Digression 2: From MANUALS to YOUTUBE (with a detour) - Great Manuals in History

TThe Wikipedia entry on John Muir says this:

Muir's self-published edition of How to Keep Your Volkswagen Alive: A Manual of Step by Step Procedures for the Compleat Idiot sold more than two million copies to become one of the most successful self-published books in history, while its wry subtitle preceded (and likely inspired) the unending flow of "for Dummies" books from IDG Publishing and other "idiot's guide to ..." books.(About 2,500 “…for Dummies” manuals have sold 200 million copies since 1991. Among the titles are Beekeeping, Motorcycling, Pickleball, Cybersecurity, and Ukelele. The similar Idiot’s Guide series has 120 titles in print, with subjects ranging from “pregnancy for dads” to flipping houses; a different, Complete Idiot’s Guide series, has 183 titles, with subjects from world history to street magic .)

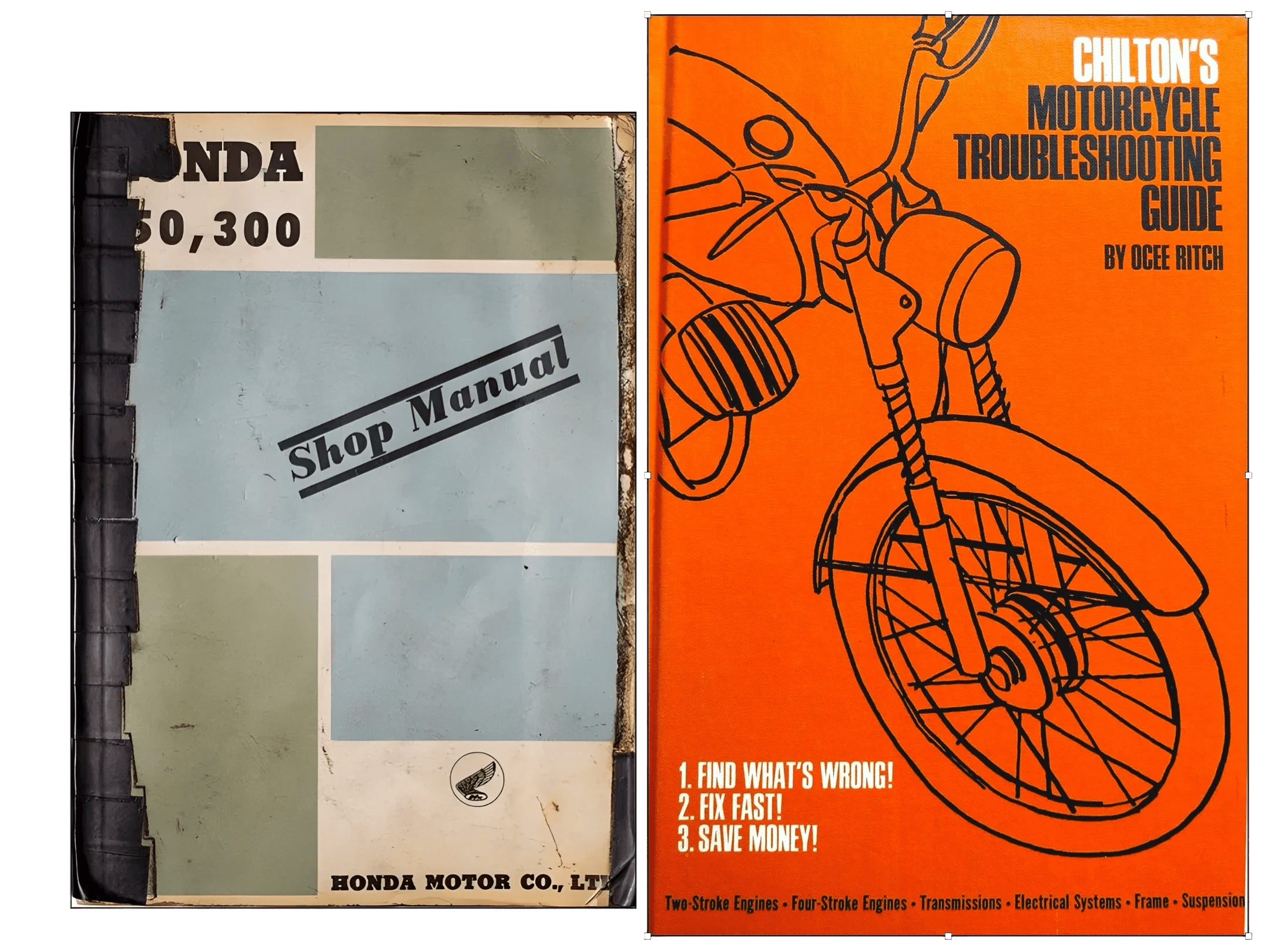

Once a device has a large enough user base, two manuals are often considered essential. One is the shop manual that comes from the manufacturer. The second is an emergent third-party manual that goes deeper and wider, often with an artfulness and outsider attitude that the manufacturer would never dare to display. Robert Pirsig carried two manuals on his motorcycle along with his tools—the Shop Manual from Honda for the specifics of his Super Hawk and Chilton’s Motorcycle Troubleshooting Guide for the then-current state of the art of motorcycle maintenance.

These two motorcycle manuals accompanied Robert Pirsig on the 1968 road trip that inspired Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. His 1964 Honda Shop Manual is now at the Smithsonian National Museum, along with the Honda Super Hawk he rode in 1968.

Unlike an owner’s manual, a shop manual—sometimes called a “workshop manual” or “service manual”—is all about repair, complete with parts lists and wiring diagrams. The best ones have a hands-on, user-based perspective and lucid prose. The worst defy understanding. In the Shop Class as Soulcraft book, Matthew Crawford deplores how “The writers of modern manuals are neither mechanics nor engineers but rather technical writers.”1 Often the clueless text for foreign-made items has gone through an even more clueless translator.

A good point-of-view photo. “Use the proper size box-end wrench or socket wrench to remove the oil drain plug and avoid rounding it off,” advises the Haynes Pontiac G6 (2005 thru 2009) Online Auto Repair Manual.

A YouTube video has all the advantages of a still photo plus many more. In this video (by T.J. Lewis, 6 minutes, 2017) for changing the oil on a Pontiac G6, you notice that you turn the socket wrench counter-clockwise, pushing with your thumb, to loosen the drain plug. Then you finish unscrewing it with your fingers. You’ll probably get some oil on your fingers when it starts pouring out.

The best manuals for amateurs include point-of-view photos, often with a hand in the foreground using the right tool at the right place in the right way. The Haynes Vehicle Workshop Manuals are renowned for this. (The equally famous Chilton Repair Manuals, designed for professional mechanics, are richer with detailed advice than with photographs.)2

For usefulness in depth, nothing matches a comprehensive, encyclopedic manual. The bigger, the better. The book iPhone: The Missing Manual: The Book That Should Have Been in the Box has 719 pages and weighs two pounds. The authoritative text for every known ailment of the human body, all in one book, is The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy; the 20th edition weighs in at six pounds and 3,530 pages. (That’s the edition for medical professionals. For family use, you get The Merck Manual Home Health Handbook—four and a half pounds, 2,500 pages.)

Manuals have long been the primary point of reference for maintainers, but most manuals are ephemeral, confined to a subject and time that soon passes. Some, though, like John Muir's, have such uniqueness and impact on their times that they live beyond them. Here are six that strike me that way. Three were created explicitly to break through class barriers.

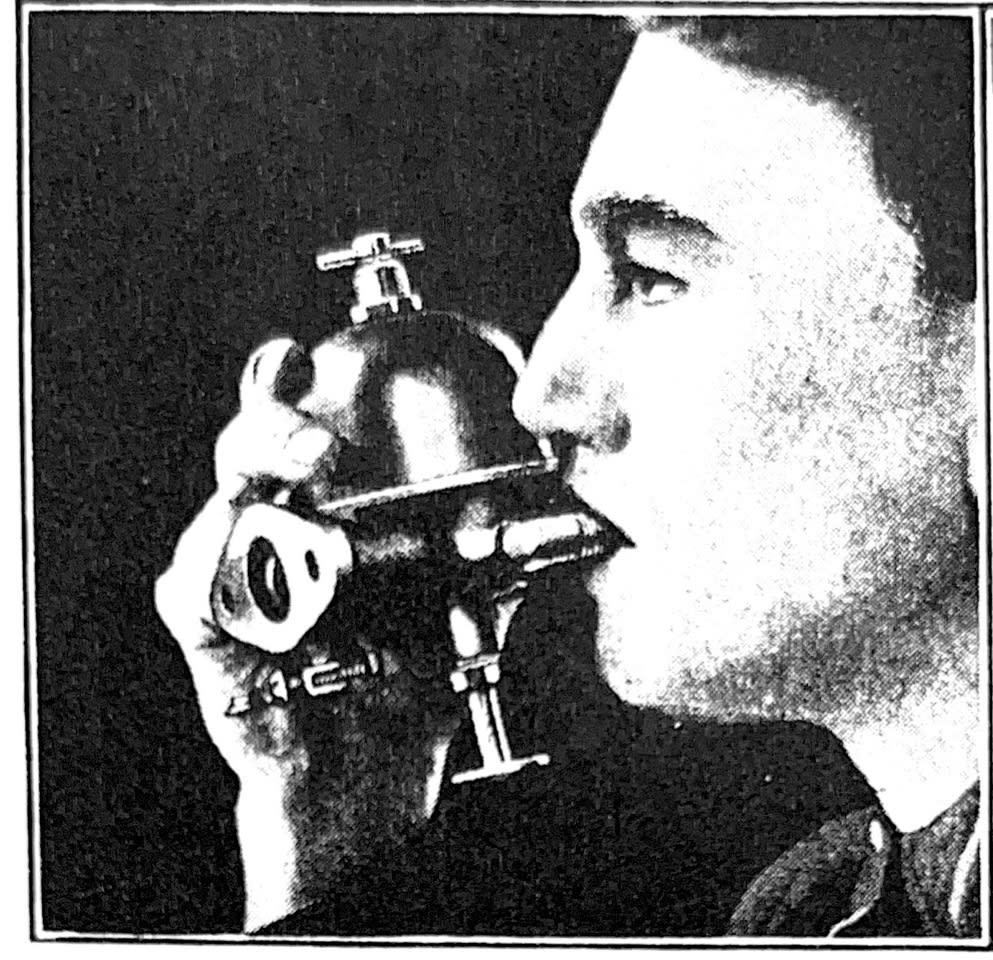

Model T Ford Service manual, 1927: “Test tightness of gasoline inlet needle by turning carburetor upside down, and sucking lightly on the fuel inlet elbow. If the needle is properly seated, the tongue or lips will stick to the elbow in the same manner as with a small bottle.”

