily counter-attacked with 640 tanks in three armored divisions, they were met by Egyptian infantry ready for them, armed with Soviet wire-guided anti-tank missiles and rocket-propelled grenades. At the end of a bloody day, 400 of Israel’s tanks were destroyed, the counter-attack had failed, and Egypt controlled the entire former Bar Lev Line. Israel was in shock.

Egypt’s triumph was a retaliation six years in the making. In 1967, Egypt responded to the humiliation of its defeat in the Six Days War by devising a plan to recapture the Sinai. The government invited assistance from the Soviet Union. By the early 1970s, Egypt was fully armed with Soviet tanks, fighter jets, surface-to-air missiles, anti-tank missiles, and as many as 20,000 military trainers and specialists.

The invasion across the Canal was planned in elaborate detail. Half the engineers in Egypt—some 15,000, deployed in 40 combat engineer battalions—were tasked with designing the crossing and carrying it out. When experiments showed how long it would take to blow up or bulldoze through the high sand berms of the Bar Lev Line, a junior officer named Baki Zaki Yousef came up with the idea of using water cannons. Every detail of making the crossing and establishing multiple bridgeheads on the other side was rehearsed exhaustively for years before the attack. Analyst James Powell writes:

Squads and platoons trained on mockups of Bar-Lev Line fortifications. “Tank-hunting teams” of infantry familiarized themselves with Sagger wire-guided antitank missiles repeatedly over the course of several months, firing up to 25 per day on special ranges. The dissemination of explicit, detailed instructions enabled soldiers across the armed forces to hone the specific skills that would be required of them during the anticipated assault.1It paid off. Military historians regard Egypt’s “Operation Bar” offensive as a masterpiece of deception, strategy, training, coordination, and logistics.

Then it went sour. On October 14, Egypt launched 1,000 tanks in an immense but disorganized attack toward the Sinai passes twenty miles away. It was a catastrophe. The following day, Israel launched a counter-attack with three divisions across the Canal into Egypt, threatening cities north and south of their bridgehead. The Israeli forces destroyed enough of Egypt’s surface-to-air missile sites on the west side of the Canal to regain air dominance. Egypt’s spectacular victory had capsized into defeat. What happened?

One answer is spelled out in a 2019 paper titled “Taking a Look under the Hood: The October War and What Maintenance Approaches Reveal about Military Operations,” by US Army Colonel James Powell. I’m drawing on his paper and other analyses to see what the conduct on both sides of the October War might reveal about “maintenance mind”--because apparently the Israeli troops had it and the Egyptian troops didn’t, and it turned out to be pivotal.

In the Golan Heights battles against Syria, as in the Sinai Peninsula against Egypt, Israeli tank crews and Ordnance technicians worked 24 hours a day to get their battle-damaged Centurion tanks back in combat immediately. On October 10, 1973, the group in the foreground is fixing the idler wheel that maintains the track tension on a tank. The mobile crane in the back is swapping out a tank’s diesel engine. Neither the Syrian nor Egyptian armies recovered and repaired their own tanks. According to one report on the Golan Heights battle, “just 177 Israeli tanks resisted the concerted offensive of 1,400 Syrian tanks over a period of 81 hours without reinforcement and with hardly any sleep or respite under the incessant artillery bombardment.”[1] With the arrival of Israeli reinforcements, the Syrian forces were swept from the Golan Heights, leaving 867 disabled tanks behind—many of which were repaired and put to use by Israel.

Israeli tanks counter-attack across the Suez Canal into Egypt, October 15, 1973. Israel’s upgraded British Centurion tanks like this one were considered evenly matched with Egypt’s Soviet T-55 tanks, but their crews were not. Israeli tank crews had the skills and tools to maintain and repair their tank, and the Egyptian crews didn’t. Most of Egypt’s tank repair was done in depots far from the fighting by foreigners such as Cubans.

The shocking statistic is that, of the 840 tanks Israel lost to battle damage in the war with Egypt, fully half were recovered, repaired, and returned to the fight. Colonel Powell credits the Israeli military with

a mindset that naturally viewed damaged tanks as soon-to-be-repaired tanks, rather than the irredeemable flotsam of battle. The fact that [Israeli] commanders thought in these terms gave purpose and direction to the maintenance-related technical and tactical skill their crews possessed.2 Each tank crew of four had the tools and ability to do minor repairs, and Ordnance teams in the rear were equipped to repair major damage and return disabled tanks to action quickly. Division commander General Bren Adan was moved to devise a tactical innovation in the thick of the fighting after he noticed that some of his tanks were inexplicably moving to the rear. When he learned they were bringing wounded crew members and other problems back to be dealt with, he established a “checkpoint” just behind the front to provide fuel, ammunition, medics, and ordnance technicians. Adan recounts in his memoir:

