Unending World

WARNING: The section you're about to view is not a part of Chapter 3. It won't be a part of this book at all, but it is very much a part of the Book-in-Progress.

It is an illustrated short talk (17 minutes) on the subject of civilization. I gave it only twice. It belongs here in the online, in-progress version of Maintenance because it is, in effect, the larval stage of a chapter I will write many months from now, titled "Civilization." The talk explores a few ideas and images that are on my mind now and that I may use in the eventual chapter. The two audiences responded with enthusiasm and good suggestions, so now I'm trying it out on you--here in context of the rest of the book.

It's not a video, just written words and slides from my presentation. (As usual, you are invited to comment: On a computer screen, click "Make Comments" in the right margin, select some text, and write your comment in the box that opens, then click "Submit.")

NOTE: The high-resolution slides were selected and edited to be full of interesting details, so they are best viewed as large as your screen can handle. (On smartphones you can pinch into the images for the tasty details.)

--Stewart Brand

October 18, 2024

Unending World

I will focus on just two points. One looks into what it will take to mature from a global civilization to a planetary civilization—and why we need to.

* My other point concerns how we talk about civilization. The media are filled with statements like this from C-Span last week on Twitter—how AI might lead to human extinction.

Most of our talk about civilization is about how it will END, and how soon, and why, and who’s to blame. These days, everything the public frets about gets elevated to where it has to be seen as an “existential threat” to civilization.