1. Some manuals excel in evoking a sense of discipline. Ford’s 1927 service manual for Model T mechanics begins: “We will first describe, step by step, the correct procedure in disassembling, and reassembling the car.”3 They mean the whole car, just like the elder George Dyson with his new motorcycle in 1913 . The whole book is that thorough. As for adding water to the batteries, Ford’s advice is: “Distilled water or clean rain water that has not come in contact with metal should be used for this purpose.”4 Sucking on the carburetor to test it, collecting rainwater for the battery—those were the days.

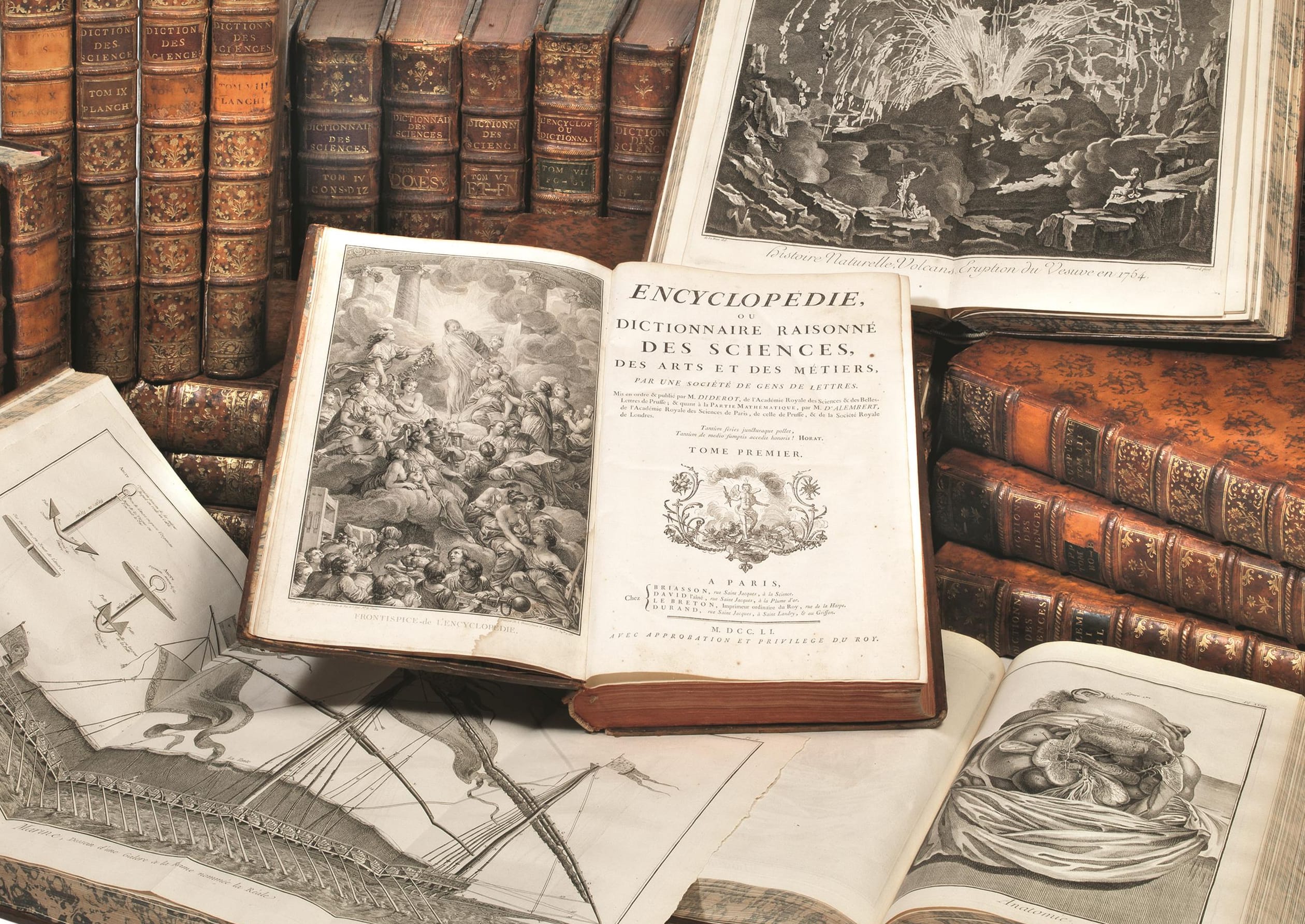

Described as “the single greatest publication of the Enlightenment,10” and “the greatest intellectual enterprise of the 18th century,” France’s Encyclopédie, ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, took 25 years to complete. It contained 74,000 text entries and 3,100 engraved illustrations.

2. In the 18th Century, a manual-like set of volumes from the French Enlightenment transformed Western thought. It was the Encyclopedia or Dictionary of Sciences, Arts, and Trades, published between 1751 and 1772. Despite its length—35 volumes filling a twelve-foot shelf—it was a best-seller. The primary editor was a Parisian writer-philosopher named Denis Diderot, who specialized in warring with the powers of the ancien régime. “With the guts of the last priest,” he wrote, “let us strangle the last king.”5

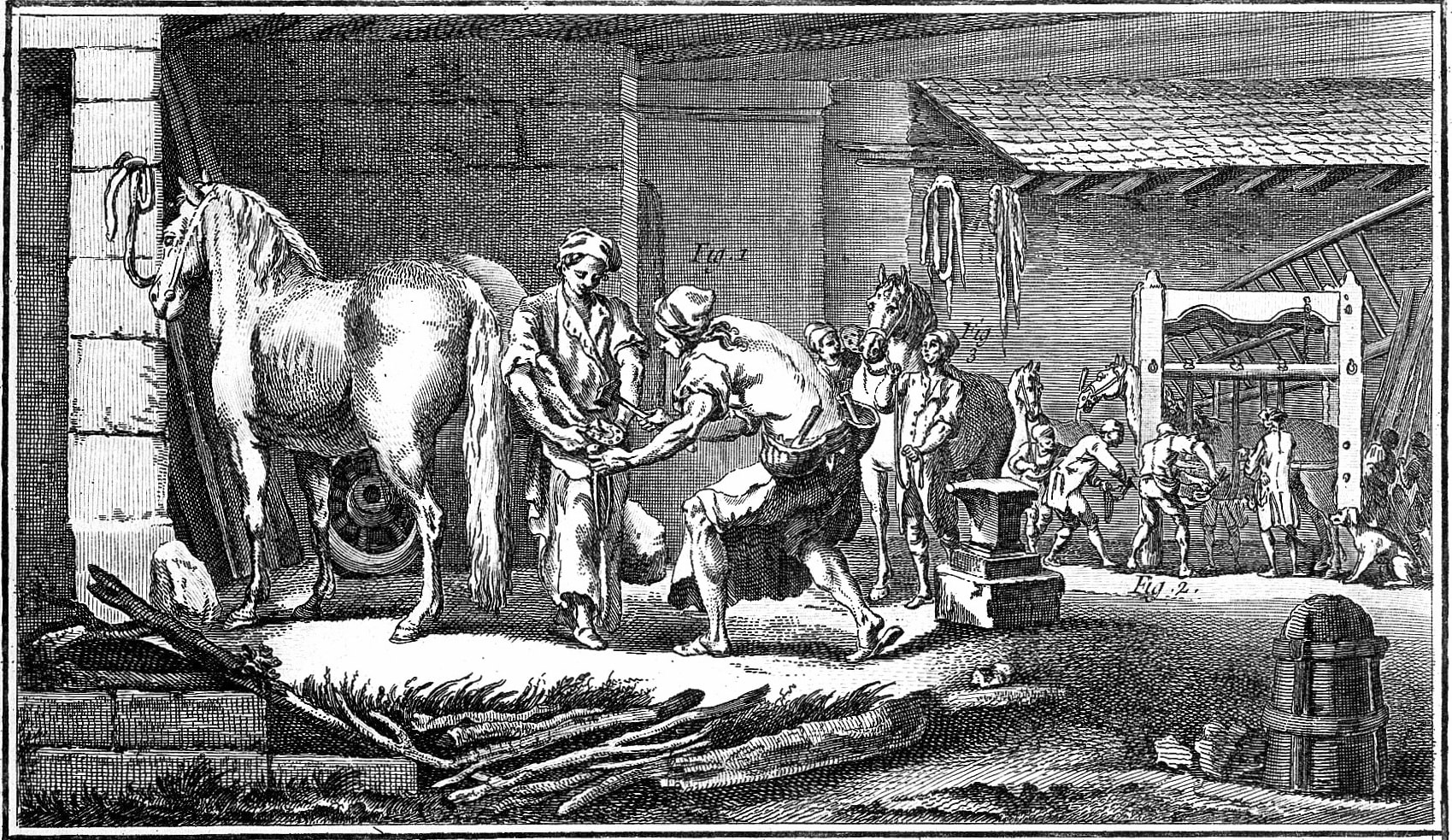

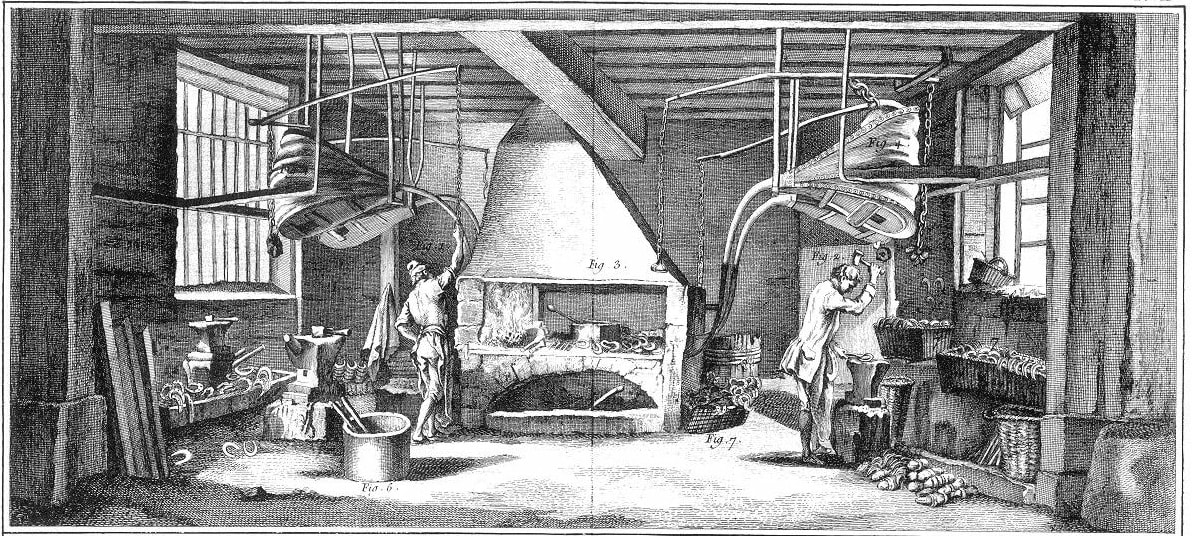

Maintaining a horse requires the services of a farrier to shoe the horse and treat its ailments. These plates in Diderot’s Encyclopedia show in detail the work and tools of a farrier in 18th Century France. On the left, an apprentice holds the horse’s hind foot while the master demonstrates how to nail the horseshoe to the hoof. On the far right is an apparatus for keeping a horse immobile while workers lift one leg after another for shoeing.