Our procedure was to halt a tank at the checkpoint, and the crew would report their problems. The officers there would see to the evacuation of the wounded, then combine crews from two tanks that had been hit. After giving them a "pep talk," they would send the men back to the front. Malfunctioning tanks would either be repaired on the spot by mechanics or the crew given another tank so they could get back to the battlefield. There was considerable improvisation at the checkpoint, and many tanks and crews were able to be sent back into battle quickly.3 In Colonel Powell’s “Under the Hood” paper, he proposes that innovation like Adan’s reflects “the productive relationship between Israel’s military and scientific communities and the country’s underlying culture of improvisation.” He adds:

In the Israeli way of war, skilled tactical leaders and technically-proficient weapon crews were top commodities. The challenges of maneuver warfare were best handled by officers and men accustomed to exercising initiative in the midst of fast-paced, decentralized operations. What is more, against a numerically superior foe, these qualities applied also to the realm of maintenance in the sense that every armored vehicle counted.4

Israeli troops in an armored personnel carrier advance past one of Egypt’s Soviet T-55 tanks abandoned on the battlefield. A little smaller than Israel’s Centurion tanks, the T-55s presented a smaller target, but inside, they were cramped for the crew of four. There is no evidence that any of the damaged or abandoned T-55s were recovered and repaired by Egyptian forces.

Most of Israel’s main battle tanks in the October War were British Centurions that had been upgraded. Egypt’s enormous inventory of tanks was made up largely of Soviet T-55s. The Soviet Union had designed the tank on the same principles as their AK-47 assault rifle—simple, rugged, reliable, and cheap to manufacture. Between 1952 and 1977, nearly 100,000 T-55s were produced and used in combat worldwide—more than any other tank in history. Its simplicity and reliability should have made the T-55 easy for Egyptian troops to maintain and repair, but it didn’t work out that way, for reasons that had nothing to do with the tank.

A trait that the Egyptian army and its Soviet trainers had in common was that they discouraged soldiers below the level of general from taking initiative of any kind. The job of everyone in the military, especially the junior officers, was to follow orders without deviation. “Soviet commanders considered ‘improvisation’ a pejorative term,” writes Colonel Powell, “since it seemed to indicate, above all, a lack of preparation.”5

Family life in Egypt’s villages has the same structure. The patriarch decides nearly everything for everyone in his extended family. They are kept in line with the powerful culture of shame common throughout Arab countries. In a book titled Armies of Sand, author Kenneth Pollack states that: “Because shaming is the primary instrument by which Arab society enforces conformity, and because shame is considered an unbearable punishment, “worry about external dignity is (the Arab’s) continual concern.”6 Pollack adds:

Fear of dishonor also contributes to tendencies toward secrecy and compartmentalization of knowledge. Shame attaches only when the sin becomes public…. In order to conceal mistakes that would result in shame, features of Arab culture encourage the individual to exaggerate, lie, and/or remain secretive.7Norvell de Atkine, a retired US Army colonel who got his graduate degree in Arab studies and spent eight years training soldiers in Egypt, Lebanon, and Jorden, has this account:

Arabs husband information and hold it especially tightly…. Having learned to perform some complicated procedure, an Arab technician knows that he is invaluable so long as he is the only one in a unit to have that knowledge; once he dispenses it to others he no longer is the only font of knowledge and his power dissipates…. On one occasion, an American mobile training team working with armor in Egypt at long last received the operators’ manuals that had laboriously been translated into Arabic. The American trainers took the newly minted manuals straight to the tank park and distributed them to the tank crews. Right behind them, the company commander… promptly collected the manuals from those crews…. He did not want enlisted men to have an independent source of knowledge. Being the only person who could explain the fire control instrumentation or bore sight artillery weapons brought prestige and attention.8The avoidance of public dishonor was partially responsible for the chaos of Egypt’s massive tank attack on October 14, which cost Egypt the loss of 265 tanks to Israel’s 40. (Israel quickly repaired all but six of that 40.) Up to that day, every action of Egypt’s forces had been tightly scripted and rehearsed. The moment they went off script, they floundered. Junior officers had no training in taking initiative in rapid-maneuver warfare, and the dread of making a mistake hobbled them. “In Arab society,” writes Pollock, “to do something wrong generally is much worse than to do nothing at all.”9 So Egypt’s tank formations attacked whatever was directly in front of them and were shredded by Israel’s fast, impromptu maneuvering.

