Digression 2: From MANUALS to YOUTUBE (with a detour) - Two Assault Rifles

SOME OF THE MOST VALUED MANUALS focus on known weaknesses of the device in question. John Hall’s musket manual did that. So did John Muir’s VW manual. This digression-within-a-digression examines what was behind the most famous of all manuals dedicated solely to maintaining a flawed tool. It emerged from the Vietnam War and is one of the harshest maintenance dramas in history.

In the early years of the war—the mid-1960s—the North Vietnamese outgunned US forces on the ground. China had provided them with AK-47s—a cheap, highly effective firearm referred to as an "assault rifle"—which means a gun that can switch from semi-automatic (bang bang bang) to fully automatic (braaaaaaaapp). The US responded by fielding its own assault rifle— a brand new, highly sophisticated weapon called the M16. It was extremely accurate, even out to 500 meters. It was light, with a distinctive carrying handle on top. The butt was in line with the barrel, so it did not “climb” when fired on full auto. It was ergonomically brilliant--perfectly balanced and smooth-operating, with every control in easy, intuitive reach.

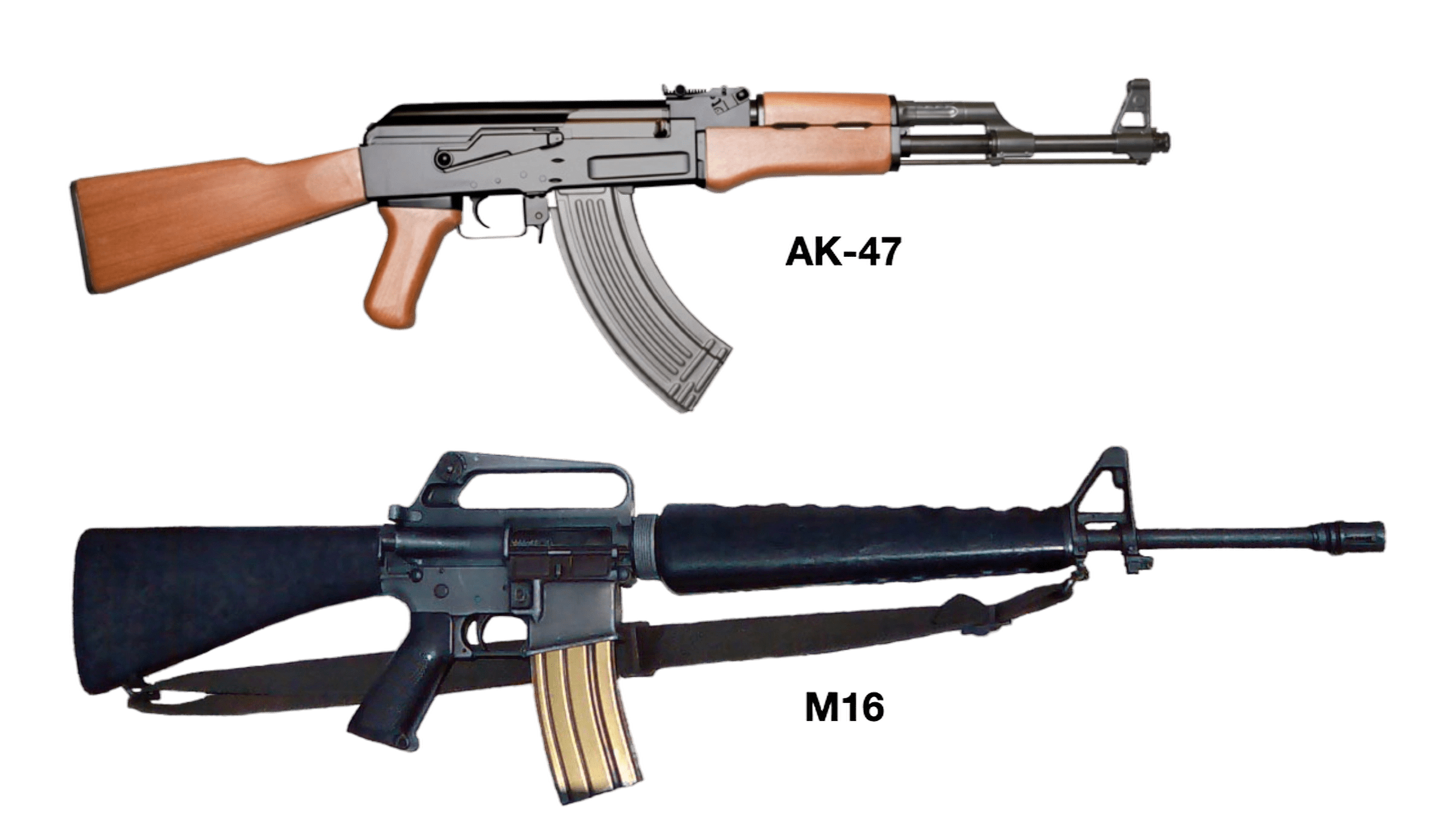

The maintenance-friendly AK-47 - designed in Russia in 1947-49. Length 34 inches. Weight 10.5 pounds with fully loaded magazine (30 rounds). 73 parts. Note the cleaning rod mounted under the barrel, in handy reach.

The maintenance-hostile M16 - designed in the US in 1957, originally as ArmaLite AR-15. Length 39 inches. Weight 7.9 pounds with fully loaded magazine (30 rounds). 144 parts.