Here are two stages of the farrier’s blacksmith work. On the left, he heats the forge by hauling on the chain overhead to expand the bellows. The weight of the rock hanging from the bellows then contracts it rapidly to blast air onto the glowing coals in the forge. On the right, the smith hammers a red-hot horseshoe into shape on the anvil.

Diderot’s biographer, P. N. Furbank, writes that for Diderot the Encyclopedia was:

A rebuke to court culture and its attitudes, according to which it was below the dignity of a person of fashion or standing to know the technical detail of any craft…. In the eyes of Diderot, the son of a master cutler, it was a matter of doing justice to a social species, the skilled craftsman, whose role in the national life was absurdly undervalued.6He once remarked, “Only the rich can afford to be stupid; for others, ability is a necessity, not an option.”7

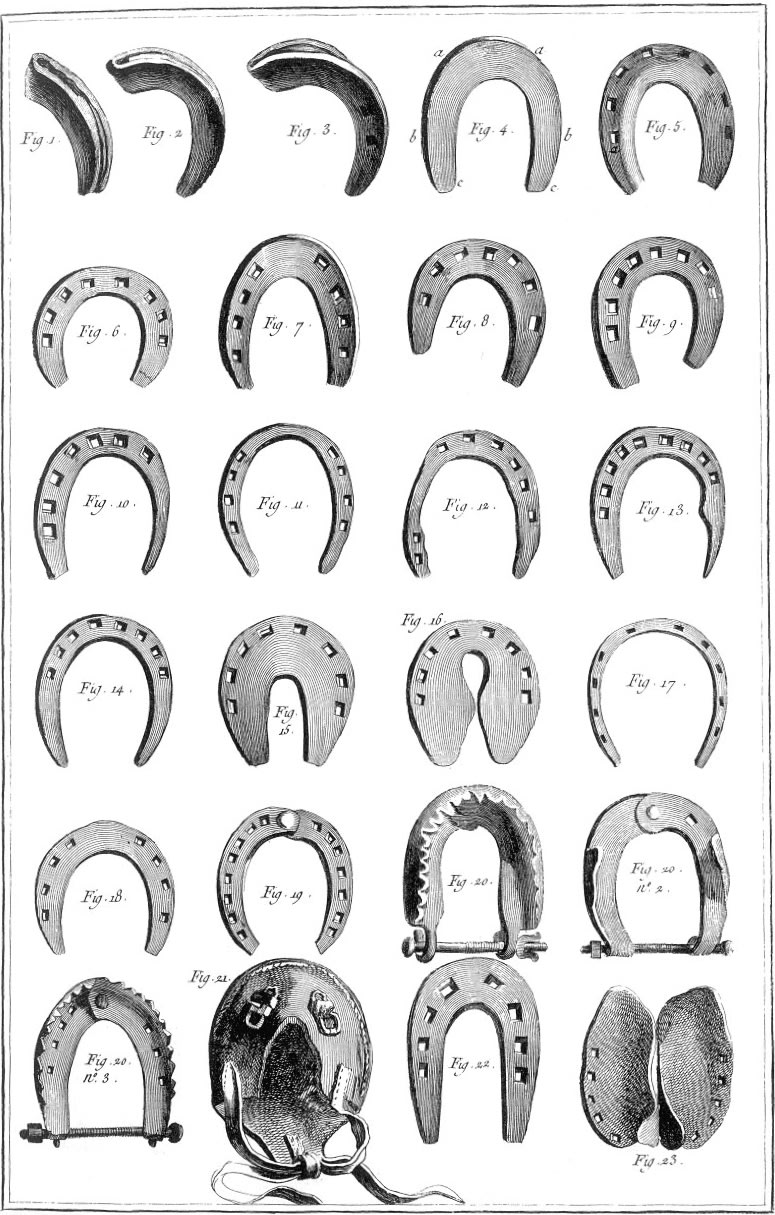

Here the top row shows the sequence of shaping a folded strip of iron into a horseshoe and adding holes for the nails. The rest of the plate illustrates horseshoes fashioned for various conditions of the horse’s hoof and varieties of ground to be ridden on. Figures 19 through 21 show adjustable shoes that a rider can use to temporarily replace shoes lost while riding.

Though the Encyclopedia had numerous contributors, Diderot himself wrote 7,000 of the 72,000 entries, many of them about craft techniques he researched in person. He wrote:

We addressed ourselves to the most skilled workers in Paris and the kingdom at large. We took the trouble to visit their workshops, to interrogate them, to write under dictation from them, to follow out their ideas, to define, to identify the terms peculiar to their profession.8In an entry about “Art” ( by which he meant “craft” or “technology”) he honored the industrial tools he encountered in the workshops:

In what physical or metaphysical system do we find more intelligence, discernment, and consistency than in the machines for drawing gold or making stockings, and in the frames of the braid-makers, the gauze-makers, the drapers, or the silk workers?9He often tried operating the machines himself and discovered the difficulty of getting the process exactly right. He would, he said, “become an apprentice and produce bad results so as to be able to teach people how to produce good ones.”10

The Encyclopedia’s entries were illustrated with 3,100 plates portraying in meticulous detail the workshops and tools of every trade. The workers in the images are always depicted with dignity, performing their specialty with calm assurance. This accorded with the Encyclopedia’s credo, writes Richard Sennett in The Craftsman: “It celebrated those who are committed to doing work well for its own sake; the craftsman stood out as the emblem of Enlightenment.”

In his entry on the word “métier” (trade, profession, calling) Diderot wrote:

We owe to the métiers all objects necessary in life. Those who take the trouble to go into the workshops will find usefulness & good sense everywhere…. The poet, the philosopher, the orator, the minister, the soldier, the hero—they all would be naked & without bread without the artisan whom they all despise.11

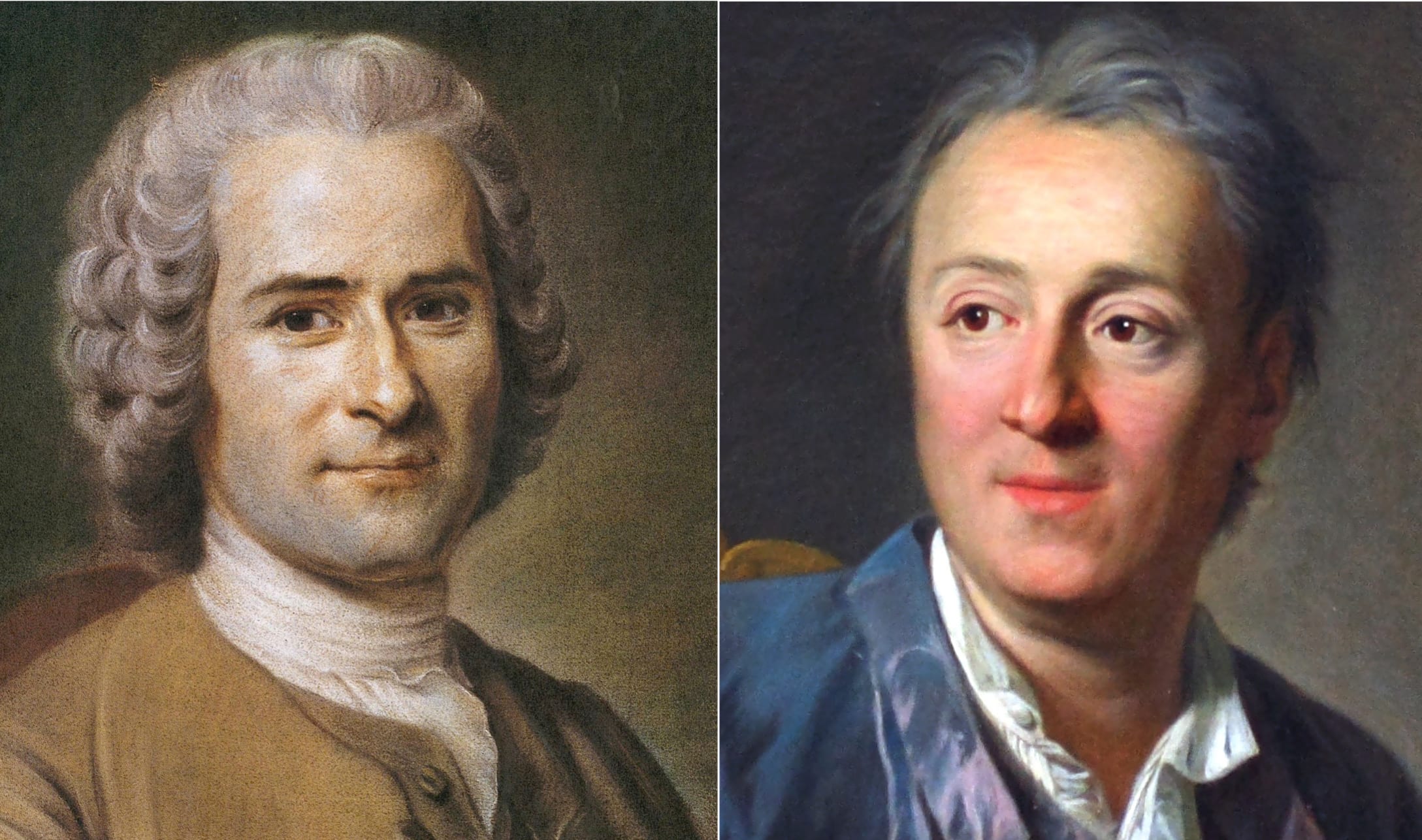

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (left) was a good friend of Denis Diderot (right) and an early contributor to the Encyclopedia. Later, as Rousseau succumbed to growing paranoia, he became an enemy of the Encyclopedists and attacked Diderot. In the course of Rousseau’s adult life, he transformed himself from an influential participant in the French Enlightenment to its most lethal critic

A fellow troublemaker and close friend of Diderot was Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Along with his acclaimed discourses on human inequality and the social contract, Rousseau wrote several early entries for the Encyclopedia, drawing on his lifelong interest in music. But gradually he turned against the encyclopedists and Diderot. He eventually assailed all his old friends and denounced the rationalism and practicality of the Enlightenment, celebrating instead emotion, intuition, and the primacy of personal passion. In his later writings, he relished parading his own melancholy and alienation. Diderot finally wrote of him, “This man is a monster.”12

Much that became monstrous in the French Revolution emerged from popular devotion to Rousseau’s ideas. One of his most fervent followers was the murderous Robespierre, who declared in a 1794 tract, “Terror is only justice—prompt, severe, and inflexible.” A 1997 book titled The Idea Of Decline In Western History, by Arthur Herman, makes a persuasive case that Rousseau’s anti-rational Romanticism directly inspired two centuries of gaseous, heroic, often suicidal pessimism about civilization. Rousseau declared, “Everything degenerates in the hands of men.” Nietzsche echoed, “There is an element of decay in everything that characterizes modern man.” To my ear, the echoes continue today in every exuberant user of the words “existential threat to humanity.”