When things began to go badly on the battlefield, Egypt’s generals were unable to know what was happening and redirect it because the officers in the field could not bear to report bad news and instead proclaimed fictional successes. “Starting on October 14,” writes Pollock, “the combat reports… coming in from tactical commanders spiraled off into fantasy.”10 Egypt’s defeat that day was the turning point of the war.

Most damaging of all for maintenance in Arab militaries is the officers’ disdain for manual labor and their caste-like distance from enlisted men. By one scholarly account, “There is a common and very deep-seated feeling that manual or rural forms of work mean drudgery and nothing more; that furthermore, there is an element of degradation in them, so that they must be avoided by all and any means.”11 De Atkine reports:

Officers refuse to get their hands dirty and prefer to ignore the more practical aspects of their subject matter, believing this below their social station. A dramatic example of this occurred during the Gulf War when a severe windstorm blew down the tents of Iraqi officer prisoners of war. For three days they stayed in the wind and rain rather than be observed by enlisted prisoners in a nearby camp working with their hands.12“Most Arab armies treat enlisted soldiers like sub-humans,” writes De Atkine. Consequently, “The young draftees who make up the vast bulk of the Egyptian army hate military service for good reason and will do almost anything, including self-mutilation, to avoid it.” A vital missing element, De Atkine argues, is that “Most of the Arab world either has no NCO corps or it is non-functional.” NCOs are non-commissioned officers—the sergeants. In effective military forces, they provide the bridge of trust between officers and enlisted troops, they conduct most of the training, and they oversee maintenance and repair work. Typically an NCO is the most experienced soldier in a unit and is respected accordingly. De Atkine observes, “Without the cohesion supplied by NCOs, units tend to disintegrate in the stress of combat.”13

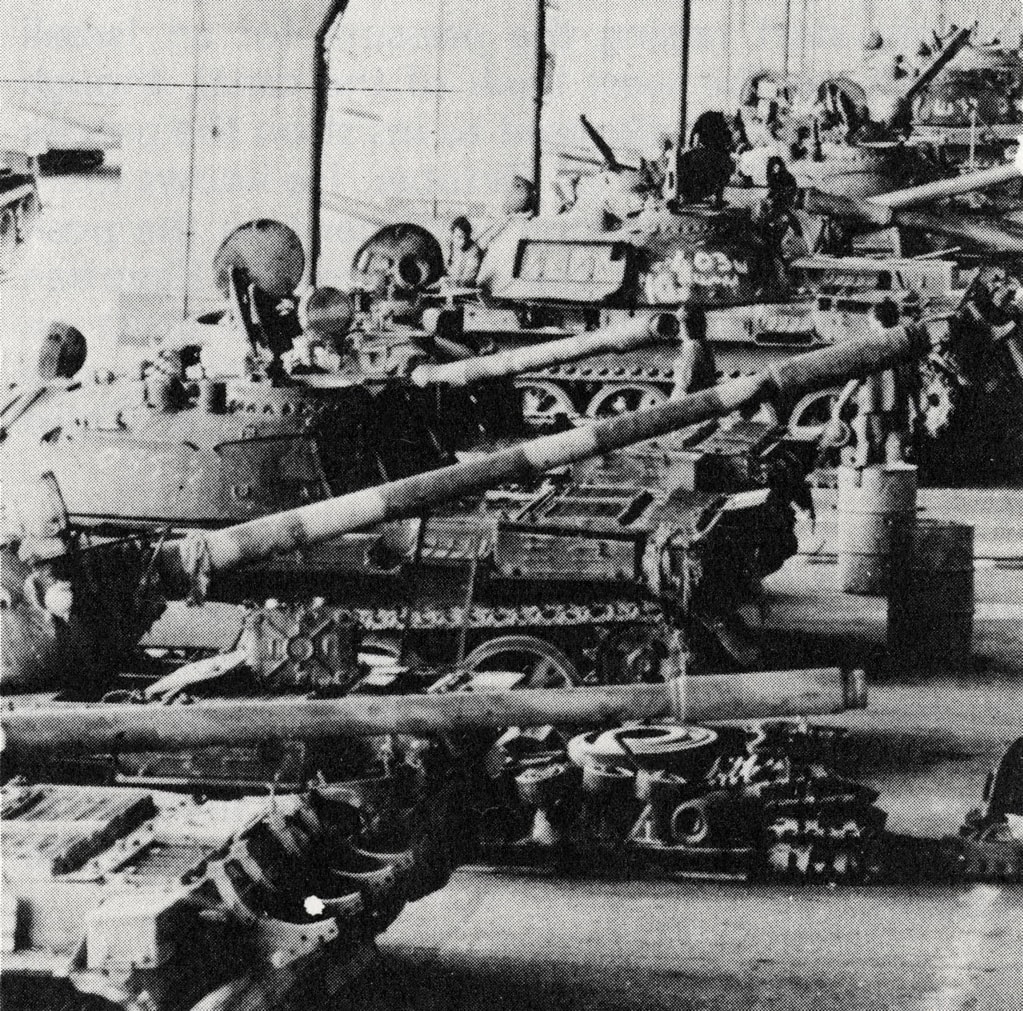

At an Israeli Ordnance depot, Soviet T-55 tanks abandoned on the battlefield by Egyptian and Syrian soldiers are repaired and refitted for use as Israeli tanks.