Old systems fail in familiar and prepared-for ways. New systems fail in unexpected and unprepared-for ways.

In the jungles of Vietnam, the M16 had a definitively fatal flaw: it was fatal to its users. The gun routinely jammed in the midst of a firefight, leaving the rifleman defenseless. In May 1967, one Marine wrote to his family: "We left with 250 men in our company and came back with 107. We left with 72 men in our platoon and came back with 19. Believe it or not, you know what killed most of us? Our own rifle. We were all issued this new rifle, the M16. Practically every one of our dead was found with his rifle torn down next to him where he had been trying to fix it.”1

Outrage like his was delivered directly from the soldiers to their parents and hometown newspapers and thence to their representatives in Congress. When the issue became a public scandal, senior leaders of the Army and Marines repeatedly declared that the M16 was a great weapon with no problems at all. The enemy knew better. According to one report, “The only things that were left by the enemy after they had stripped the dead of our side were the rifles, which they considered worthless.”2 (The US military’s pattern of denying problems and exaggerating successes continued for nine more years until it culminated in our total defeat in 1975.)

A subcommittee of the House Armed Services Committee conducted a formal investigation in 1967. What they found in Vietnam shocked them. In the 1st Infantry Division (15,000 soldiers), for example, the state of maintenance of the M16s was “indescribable,” according to one inspector. Kanemitsu Ito, a veteran of the Korean War, reported, “I have never seen such filthy, rusty, carboned, and corroded rifles, magazines, and ammunition. It is no wonder that these rifles will not function.”3 It turned out that the M16s, having been touted as “self-cleaning,” were being treated by some units as if they needed no maintenance. Cleaning kits and instruction weren’t even provided to many of the soldiers.

But most of the problems were in the M16 itself. The Congressional inspectors found that the ammunition had the wrong powder, which fouled the rifle’s mechanism. They found that the unchromed barrel and chamber led to corrosion that would cause the bullet casing to jam in the chamber. They found that the rifles would jam no matter how surgically clean they were. They found that the aluminum magazine carrying the bullets was so flimsy it was easily damaged, and the bullets wouldn’t feed. Forty percent of the magazines in the field were too broken to use. (The steel magazines of the AK-47, by contrast, were so sturdy they could be used as a hammer and bottle-opener.)

Viet Cong soldier with his robust AK-47 near Saigon in 1968.

A US Marine cleaning his M16 during the Battle of Hue, Feb. 1968. Even when perfectly cleaned, M16s were unreliable in 1968.

I take all this personally. I was a professional rifleman in the early 1960s, serving for two years as an infantry officer teaching basic training. Some of the recruits I helped train went on to fight in Vietnam. If I had stayed in the Army, I might well have wound up as Company Commander of a line unit there, with total responsibility for the lives of 200 men. Sending them into combat with an unreliable weapon would have felt like fratricide—the unintentional killing of comrades in arms.

There’s a famous series of combat photos from early in the Vietnam War whose full story is seldom told. They were taken at the end of April, 1967, in what was called “The Hill Fights” or “The First Battle of Khe Sanh.” One hundred fifty-five US Marines were killed, 425 wounded—the bloodiest battle of the war up to that point and the first in which American soldiers were armed solely with the new M16s. One Marine wounded in the battle limped to the rear using two hopelessly jammed M16s as crutches.27 Some of the most intense fighting was on Hill 881, a bunker complex manned by North Vietnamese. Embedded with the Marine attackers that afternoon was 22-year-old French photographer Catherine Leroy.

April 30, 1967. Hill 881. Navy Corpsman Vernon Wike treats the chest wound of Marine Lance Corporal William “Rock” Roldan, shot while he was trying to clear his jammed M16.

After listening to Roldan’s heartbeat slow to nothing, Wike reacts in agony.

The photographer recalled, “I heard someone yelling, ‘Corpsman, corpsman!’ And I saw this other Marine rushing to the wounded man, and he put his ear on the man’s heart. Then he looked up in total anguish.”28 The wounded man was Lance Corporal William Roldan, age 20. The Corpsman, Vernon Wike, age 19, knew him as “Rock.” Partway up Hill 881, Rolden’s M16 jammed. When he crouched to try to clear it, a North Vietnamese with an AK-47 in one of the bunkers shot him in the chest. In the 2007 book The Hill Fights, Corpsman Wike is quoted:

As soon as I reached him, I saw it was ‘Rock.’ We’d just met that morning. He told me he had less than sixty days left in-country. I put my hand on his chest. It slipped in all the blood. Then I found the entrance wound on his left side. I put a bandage on it. I was talking to Rock, but he was unconscious. I then put my head on his chest. I could hear his heart, but it was getting fainter. Then I found the exit wound and knew he’d been hit in the lungs. Then Rock died.28Two weeks later, in May 1967, Leroy’s photos were published in Life magazine and Paris-Match to great acclaim. Neither article made any mention of jammed M16s. That same week in May, the letter from a survivor of the Hill Fights was read aloud in Congress. It ended: “Practically every one of our dead was found with his rifle torn down next to him where he had been trying to fix it.” Thus began the Congressional investigation.

It takes a long time to make adjustments in a mass-manufactured complex tool. During the dangerous wait for better M16s, the Army decided to adjust the mind of the troops first. (Software fixes are quicker than hardware fixes.)