Two great political revolutions in the 18th century were inspired by the Enlightenment thinkers that included Diderot and Rousseau. The American one might be called Diderot’s revolution—the creation of a nation founded on two Enlightenment documents, The Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution. The French Revolution was Rousseau’s. What it did to Diderot’s masterwork is summarized by Phillip Blum in his 2005 book, Enlightening the World::

The Revolution had no time for the generosity of spirit that marked Encyclopedist thought. The values espoused by the Encyclopedists, which had once seemed likely to dominate for decades, were swiftly crushed by Europe's first, though short-lived, totalitarian regime. When the monarchy was restored, the Encyclopedists were seen as sowers of unrest, rebellion, and impiety. The Encyclopédie was consigned to oblivion.13General Gribeauval’s rational system of uniformity of manufacture in France’s weapons also was canceled by the sanscoulottes, as I mentioned earlier, and the Industrial Revolution was kept out of France for half a century. By contrast, the triumph of the Industrial Revolution in Britain was closely linked with the lasting effects of the Scottish Enlightenment. Scotsman James Watt, inventor of the steam engine, communicated routinely with empiricist David Hume, economist Adam Smith, geologist James Hutton, and the scientist of gases and heat, Joseph Black. They and the rest of the Scots intellectuals manifested what has been described as

a thoroughgoing empiricism and practicality where the chief values were improvement, virtue, and practical benefit for the individual and society as a whole. Among the fields that rapidly advanced were philosophy, political economy, engineering, architecture, medicine, geology, archaeology, botany and zoology, law, agriculture, chemistry and sociology.14

A century earlier in England, in the 1650s, an impulse similar to Diderot’s drove a physician and herbalist named Nicholas Culpeper. He deplored the institutionalized secrecy and avarice of physicians. “No man,” he wrote, “deserved to starve to pay an insulting, insolent physician.”15 He set up his apothecary shop in a poor part of London and saw as many as 40 patients a day. Physicians at that time used Latin as a private code for prescriptions, for the books they wrote, and especially for discussions among themselves that patients might overhear. Culpeper defied that practice by translating the London Pharmacopoeia of medicinal drugs from Latin to vernacular English.

Culpeper’s biographer, Benjamin Woolley, describes him as a “pioneer of herbal medicine whose actions and beliefs revolutionized medicine and medical practice.”16 His reputation comes primarily from his 1652 publication, The Complete Herbal. It was, in effect, the Merck Manual of his time. The book described all the medicinal wild herbs in England and spelled out their properties, where to find them, how to prepare and preserve them, and how they could be used to treat all known ailments. He priced the book so anyone could buy it—just three pence—and buy it they did. Biographer Woolley writes, “It proved to be one of the most popular and enduring books in publishing history, perhaps the non-religious book in English to remain longest in continuous print.”17 It is available today in several editions, most of them now illustrated.