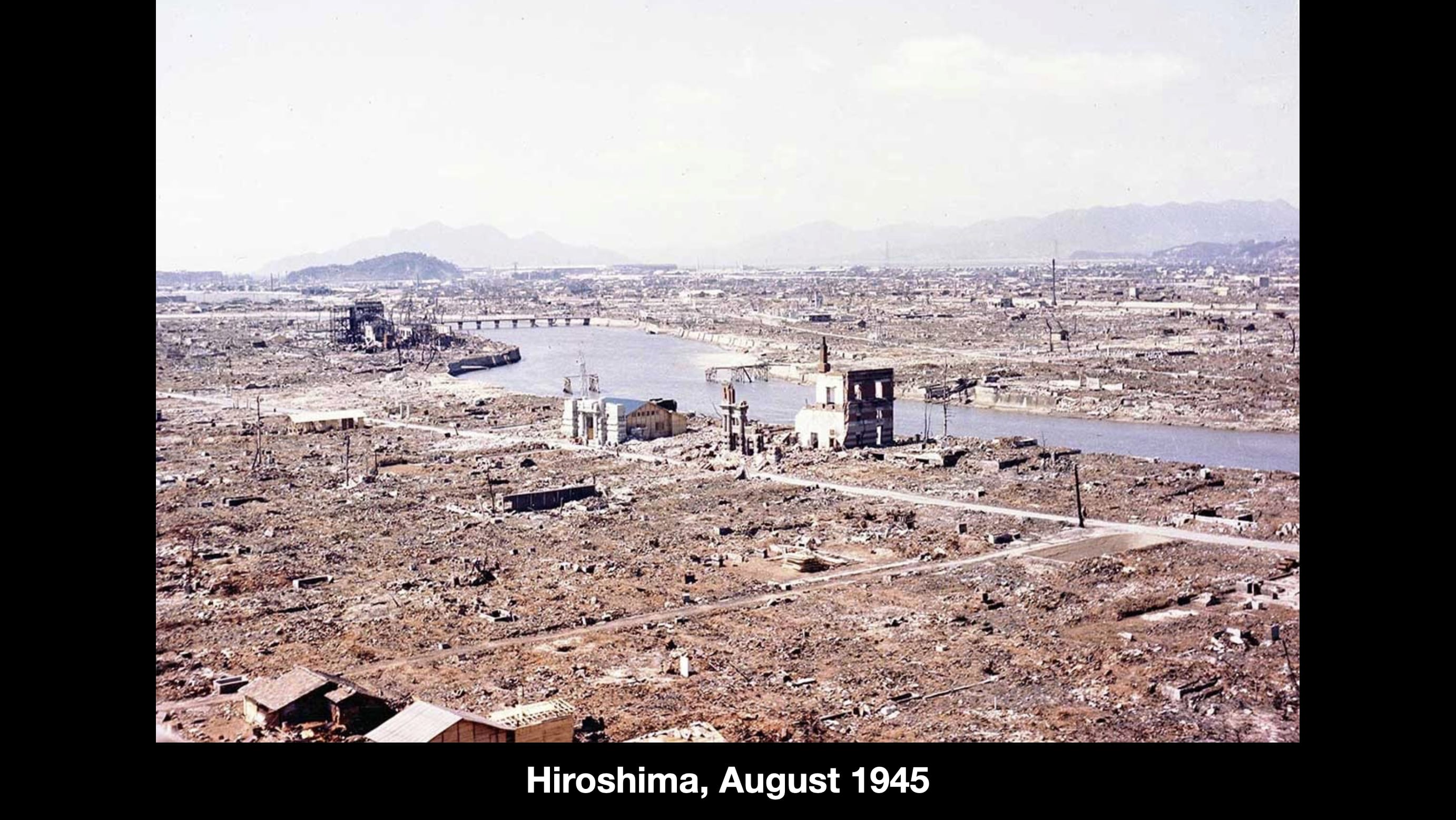

I think I know where that started, because I was seven in 1945 when the Japanese city of Hiroshima was destroyed by a single bomb.

Hiroshima and then the Cold War introduced a new idea to humanity—that we had the power to destroy the world.

My youth was poisoned at times by that dread.

* For the first time, all of human civilization had a shared image to think about itself with, and it was this:

The mushroom cloud. This was the way humanity thought about its power and its prospects.

* Just 23 years later that image was replaced by a more upbeat one. Shot with a camera by a human orbiting the Moon.

It’s interesting to note that in that photo there’s no sign that Earth has a civilization on it.