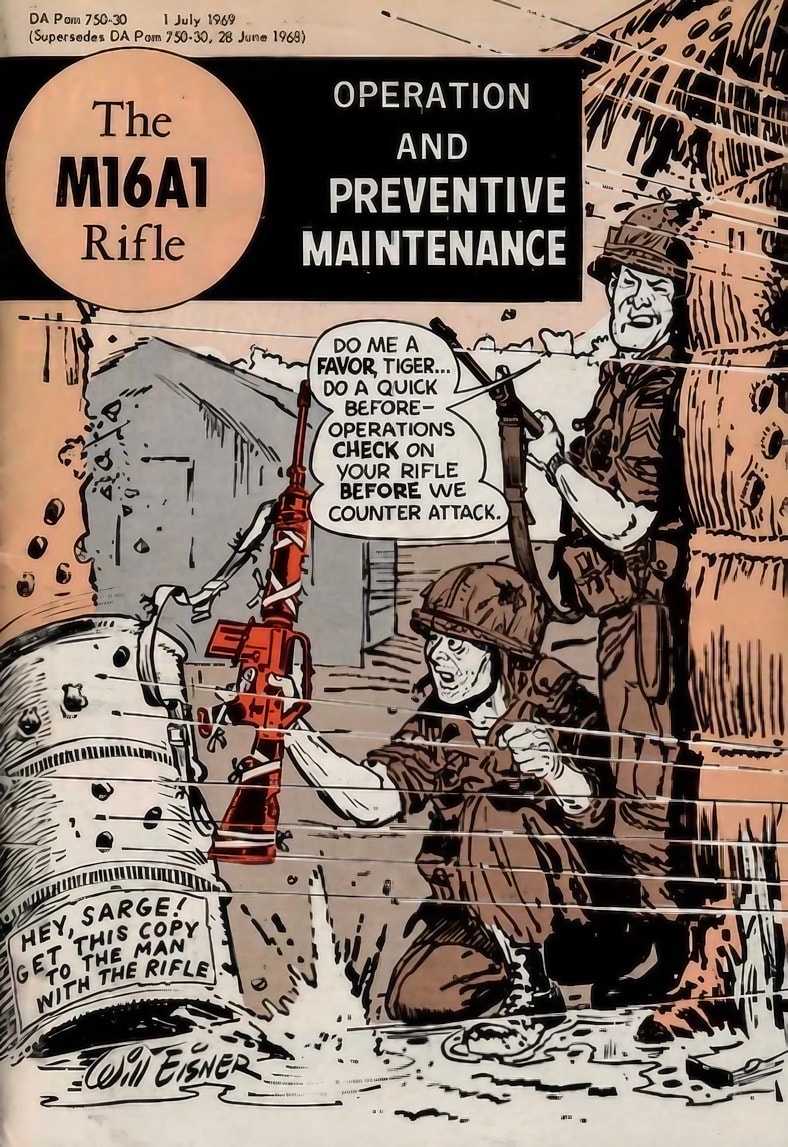

In the 1960s, the combat soldiers in Vietnam were all young males and nearly all avid readers of comic books. That explains why, in 1969, the US Government Printing Office printed countless copies of Pamphlet 750-30, titled The M16A1 Rifle: Operation and Preventive Maintenance. They were distributed to every soldier in Vietnam or on the way there.