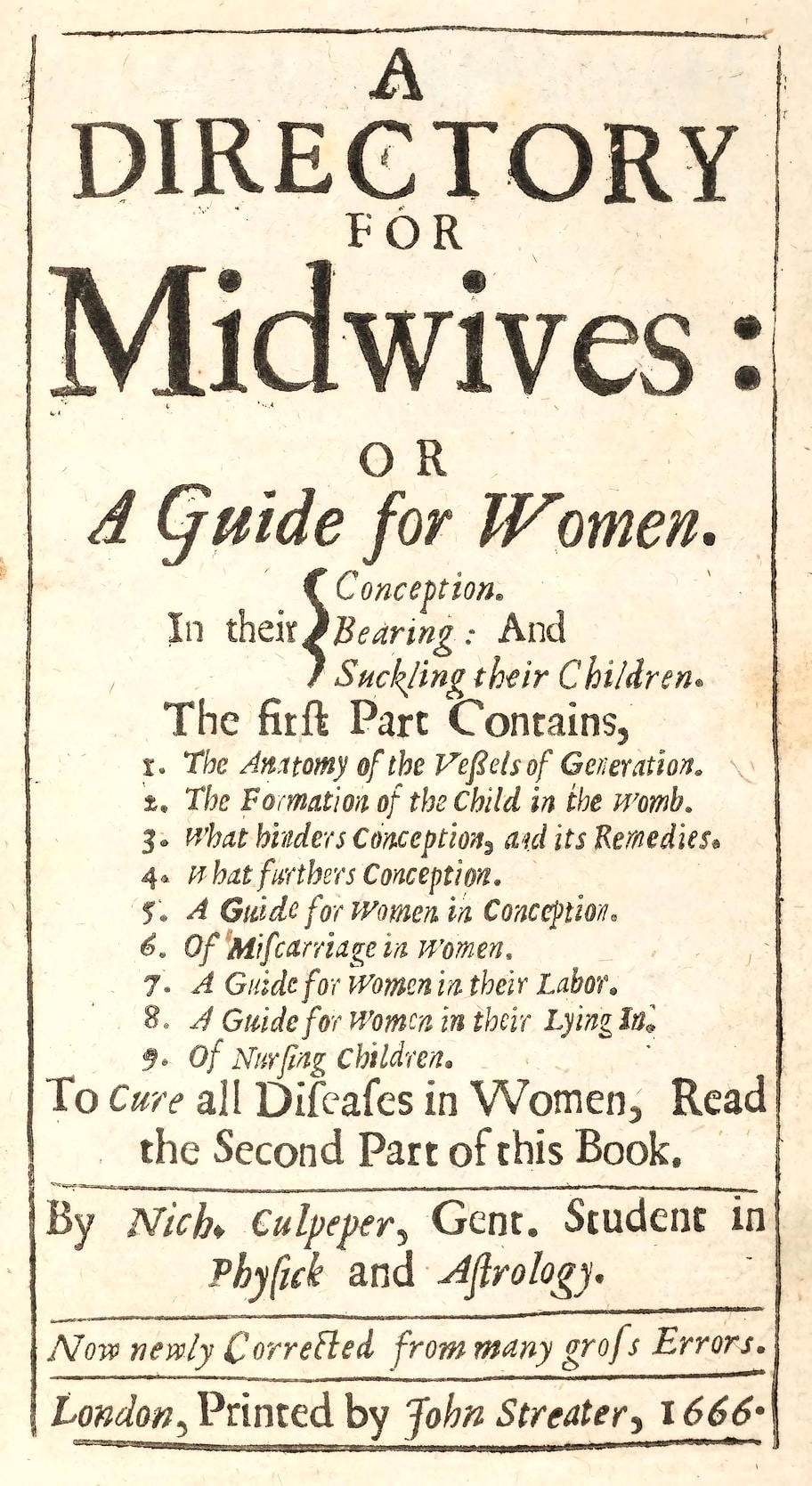

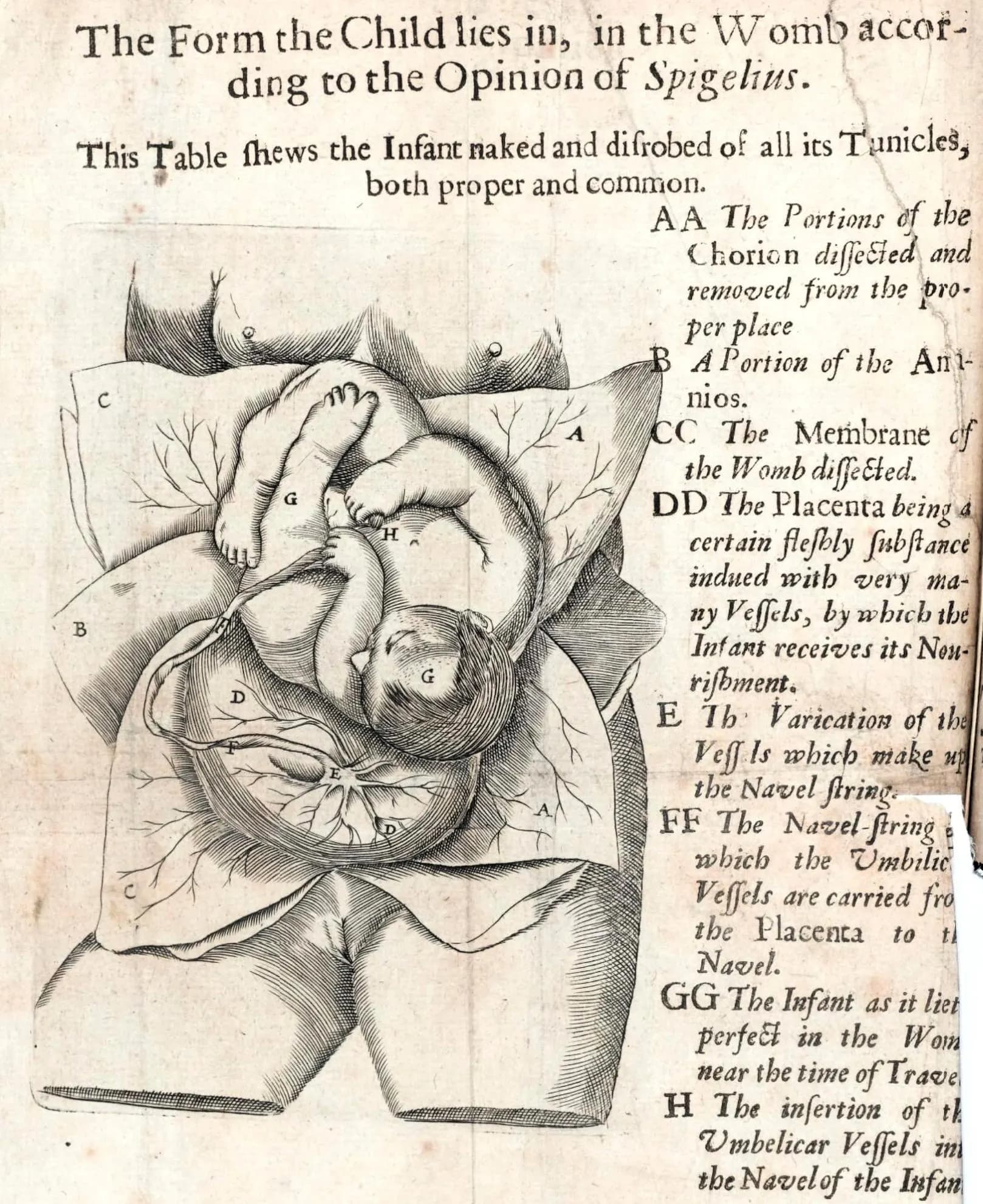

Nicholas Culpeper’s manual for midwives was so popular it went through multiple printings. This 1666 edition of his 1651 book notes that it is “Newly Corrected from many gross Errors.” (The vexation of authors with careless printers is an abiding feature of book publishing)

According to his biographer, Culpeper better understood the umbilical cord (“FF - Navel-string”) than his famous contemporary William Harvey. Harvey thought the amniotic fluid nourished the infant through its mouth. Culpeper wrote that the umbilical “is the nourisher of the infant even from the beginning of the conception, to the time of delivery, till it breath air and concoct its food as we do.”

3. A fundamental text on how to keep humanity going was Culpeper’s hugely popular Directory for Midwives, published in 1651. His biographer notes, “It was printed in pocket-sized octavo format, and written in an informal style, peppered with anecdotes and jokes18.” Along with detailed information on fertility, pregnancy, the development of the fetus, miscarriages, and childbirth, the book included lore about the sex organs. Unlike physicians such as the celebrated Dr. Willam Harvey (who discovered the circulation of the blood and wrote in Latin), Culpeper knew what the clitoris was and was for. He wrote, “In form it represents the yard of a man and suffers erection and falling as that doth; this is that which causeth lust in women and gives delight in copulation.”19 (William Harvey considered sex necessary but disgusting—something women must suffer.)

Childbirth in 17th century England was hazardous for mother and child. Culpeper ended the book’s preface with a message to the midwives he championed: “Let me intreat the favour of you all, that if you by your own experiences finds any thing which I have written in this Book, not to be according to truth,… Acquaint me with them, and they shall be both acknowledged and amended.”20

(Footnote. British novelist Ian McEwan read this section and responded with an addition:

Since you ask for suggestions, may I propose the history of manuals to the most complex thing we know? I’m thinking of childcare manuals. Over the last 3 centuries, their constant shifts in tone and emphasis give us a guide to the spirit of the age and its dreams of what we should be. In 17th Century, the business was to break the child’s will, for such was God’s will and children were little more than small unreasonable adults. In the 18th Century, romantic Rousseau-esque notions of the child trailing clouds of glory. Then Victorian strictness, Edwardian sentimentality; in 1920s and ‘30s, horrific ‘science-led’ regimes and behaviourist nightmares. Not picking up the screaming child—it must learn who’s in charge. Feeding only every 4 hours on the dot. Lots of fresh air, resist cuddling. Then came Spock—child centred care. Until recently, these manuals were mostly written by men to be read by women. The best guide to these guides is Dream Babies by Christina Hardyment.)

Enlightenment-era child-care advice was personified in the twin boys of the Blunt family in England about 1767. Philosopher John Locke urged that children be respected and challenged. “Following his ideas,” writes Christina Hardyment in Dream Babies, “parents dressed their toddlers in loose clothes and gave them small versions of adult tools to play with.”

4. The first modern-style do-it-yourself manual was titled Mechanick Exercises: or The Doctrine of Handy-Work. It was written and self-published in the 1670s by a different sort of leveler. While Diderot in the next century was an aristocrat writing for aristocrats about the trades of common people, the printer Joseph Moxon was a tradesman writing for tradesmen—and also for England’s intelligentsia. Among Moxon’s customers and sponsors were mathematician Isaac Newton, astronomer Edmond Halley, microscopist Robert Hooke, architect Christopher Wren, and naval administrator Samuel Pepys. In 1678, Moxon was the first tradesman invited to join the scientists of the Royal Society, which since its founding in 1662 had been purchasing his maps, globes, and mathematical texts.

The Royal Society had long wanted to compile a book of tradecrafts, but the scholarly thinkers didn’t have trade experience, and tradesmen didn’t write. Joseph Moxon was a tradesman who did. His self-printed Mechanick Exercises was the first-ever serialized book, released in 14 installments between 1678 and 1683. In the preface, he wrote, “Tho’ the Mechanicks be by some accounted ignoble and scandalous, yet it is very well known, that many Gentlemen in this Nation of good Rank and Quality are conversant in Handy-Works.”

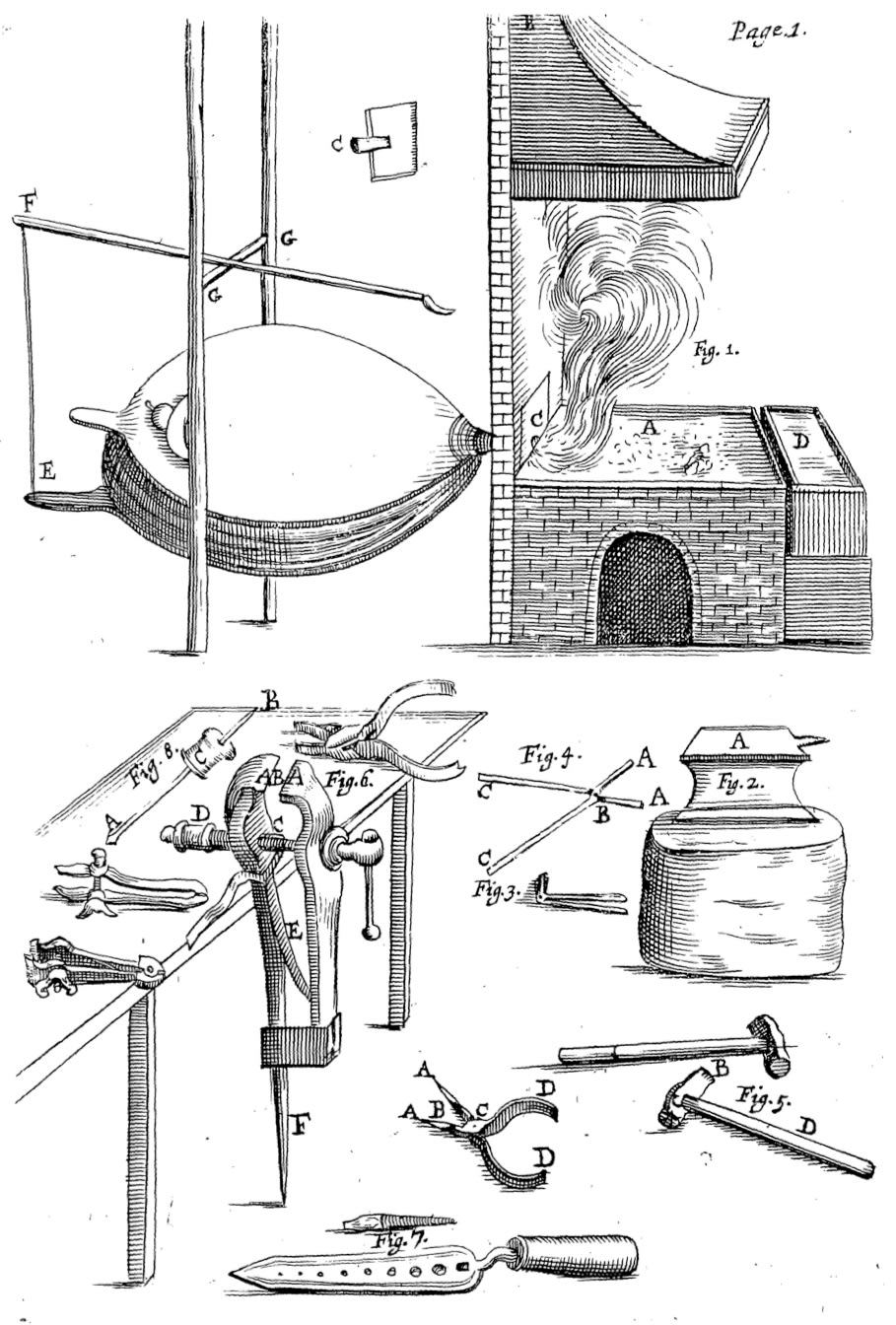

Moxon declared he was “for many Years conversant in” all the skills he wrote about: blacksmithing, joinery, house carpentry, lathe-work, bricklaying, and printing. His book had 26 plates illustrating the tools of each craft and explaining their use. He began with blacksmithing, noting that its reputation as a “Vulgar Art” was misplaced because it is foundational to everything else.

Whereas Diderot’s Encyclopedia would feature the classy blacksmith shop of France’s Royal Stables, Moxon in 1678 showed the reader how to build and equip his own shop. He advises, for example, that the anvil should be mounted on a block of wood “about two foot high from the floor, or sometimes higher, according to the stature of the Person that is to work at it.” For this illustration he spells out the names and uses of the large and small tongs (Figs. 4 and 3), hammer and sledge (Fig. 5), pole vise and hand vises (Fig. 6), pliers (Fig. 6), and screw-plate and taps (Fig. 7).

Following 62 pages of instruction on blacksmith practices, Moxon ends with this note:

Only this general Rule observe, from an old English Verse us’d among Smiths, when they Forge Edge-tools, He that will a good Edge win/ Must Forge thick and Grind thin.21Further on, in the carpentry section, where he explains “the pretty skill in driving a nail,” he mentions a diverting “little trick.” You “privately touch the Head of a Nail with a little Ear-wax” and then wager another carpenter that he can’t pound the nail in with three blows. His “Hammer no sooner touches the Head of the Nail,” writes Moxon,” but instead of entering the Wood it flies away.”