Desert warfare is maintenance-intensive. A US Army manual warns that “sand mixed with oil forms an abrasive paste.” American tank crews fighting in desert conditions are required to constantly inspect and replace all oil, fuel, and air filters, check lube fittings and Teflon bearings, and change the engine oil frequently.14 Powell points out that in 1973:

Despite their reputed ruggedness, the Soviet-made tanks in Egypt’s arsenal were not immune to the effects of inadequate maintenance under conditions of sustained combat—particularly in the desert. Ten days into the war, about 80 percent had broken down.15 The Egyptian attitude toward maintenance was so “abysmal,” reports Pollock in Arabs at War, that “crews abandoned vehicles on the field of battle because of relatively minor problems.”16 In Powell’s account, this presented an opportunity for Israel’s Ordnance teams. They

recovered and went on to employ about 300 repairable Arab tanks during the conflict... Familiar enough with their own equipment, Israeli soldiers could transfer that knowledge and apply it to the maintenance and operation of analogous weapon systems—even ones that began the war on the opposite side17.Some of Egypt’s T-55 tanks became part of Israel’s counter-offensive across the Suez Canal.

The maintenance disparity I’ve described here was duplicated in Israel’s victory over Syria in the Golan Heights and its air war with Egypt above the Suez Canal. It was a different story, however, with Egypt’s engineer battalions that bridged the Canal. Israel’s Air Force, reports Powell, “targeted pontoon bridges as a way of disrupting the crossing, but they soon found that Egyptian engineers repaired the damage so quickly as to render bombing and strafing runs nearly fruitless.”18 It should also be noted that throughout Egypt’s forces, Pollock acknowledges, “Unit cohesion and personal bravery… were high points for the Egyptians during the October War.”19

Arab armies often excel in handling logistics operations. The most impressive in the history of Arab nations was Egypt’s assault across the Suez Canal that overwhelmed Israeli defenses on the 6th of October, 1973. The soldier on the Soviet T-55 tank is brandishing a Soviet AK-47 assault rifle.

The fighting ended when a cease-fire was declared on October 25th, brokered by the United Nations, the United States, and the Soviet Union. Israel had once again prevailed on the battlefield, but you would never know it from how the two countries behaved after the war. Egypt celebrated the first four days of the war as a famous victory over Israel and forgot the rest. Israel acted as if they had lost the war. Historian Simon Dunstan describes the reaction:

The Israeli people were staggered by the early successes of the Arab armies that smashed the myth of Israel Defense Force invincibility, and the scale of their casualties was beyond comprehension….. That anger was reflected in the ballot box when the Labour Party that had held office for almost 30 years was voted out of office, ending the political careers of Prime Minister Golda Meir and Defense Minister Moshe Dayan…. They were replaced by the right-wing Likud government of Menachem Begin in 1977…. Israel's faith in her leaders, both political and military, was shaken, leading to the factionalised and polarised society that exists today.20Geopolitically, the war’s outcome was treated as a draw. It led directly to the Egypt-Israel Peace Treaty of 1979, which normalized relations between the two countries.

Every major military in the world has studied the October War to see how its lessons might apply to them. Colonel Powell’s paper draws attention to what China’s military analysts learned. They wrote in 2005:

In the Middle East War of 1973 . . . it was only when the Israeli army enhanced its technical support . . . that 80 percent of the damaged tanks in the war could be recovered and sent back to the battlefields. . . . The equipment support ability of the Israelis . . . contributed a great deal to the reversal of their disadvantageous posture and changed the process and outcome of the war.21Powell himself concludes:

An understanding of how a military regards and conducts maintenance… sheds light on the extent to which it will be able to improvise in wartime. Maintenance proficiency serves as an indicator for how fast and how frequent new techniques can be developed and implemented and whether the expertise exists to apply them widely across the force as it fights.22In other words, maintenance prowess is core to rapid adaptivity under duress. Israel had institutionalized it. Egypt never tried, apparently for reasons embedded culture-deep.

_____________

(This is the 1st of 3 segments in the SUSTAINMENT Digression. “Sustainment - the Concept” is the next segment, followed by “2022, Ukraine Maintains.”)