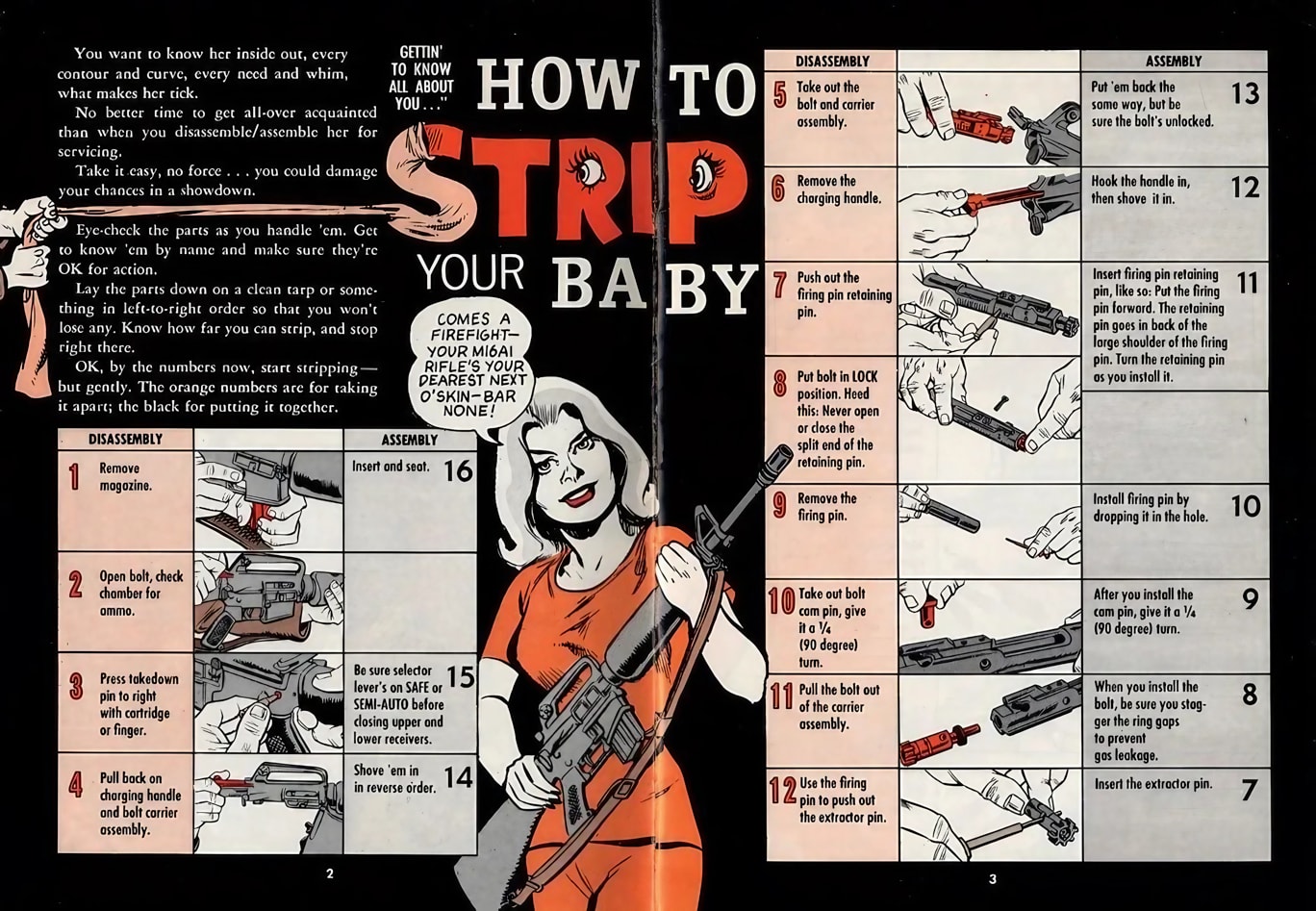

It was a jokey 32-page comic book drawn by the revered comic artist Will Eisner. Its first three pages, titled “How To Strip Your Baby,” illustrated the nineteen steps it took to disassemble the M16. The text began with flirty language: “You want to know her inside out, every contour and curve, every need and whim, what makes her tick.”

The M16 required assiduous maintenance to function at all, and its design made maintenance difficult. The famed cartoonist Will Eisner spent a month visiting troops in the field before writing and illustrating this comic book manual.