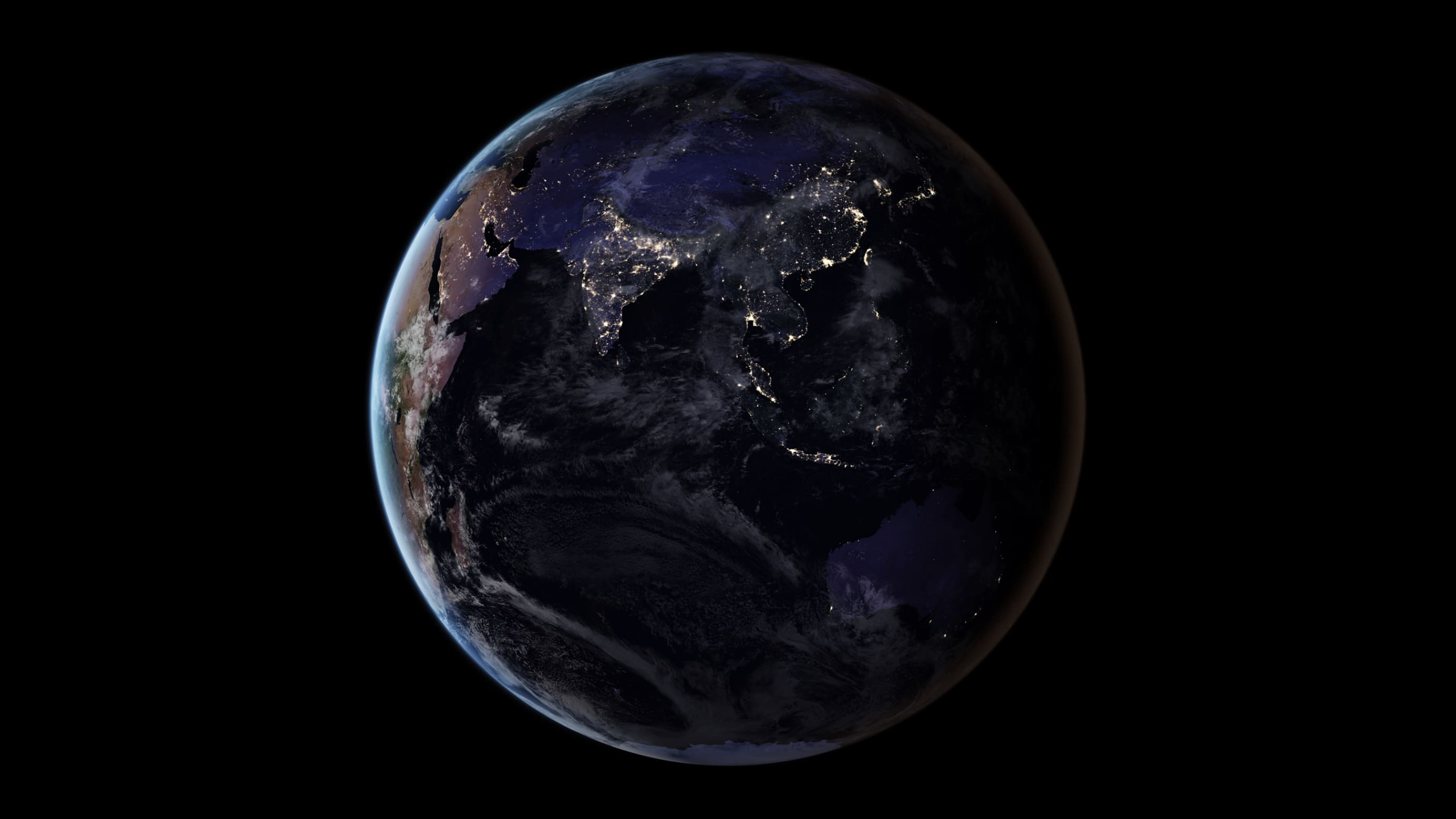

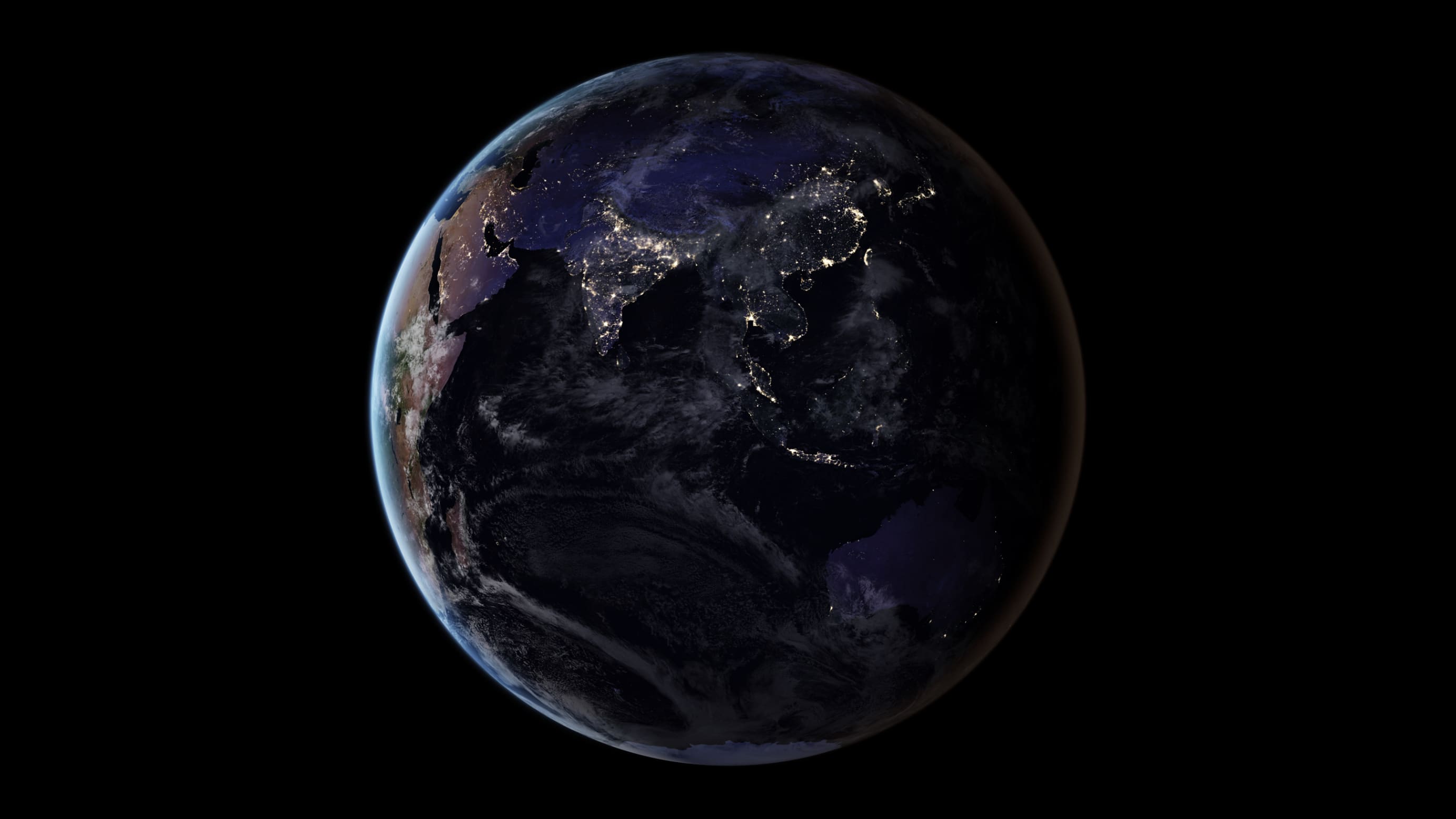

* We’re only detectable when you look at Earth’s shadow side, like this:

That’s the real self-portrait of civilization.