Workplace pranks are a constant, throughout history, throughout the world.

In 1683, Moxon published a second volume, this time focussed on his own trade. Titled Mechanick Exercises: Or, the Doctrine of Handy-works Applied to the Art of Printing,” it has been called “ a pivotal contribution not only to the mechanical art of printing but also to the standardisation of editorial practice.”22 It remained the authoritative text on the subject for a century. Moxon begins it by describing his own role in the complex process of printing a book:

First The Master Printer, who is as the Soul of Printing; and all the Work-men as members of the Body governed by that Soul subservient to him; for the Letter-Cutter would Cut no Letters, the Founder not sinck the Matrices, or Cast and Dress the Letters, the Smith and Joyner not make the Press and other Utensils for Printing, the Compositer not Compose the Letters, the Correcter not read Proves, the Press-man not work the Forms off at the Press, or the Inck-maker make Inck to work them with, but by Orders from the Master-Printer.23

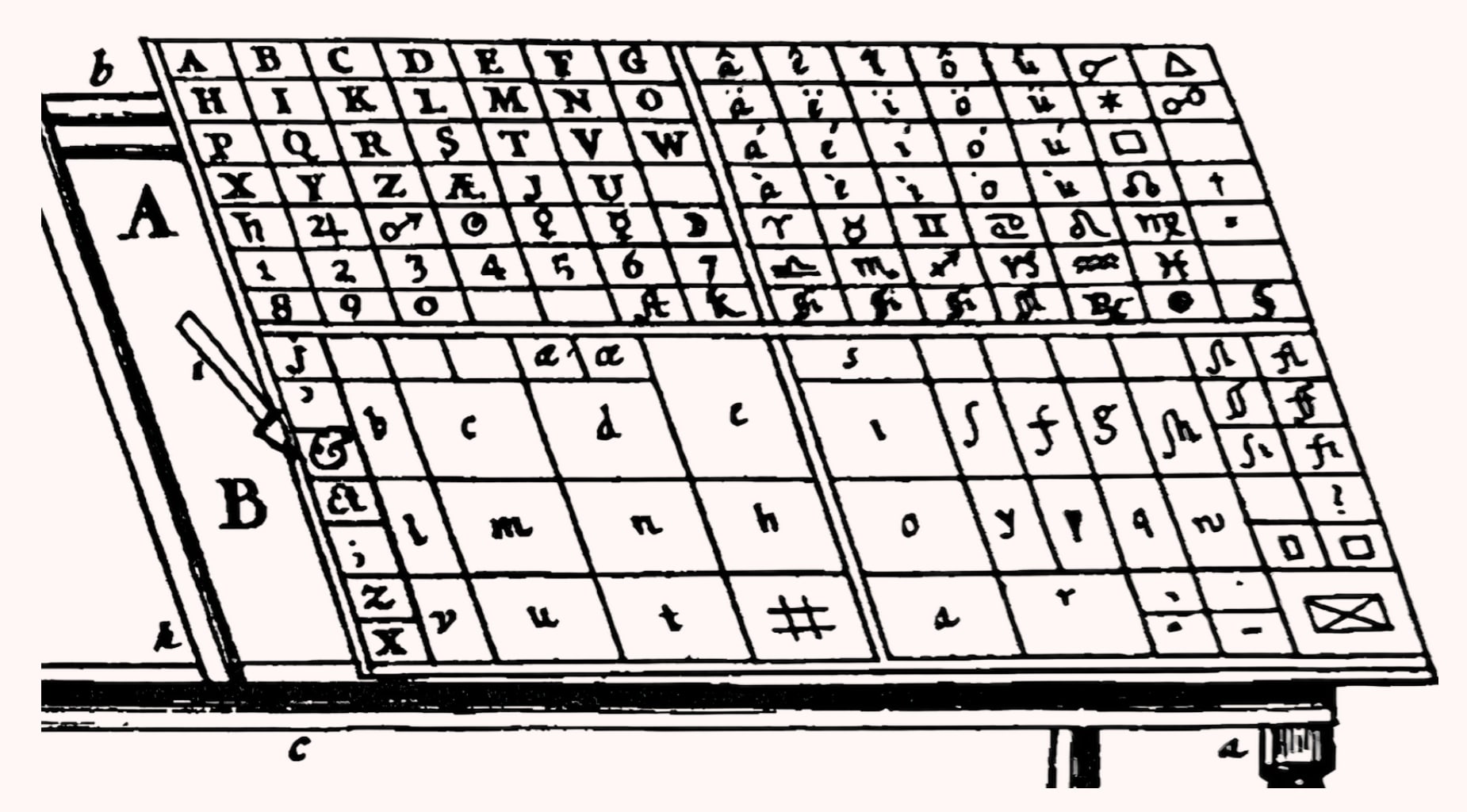

Moxon has 24 plates in his volume on printing. For this one, he explains how the cases of letters are laid out for letterpress printing. In the upper case, the capital letters are arranged in alphabetical order, but in the lower case, “Letters that are most used are laid in the biggest Boxes, about the middle of the Case, that the Compositor’s hand may have quicker access to them.”1 (Another term for the letters we still call “lowercase” is “minuscule.”) At the left of this plate is the composing stick, marked “i”.

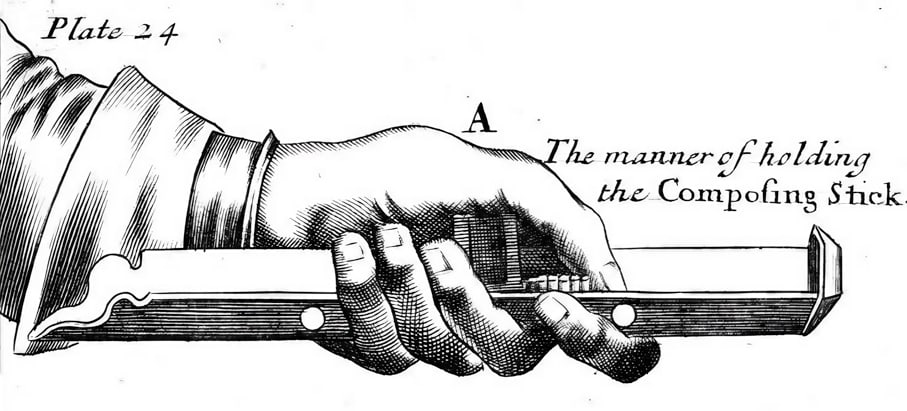

Moxon’s technique of handling the composing stick is still used by letterpress printers today: “When he Composes the Letters he holds the Composing-stick in his Left Hand, placing the Second Joynt of his Thumb over the moving Cheek of the Stick, and the end of the Ball of his Thumb reaches down to the bottom of the Cheek and Stick; so that with the end of the Ball of his Thumb he gently presses the Letter close to the Cheek, and keeps the Letters tight and square together, as he places them in the Stick successively.”

Joseph Moxon lived and suffered 17th Century London to the full. When he was 10 in 1637, his printer father was such an outspoken Puritan that he got in trouble with the government, and the family had to flee to Holland. Once Oliver Cromwell made London safe for Puritans, the Moxons returned in 1643 and put to use all they had learned about printing in Holland. Remarkably, by 1662 Joseph’s reputation as a printer of charts and globes was so high that it outweighed his history as a Puritan, and the newly installed Restoration monarch Charles II appointed him to a salaried position as “Hydrographer [cartographer] to the King.”

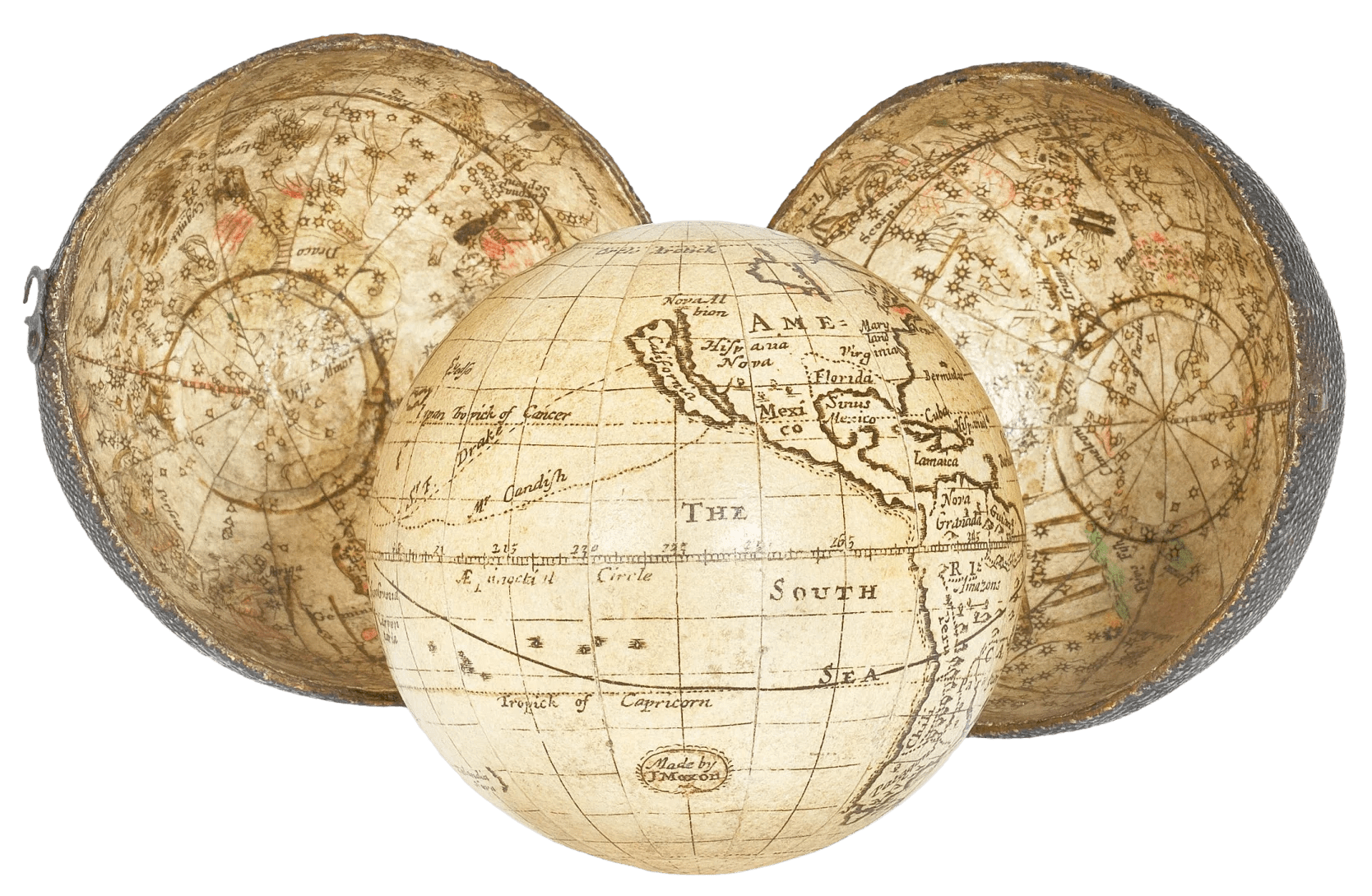

In London’s Plague Year, 1665, Moxon lost his mother, brother, wife, and their two children to the disease. The following year, 1666, the Great Fire of London destroyed his print shop and most of his stock. Yet he recovered and prospered. His most popular product was a series of “pocket globes” depicting the world’s geography on a three-inch sphere, encased in two half-spheres with a map of the heavens inside. Moxon’s biographer says that they “became both influential and fashionable… They were much sought after, and some of Moxon’s globes found their way into royal and imperial collections.”24