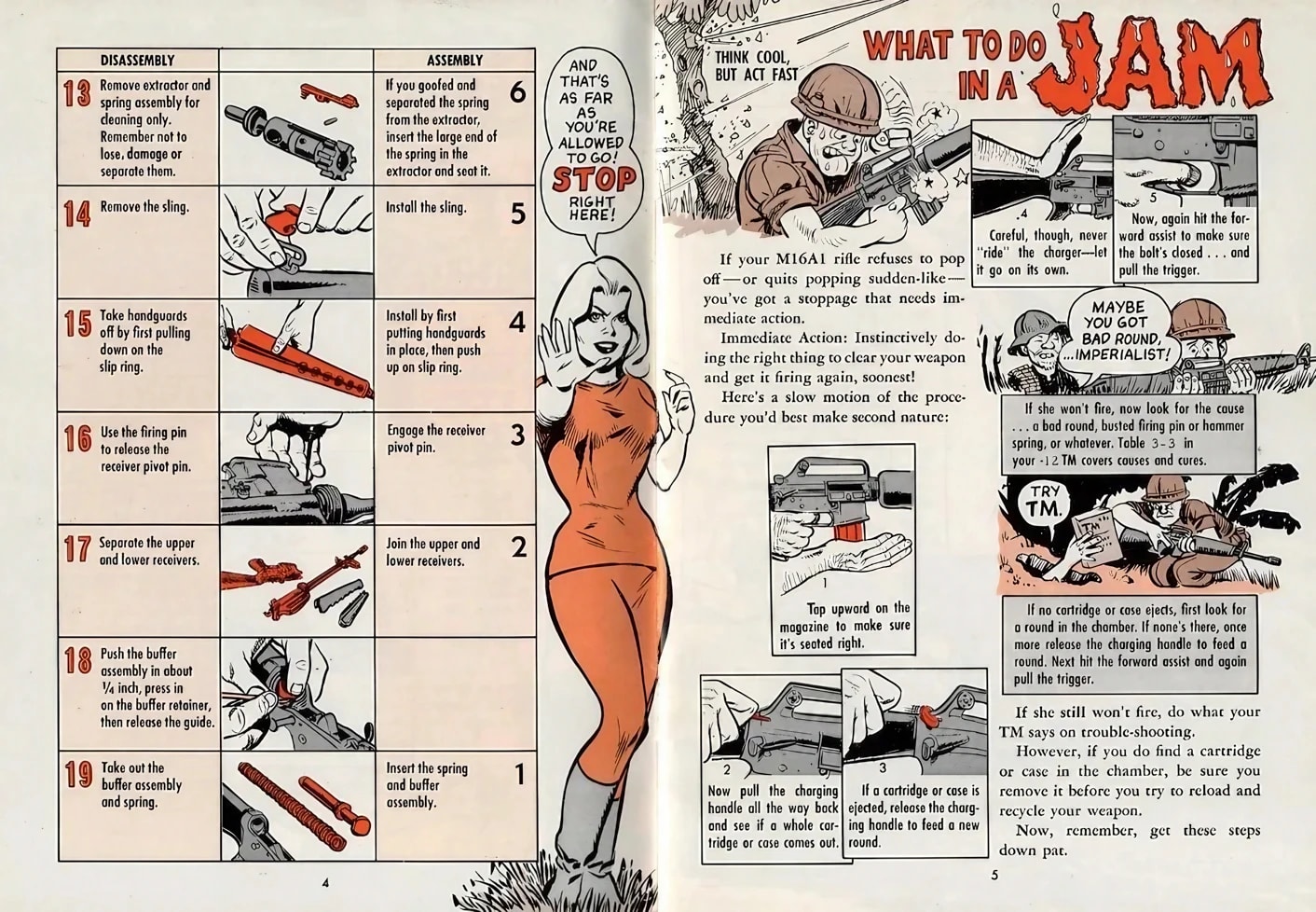

In the comic, the 19 steps of disassembly of the M16 are cleverly arranged as a caption-column to read down on the left, and then reassembly is guided by reading the caption-column on the right upwards. Unlike the AK-47, the M16 required intricate maintenance (and still does). Some vital details are easy to get wrong, such as inserting a certain small pin in its hole from the wrong side, guaranteeing the rifle will jam (Step 11.) If you attempt the final step of reassembly (Step 15) with the selector switch set to “Auto” instead of “Safe,” you will damage the parts. Eisner’s comic has a whole page on the crucial task of clearing a jammed rifle, but it does not deal with the most frequent cause of jamming: a cartridge stuck in the chamber. The only cure for that is to run a cleaning rod down the barrel and push it out.

A page titled “What To Do in a JAM,” addressed the M16’s most infamous weakness. It illustrated the five rapid steps of “the procedure you’d best make second-nature” to clear the jam. Several pages were dedicated to the delicate magazine—how to adjust the magazine catch, get cartridges in and out without bending anything, and disassemble the magazine for cleaning.

The soldiers were prohibited (“STOP right here!”) from disassembling the complex lower receiver; any problem with it had to be sent to specialists. No wonder: that mechanism had 31 parts, and nine of them were tiny springs poised to spring away and hide. The price of the beautifully smooth action of the M16 was having to forbid the user from inspecting and cleaning the parts that made it smooth.

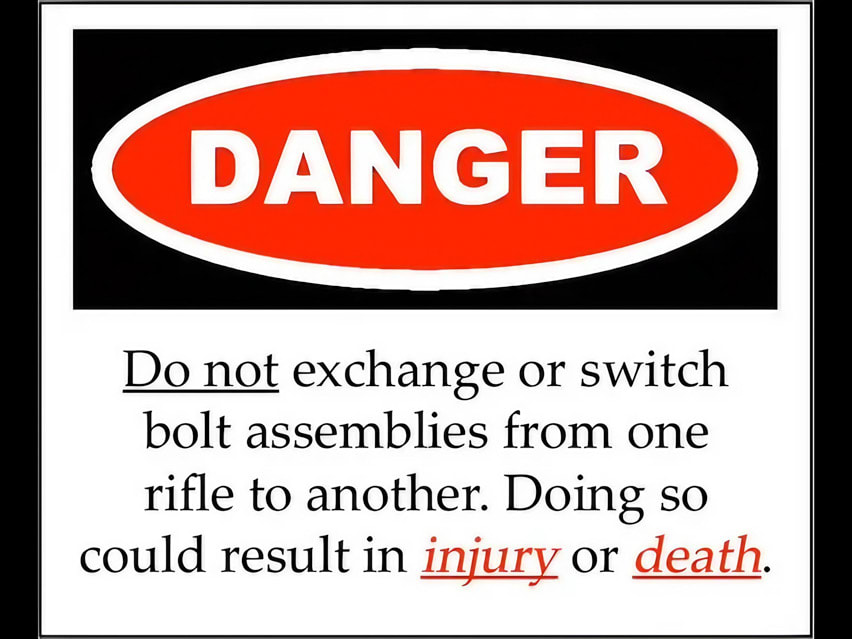

Field-stripping the M16 was a pain. There were fifteen disassembled components to keep track of, including four fiddly little pins that could easily be lost. A technical manual dryly explained that one of the smallest parts, the bolt cam pin, “must be installed or rifle will blow up while firing the first round. Doing so may result in injury, or death of, personnel.” The manual added, “Do not interchange bolt assemblies from one rifle to another. Doing so may result in injury, or death of, personnel.”4

So much for interchangeable parts. (The enemy’s AK-47s disassembled to just six components, all large, all interchangeable. And no mistake in reassembly could make the weapon blow up.)

A standard warning from instructors on disassembling and reassembling the M16 for cleaning. The rifle’s design reversed the usual benefit of precision manufacturing, that parts are thus interchangeable. In the M16, the parts were—and still are—so precise in their fit with each other that they are dangerously NON-interchangeable.

Eisner’s comic detailed why and how to clean and lubricate the M16. It recommended, “Clean your rifle every chance you get—3-5 times a day’s not too often in some cases.”

So much for “self-cleaning.”