* Mostly, we still think of Earth in global terms—nations on continents—and the power relations between those various patches.

* But the planetary reality keeps leaking through, especially in light of climate change, which is not a global issue. It is a planetary one.

* That image is wholesome and helpful, and yet the old dread keeps poisoning everything that we think about in a big way.

And the dread is harmful. It fosters helplessness.

It makes us fear the future and fear everything deeply new.

And it is grossly exaggerated.

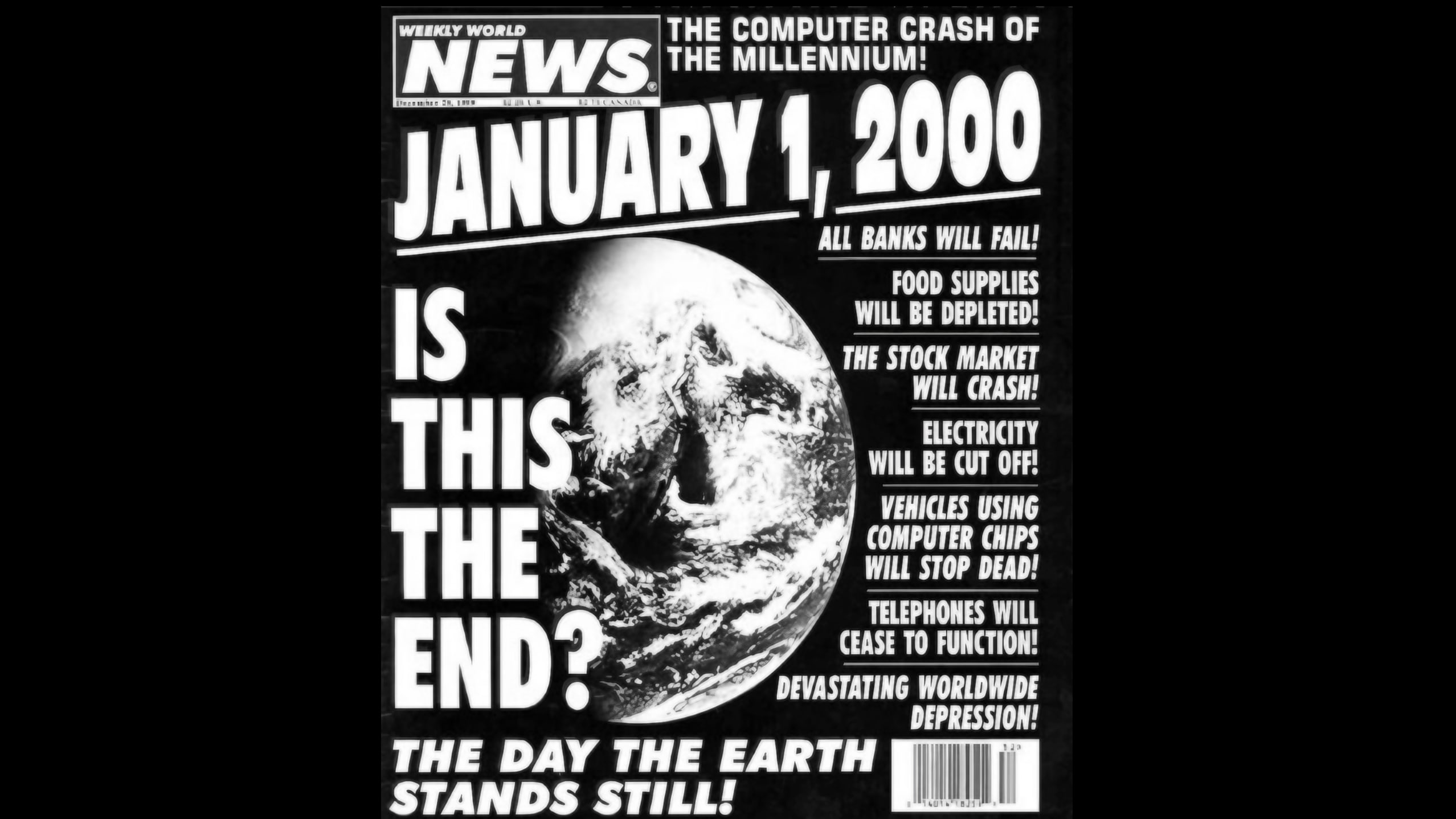

* We even worry about things that turn out to be imaginary, like the Y2K problem.

It was treated as an existential threat, and it was nothing. But that didn’t stop us.

Mass extinction?

Existential threat!

Climate change?

Existential threat!

Artificial intelligence?

Existential threat!