One of Joseph Moxon’s “pocket globes,” this one dated about 1675. At the upper-center of the globe, California is shown as an island intersected by a dotted line indicating Sir Francis Drake’s 1579 expedition. The cartouche “Made by J. Moxon” is at lower-center. This pocket globe, one of eleven made by Moxon thought to still exist, was purchased for $240,000 in 2021 at a Bonhams auction in London.

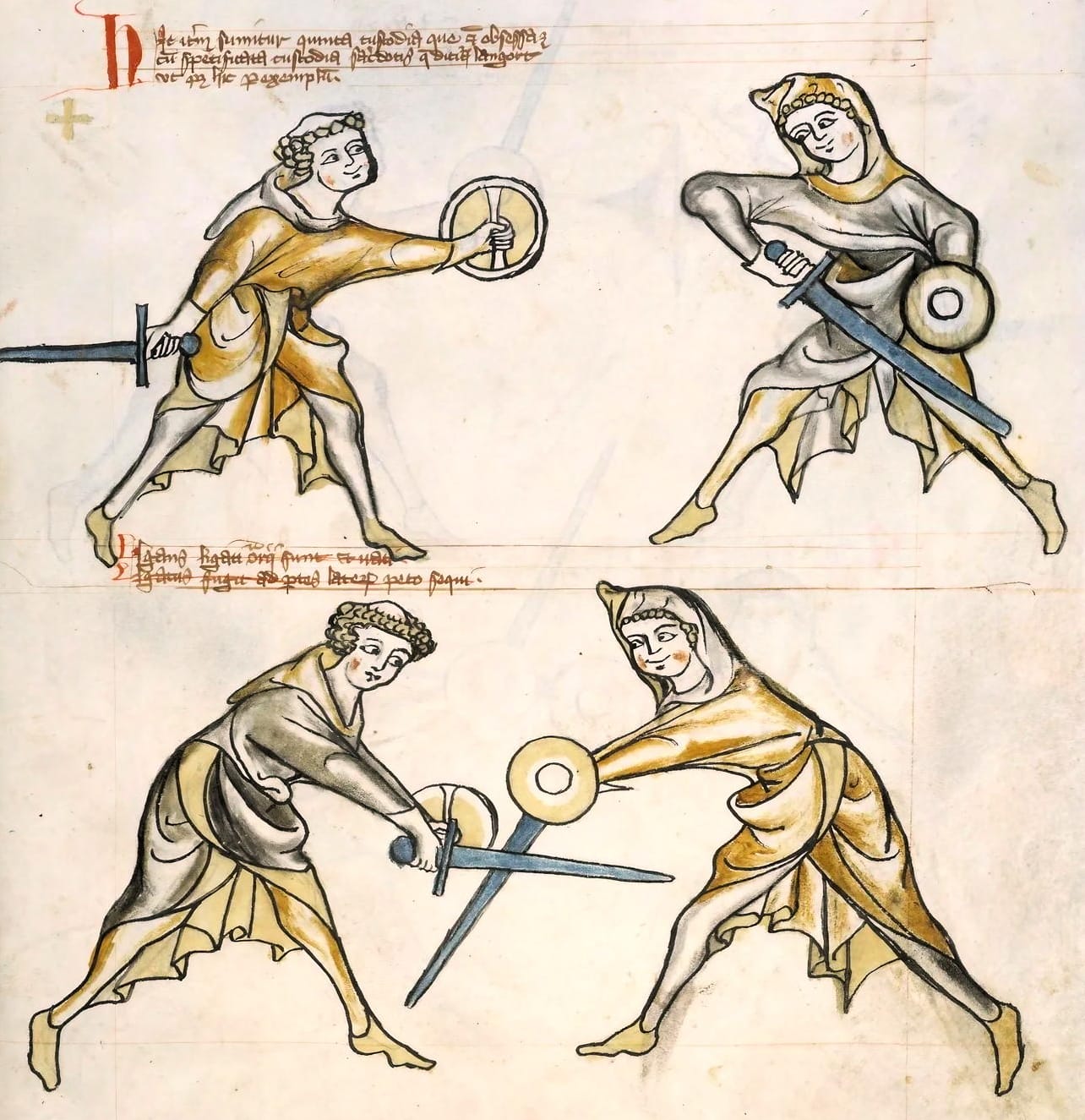

5. The first self-defense manual dates back to 1320 AD—the late-medieval period in Europe. Called a “fight book”—fechtbuch in German—it taught the form of sword fighting then popular for sport and for defense against real danger in public and in war. The combatants had no armor, so the “sword-and-buckler” technique emphasized defense and counter-attack. The sword’s edge was as deadly as its point. The buckler was a small shield for the left hand, usually positioned to protect the fighter’s sword hand and forearm. Once the fight began, the buckler was light enough to shift rapidly from one purpose to another in the flurry of combat.

The earliest sword-fighting manual (1320 AD) has 128 illustrations of sword-and-buckler technique. Most of the actions are shown in sequence, as here. The teacher is a tonsured priest (left); his student is on the right. In the top illustration, the combatants take up their Guard positions—the priest using what was called “Guard #5” and the student in the “Longpoint” position. As they engage, both adopt the standard use of the buckler to protect their sword hand and forearm. The student is successfully deflecting the priest’s sword. The manual recommends that he follow up by using the buckler in his left hand to “shield-strike” the priest’s buckler and sword aside while his right hand swipes his sword upward to the priest’s unprotected head. A Latin verse between the two illustrations reads: “The deflector and the deflected are opposed and angry; the deflected flees to the side; I pursue.”

The most treasured document at England’s Royal Armouries, the manual has attracted enormous interest, inspiring books and videos on how to use it as a martial arts guide. Everyone calls it by its shelf name: “I.33.” (Pronounced “one-thirty-three”—the first number is a Roman numeral one.) The 64-page parchment manuscript illustrates 36 combat sequences between two fighters, a priest and his student. How it works as a manual is described by its leading scholar this way:

More than anything else, I.33 documents an interpretive system that seeks to make combat intelligible. What I.33 teaches is not so much how to fight or train with a sword and buckler, as how to think about sword-and-buckler combat. Specifically, I.33 uses the tools of intellectual discourse to break down the dynamics of combat--in this case, the tools of late medieval scholasticism…. Its characteristic feature is reductive analysis, subdividing the subject matter into component elements (such as the schematised stages of each encounter), and… a simplified scheme of… structural elements (such as the seven basic guards)…. The chaotic process of combat is rationalised to resemble the structure of an academic disputation…. The author’s schematic model of combat is excellently packaged for expression through words and images.25Sophistication often comes early to weapons. The same goes for training in their use, as in this gorgeous manual.

6. Occasionally a manual comprehensively spells out the whole world of a particular subject—the context that surrounds it as well as the lore you need to execute it well. A tome published in 2019, titled Dry Stone Walls, is exemplary.

I once spent a couple of weeks in France supposedly learning how to build traditional dry stone walls. I would have done better with just this book. Far more than most manuals, it teaches the principles of the craft. A poem by Gary Snyder titled “Riprap,” begins:

Lay down these words Before your mind like rocks. placed solid, by hands26 Dry Stone Walls explains how “solid” actually works. Its principles apply metaphorically to anything that has to hold itself together—a poem, a theory, a software program.

In dry stone walling, the mortar that holds everything together better than mortar can is gravity plus friction. All the tricks of construction put gravity and friction to work. One principle states: “All stones are placed slightly sloping towards the inside of the wall.” Another declares: “Stones must touch all their neighbors and should not be able to move.”27