(Will Eisner was so beloved as a teacher and exemplar of comic art, the annual prizes given “for creative achievement in American comic books” are called the Eisner Awards in his honor. How did he come to pen a sexy, savvy maintenance manual for a troubled weapon in Vietnam? The story is worth telling as an example of how seriously the military takes maintenance. When Eisner was drafted into the Army in 1942, he was already a recognized artist for his comic series, The Spirit. He wrote later that he was assigned to work on Army publications for

a new program called “preventive maintenance.” This was a unique concept in military training because it required a certain amount of voluntary participation. The army, more mechanized than it had ever been, was sensitive to the problem of equipment failure due to neglect. The desire to enlist troop enthusiasm for preventive maintenance became a major mission. It was obvious to me that comics would be the best way to publish information about field-fixes and to teach bootstrap repair under combat conditions. The concept was easy to sell; in wartime, the military is responsive to innovation.5He was the founding artistic director of PS, The Preventive Maintenance Monthly, and continued in the role as a civilian until 1971. That’s why the Army called on him in 1967 to create the M16 manual. He wrote later that he spent a month in Vietnam researching: “My job was to visit field units and pick up maintenance stories from automotive and armament shops.”6 )

Long before Will Eisner was celebrated for his graphic novels, he was the founding artistic director of PS, The Preventive Maintenance Monthly for the US Army as it geared up for the Korean War. This was his cover of the premiere issue in June 1951.

Who allowed such a lemon as the M16 to become America’s standard infantry weapon in Vietnam? According to former US Marine officer C.J. Chivers, author of The Gun, “The M16’s journey was marked by salesmanship, sham science, cover-ups, chicanery, incompetence, and no small amount of dishonesty by a gun manufacturer and senior American military officers.”7 All of that fed the scandal of the gun’s early failure in Vietnam, but the core problem was the misdirected design of the rifle itself. The original design specs show why the M16 and the AK-47 went in opposite directions in regard to maintenance.

Both weapons were invented by brilliant innovators operating outside the mainstream of government-supported gun designers. Neither of them was a formally trained engineer. The AK-47’s inventor, Mikhail Kalashnikov, was a lifelong tinkerer, inventor, and poet. He had been wounded in action while serving in a Soviet tank unit in World War II. Eugene Stoner, who developed the rifle that became the M16, was an ex-Marine who served in the Pacific. His employer was a private company called ArmaLite that pioneered using new materials such as aluminum and plastic for a lighter-weight gun.

For years, military researchers in America had investigated the potential benefits of bullets smaller than the military world-standard .30 caliber (7.62 mm). A .22 caliber high-velocity round at half the weight had less recoil—which improved accuracy—and it had greater lethality on impact because of its extreme velocity. The lighter ammo meant a rifleman could carry twice as much. Accordingly, in 1957 a formal request came from the Army

to develop a .223-inch caliber (5.56 mm) select-fire rifle weighing 6 lb (2.7 kg) when loaded with a 20-round magazine. The 5.56 mm round had to penetrate a standard U.S. helmet at 500 yards (460 meters) and retain a velocity in excess of the speed of sound.”15 Reliability and maintainability were not mentioned in the specifications.

Stoner at ArmaLite designed the AR-15 to meet those specs. One early unofficial tester was Colonel David Hackworth, an officer so dedicated to troop effectiveness he was known as “Mr. Infantry.” He noted that the new rifle looked “small and light, with lightweight ammo—at first glance, exactly what was needed.” He continued:

I took the weapon out and pumped thousands of rounds through it in every conceivable situation an infantryman might find himself—in sand, mud, cold, rain, and dense foliage as close to “jungle" as I could get at Fort Campbell. I took it apart, put it together, fired it dirty, fired it clean. And whatever the situation, the AR-15 did one thing with consistency: it jammed. Far more than it fired…. The AR-I 5 would never be worth a pinch of salt as an infantry weapon. It just wasn't rugged enough. It wasn't GI-proof. The thing required almost surgical cleanliness (damn hard to achieve on a battlefield) and exacting maintenance that the average Airborne infantryman wasn’t going to perform in a combat situation.8Whereas the 1820s Ordnance Department had pushed hard for “practicability” in John Hall’s muskets, the 1950s Ordnance Corps focussed on rifle-range performance. They never conducted battle-realistic tests like Colonel Hackworth did. When Colt Firearms took on manufacturing the new rifle, renamed the M16, the Ordnance Corps introduced three additional features that inventor Stoner said would degrade the gun’s performance, and they did. For spurious reasons, the Corps experts added a useless handle to the bolt; they altered the rifling in the barrel in a way that reduced the gun’s lethality; and, worst of all, a change they made in the bullet’s gunpowder created two additional causes of jamming. The new powder fouled the rifle and also made it fire too rapidly on automatic and then jam.

Tens of thousands of the futuristic, unproven M16s were deployed to the American and South Vietnamese troops. The rifles corroded rapidly in Vietnam’s tropical humidity, and their vaunted accuracy at 500 meters was of little use for fighting in jungle so dense that some soldiers wound up having to use their jammed M16 as a club in hand-to-hand combat. The primitive-seeming AK-47 still had battlefield advantages over America’s state-of-the-art assault rifle.

In 1990 Eugene Stoner (left, with his M16) met Mikhail Kalashnikov (right, with his AK-47). They traveled together and became friends. In many of the world’s wars since 1965, the two guns were on opposite sides.

The AK-47 had a quite different design history. During the months in 1941 that Mikhail Kalashnikov spent recovering from his wounds in a military hospital, he overheard other soldiers repeatedly complaining about the unreliability of the rifles they had been issued. As soon as he got out of the hospital, he set about designing a better gun. “His only goal,” according to the book AK-47 by Larry Kahaner, “was to build a weapon that would work every time.” Like the designers of the Lada three decades later, he and the engineers he worked with were realistic about their customers’ situation. They knew that Soviet soldiers were mostly conscripts, many unable to read or write. There would be no manuals and probably no training in rifle maintenance. Field stripping and cleaning had to be easy and obvious. And manufacture had to be cheap, ideally with stamped rather than milled parts, because they were going to make a great many guns. No one cared what it looked like.

The answer to all those requirements was simplicity. Kalashnikov was guided by the words of Georgy Shpagin: “Complexity is easy; simplicity is difficult.” The route to simplicity was continuous paring down. Repeated field testing by soldiers led to hundreds of refinements, each time toward greater reliability and ease of use. This was a case where reducing precision helped. The AK-47 book says Kalashnikov designed the “components with looser tolerances, more space between parts. Instead of dirt or sand clogging the gun, debris was thrown off in the firing process—like a dog shaking off water.”9 Unlike the M16, Kalashnikov’s gun actually was self-cleaning.

Besides being deliberately loose in their fit, some parts that looked unnecessarily large had a reason for their size. C. J. Chivers explains in The Gun, “The combined bolt and gas piston were… massive, and by giving these parts heft, the designers provided the AK-47’s operating system an abundance of energy every time a shot was fired… to push through any dirt or accumulated carbon inside the weapon.”10 The rifle could power through gunk that would paralyze the lighter, finely tuned M16. It has what engineers call "forgiveness." It forgives neglect. It forgives mud, sand, and ill usage.

The crude-looking but highly evolved AK-47 had just 73 parts. The snazzy M16 had 144 parts and required "surgical" care. It assumed a fully stocked supply line and skilled armorers with factory-level repair facilities nearby. It was--and is--a sophisticated weapon that depends on sophisticated support.

In Vietnam the most common cause of jamming in both rifles—far more common in the M16— was when a spent casing got stuck in the chamber instead of ejecting. There was no way to claw it out. The only way to remove it was to run a cleaning rod down the barrel and push it out. The AK-47 had its cleaning rod mounted under the barrel, in immediate reach. The early M16s had no cleaning rods. The later ones had a multi-part screw-together rod stashed in a compartment in the butt of the gun. When your gun jams in a firefight, you’re most likely flat on the ground or running—no place to be screwing together rod parts. “The experienced trooper,” advised the Army Information Digest, “tapes a cleaning rod to his M16 to unjam it when a cartridge sticks in the chamber.”11

In emergency situations, it’s best to have the needed tool next to the task.

After the Viet Cong triumphed over America, the AK-47 became world-renowned as the underdog’s weapon of choice, and it was adopted—with Soviet largesse—throughout the developing world. In 2001, the Secretary-General of the United Nations, Kofi Annan, wrote:

In some places, an AK-47 assault rifle can be bought for as little as $15, or even for a bag of grain. They are easy to use: with minimal training, even a child can wield one. They are easy to conceal and transport. Since they require little maintenance, they can last for decades. The world is flooded with small arms and light weapons numbering at least 500 million, enough for one of every 12 people on earth…. When they fall into the hands of terrorists, criminals and irregular forces, small arms bring devastation. They exacerbate conflict, spark refugee flows, undermine the rule of law, and spawn a culture of violence and impunity.”12(Meanwhile in America, the civilian version of the M16 is the AR-15—a semi-automatic, magazine-fed assault rifle that differs from the M16 mainly in its legally required inability to fire in full-automatic mode. It is America’s most popular gun for mass shootings. In my view, AR-15s are weapons of war that should, like hand grenades and mortars, be outlawed for civilians, but 20 million American civilians own them.13 In the school shootings that involve an AR-15, you seldom hear of a child surviving being shot. The high-velocity small bullet is designed to tumble when it hits flesh. It tears children apart.)

Far the most popular infantry weapon in the world, especially for conflicts in developing nations, AK-47s were aggressively distributed by the Soviet Union during the Cold War. The owner of this one is a Dinka man in Sudan in 2010.

“With minimal training, even a child can use one,” wrote Kofi Annan, Secretary-General of the UN. Here in a Gaza refugee camp in 2000, a young girl is trained by a Palestinian policeman on how to disassemble and reassemble an AK-47 for cleaning.

“Since they require little maintenance,” Kofi Annan wrote, “they can last for decades.” This AK-47, manufactured in 1954 in the Soviet Union, was still in use 55 years later in Afghanistan. The disassembled parts are, from the top: receiver cover, recoil assembly, and bolt carrier with gas piston.

Fifty years after the Vietnam War, the M16 and AK-47 remain the world’s standard assault rifles. Both, in their profoundly different ways, are brilliant designs. A total of eight million M16s in several variations have been sold for military use. AK-47s, in many variations, have sold over 100 million. An M16 costs $650; the official price of an AK-47 is $150.

As Ford’s Model T and the Volkswagen bug showed, cheap, clunky, sturdy, and maintainable wins time after time. Russians sometimes excel at designing for those traits. It’s there in the Lada car, in Kalashnikov’s AK-47 rifle, and in the Soyuz rocket—as we’ll see.