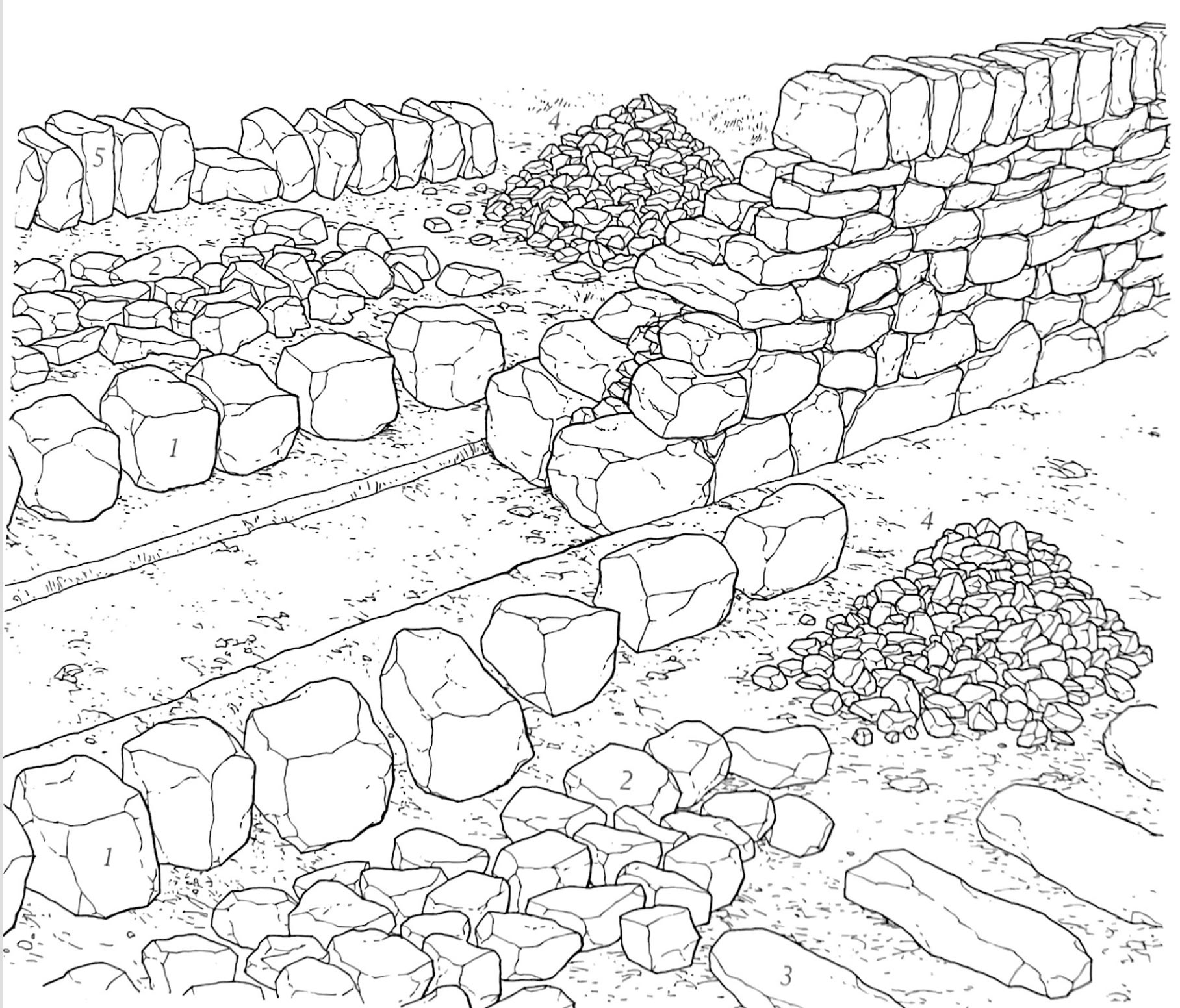

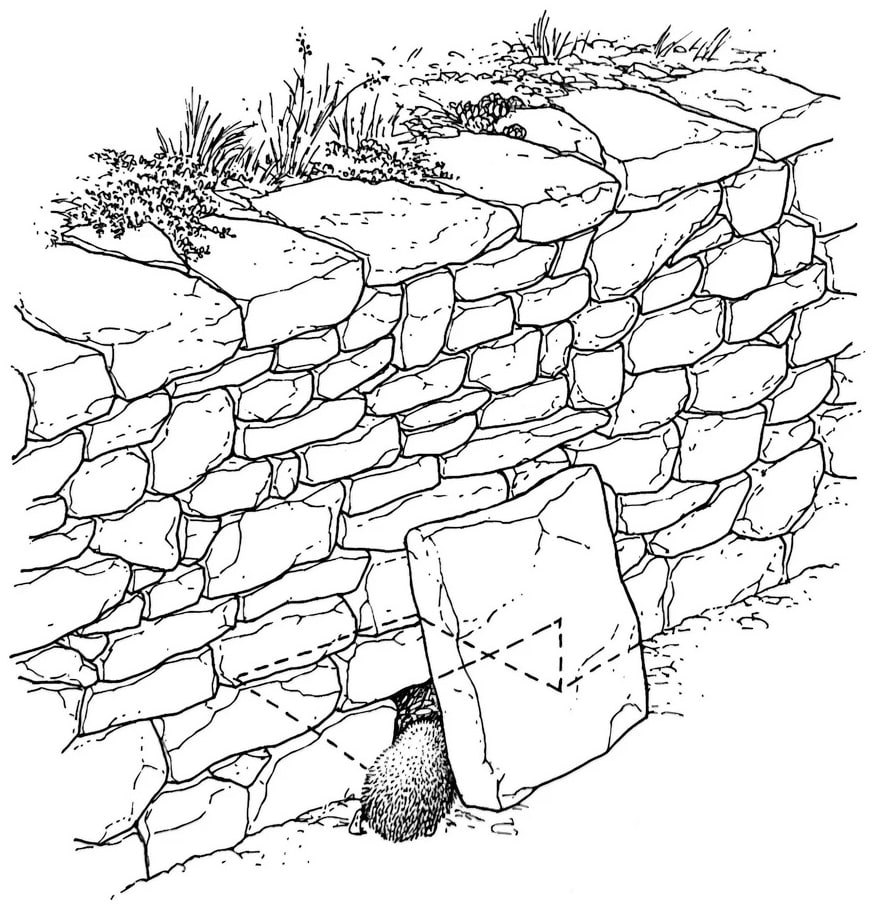

A dry stone wall needs five kinds of stones to ensure stability. Next to the foundation trench in this drawing, the largest are placed in the trench as foundation stones. Outside them on the ground are the many wall stones used for the facing. At the lower right are the throughstones that reach across the whole wall—there should be at least one every meter along the wall. The piles of small rocks are hearting stones, to be placed by hand inside the lower part of the wall. At the upper left are the cover stones that top off the wall.

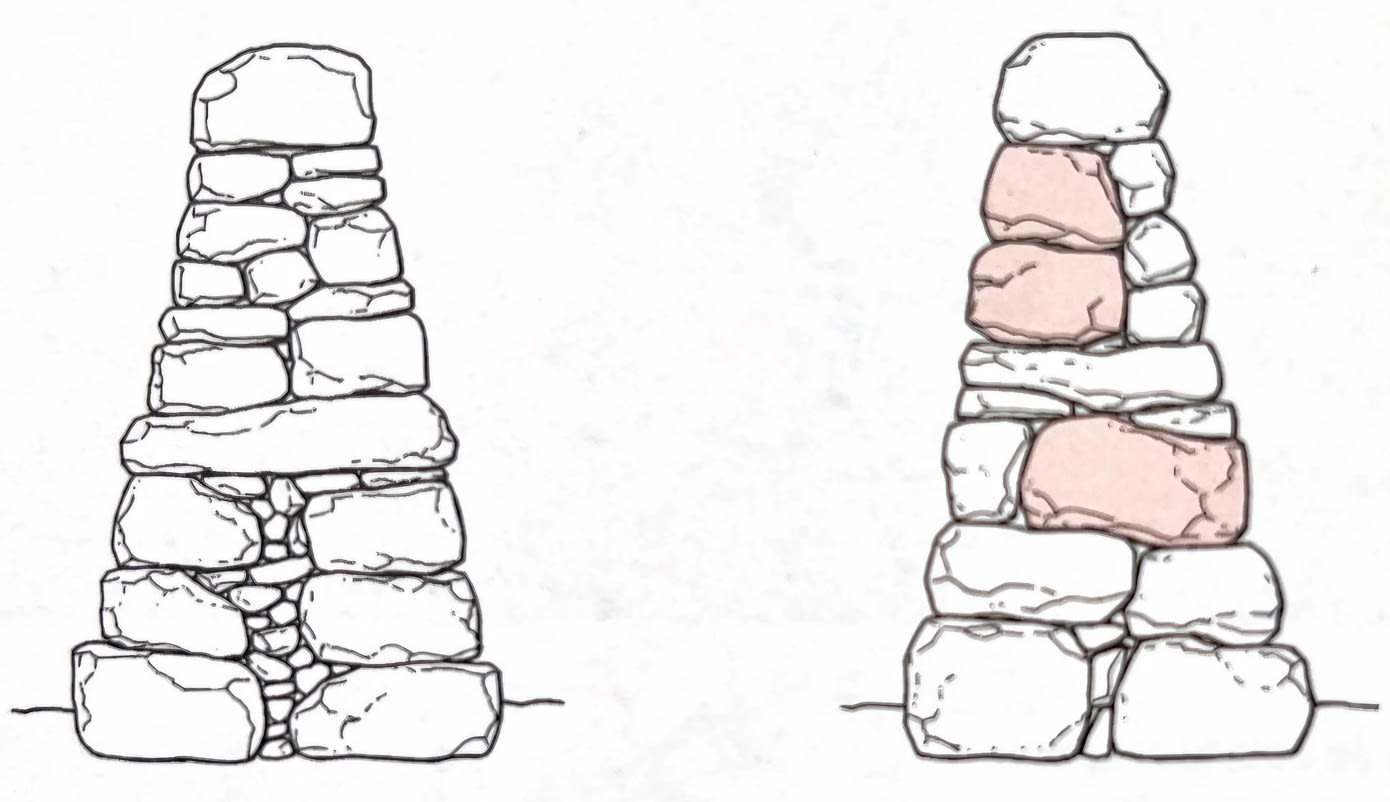

Correct stone placement is shown on the left--the largest stones are in the lower courses. In the right wall, the large pink stones are incorrect. Because they are misplaced too high, they extend too far across the wall, forcing their adjacent facing stones to be too shallow and thus insecure.

The gaps in dry stone walls provide habitat for local wildlife such as toads, snakes, lizards, insects, bats, and birds. You can welcome them with tailored openings in the sunlit side of the wall—here a den for a family of hedgehogs.

The best stones are big, wide, rough-surfaced, and somewhat rectangular (called “ashlar”). The proper technique is to always place “one stone on two, two stones on one” to ensure stability along the length of the wall. For cross-sectional stability, position each stone so that its long dimension reaches into the wall rather than along the outside, and include some “throughstones” extending all the way across the wall.

To ensure that each stone touches all its neighbors and is immovable, wedge-stones can be placed from inside the wall before the small “hearting” stones are poured in to fill the inner cavity. (Wedges placed on the outside will fall out.) With a hammer and chisel, you can level up the surfaces of irregular stones so they bed well with the stones around them.

Structured so, a seemingly inert wall actively defends its integrity for a long and useful life, exuding a geological-feeling permanence on the land. The book notes that:

Professionally built dry stone walls can exist for centuries without significant maintenance or repairs being necessary. However, often a certain degree of management is required because dry stone walls interact strongly with their environment.28 Sections of a stone wall can partially collapse over time due to subsiding soil, large animals, woody plant roots, reckless humans, or heavy machinery. As the book shows, repair is simple: just rebuild.

All the stones are right there in the grass.

On slopes, the foundation stones and lower stones are laid horizontally, like stair steps. This wall is in England’s Lake District National Park.

___________________________

[The next two Sections complete this Digression about MANUALS and YOUTUBE. First comes a Sub-digression--titled "Two Assault Rifles"-- concerning an irreverent manual that became obligatory for soldiers in the Vietnam War. The final Section of the Digression is "YouTube Rules."]