"Two Assault Rifles" footnote - Corpsman Wike

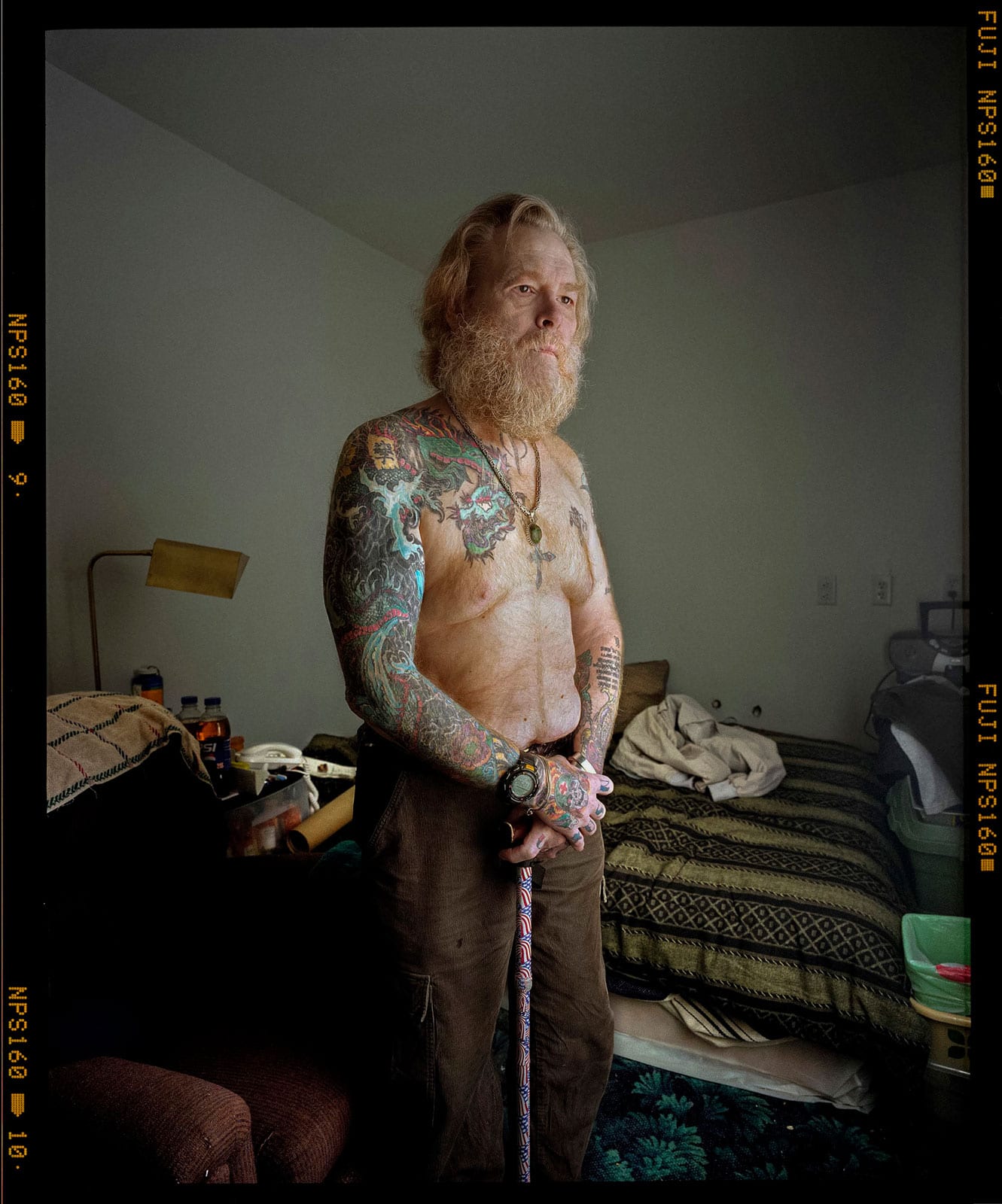

After the Vietnam War, where Catherine Leroy was herself wounded just a week after the Hill Fights, she went on to a distinguished career as a war photographer, covering combat in Lebanon, Northern Ireland, Cyprus, Somalia, Afghanistan, Iraq, Iran, and Libya. In 2005, Paris-Match commissioned her to visit and photograph the subject of her most famous images, Vernon Wike.

Leroy found Wike in Prescott, Arizona, in bad shape but delighted to see her again. He looked much older than his 58 years. On his body were nineteen warrior tattoos, including the names of comrades who had died in Vietnam. He had burned through four marriages and had two sons who wouldn’t speak to him. Once, when he had collected a horde of weapons, he had had an armed standoff with police at his remote cabin. Later, the cabin burned down, and Wike lived alone in a tiny room in town when Leroy found him. Two days after she photographed him, he had a stroke that blinded him and paralyzed half his body. He died soon after. It was Catherine Leroy’s last commission. She died a year later in California, age 61. Her life’s work is collected online.30

Former Corpsman Vernon Wike, March 1, 2005.

It was her last public photograph, which like her first public photograph of the same man, depicted his suffering indelibly and honorably. The photos are honorable because, in the first case, she was in the same danger as Wike. It’s not a telephoto shot.

The final image honors their friendship. She had visited him before. She was recording art he was proud of—his tattoos. There is so much craft in the image. The corners of the ceiling converge on his face. She had done professional fashion photography, and it’s there in the window lighting and in her evoking of the room—of his situation. She photographed his dignity--the dignity of a ravaged man.

To my eye it is a singularly great war photograph. It’s better than iconic. Iconic is the Iwo Jima flag-raising photo—a marvel of composition. Leroy’s photo of Wike is one you can study and study for its wealth of telling detail and its stark beauty.

(End of "Two Assault Rifles" sub-digression)