* When you have a bunch of things all threatening to end civilization, people start adding up risk percentages, and they don’t see how we can survive this century.

What if none of these things would end civilization?

* Let’s go back to the root of it all—Hiroshima in the summer of 1945 looked like this.

Five square miles destroyed by a firestorm. 75,000 people dead. The bomb that did it was unique, but the effect was not—not that summer in Japan.

* This was Tokyo earlier that year, utterly destroyed by tons of conventional incendiary bombs dropped by American B-29s. 16 square miles burnt to ashes. 83,000 died in the firestorm.

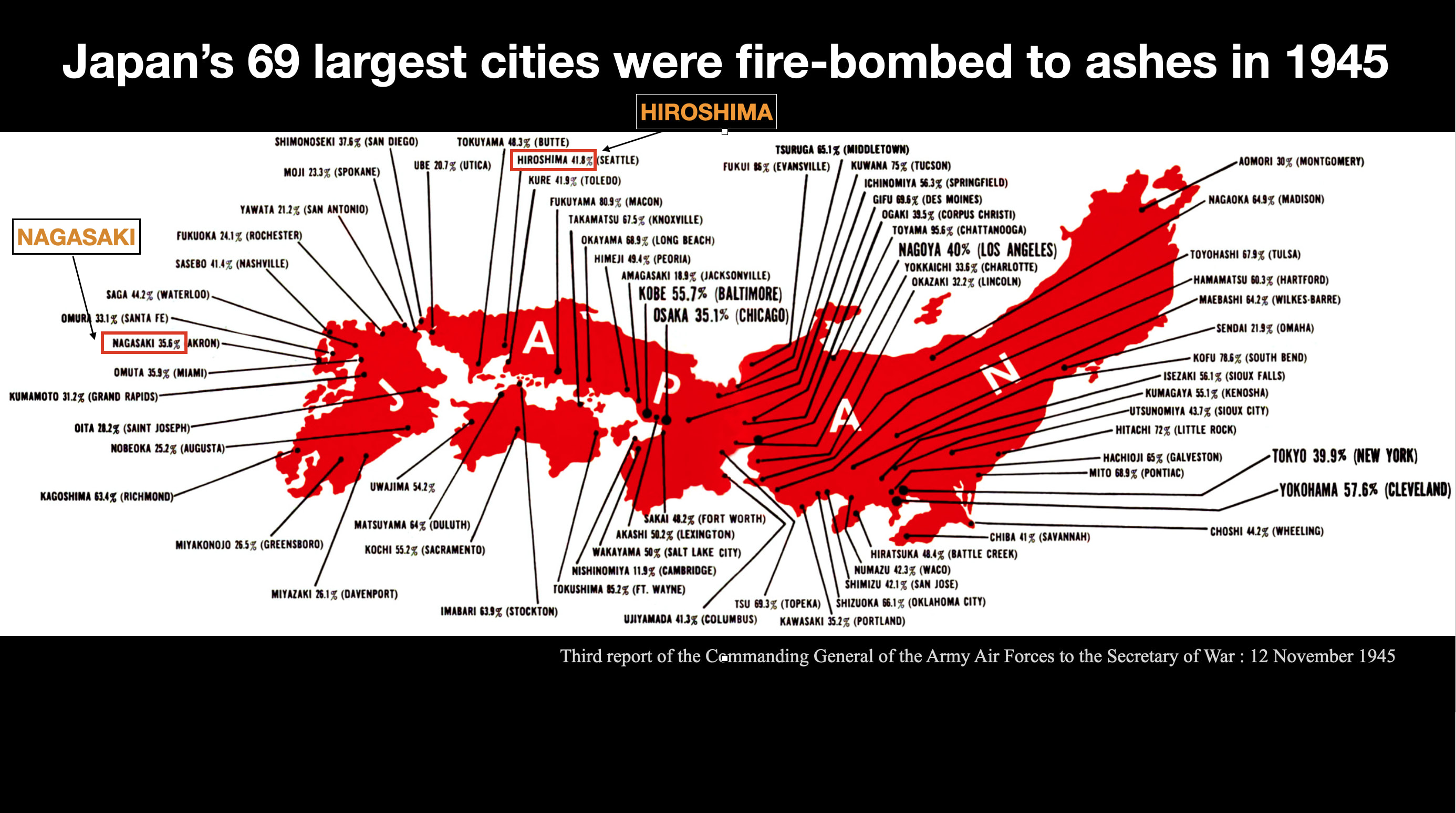

* Most of the cities in Japan—69 of them—were firebombed by us that year.

Atomic bombs are basically incendiary weapons, so the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki blended in with the rest of our incineration of Japan’s cities.

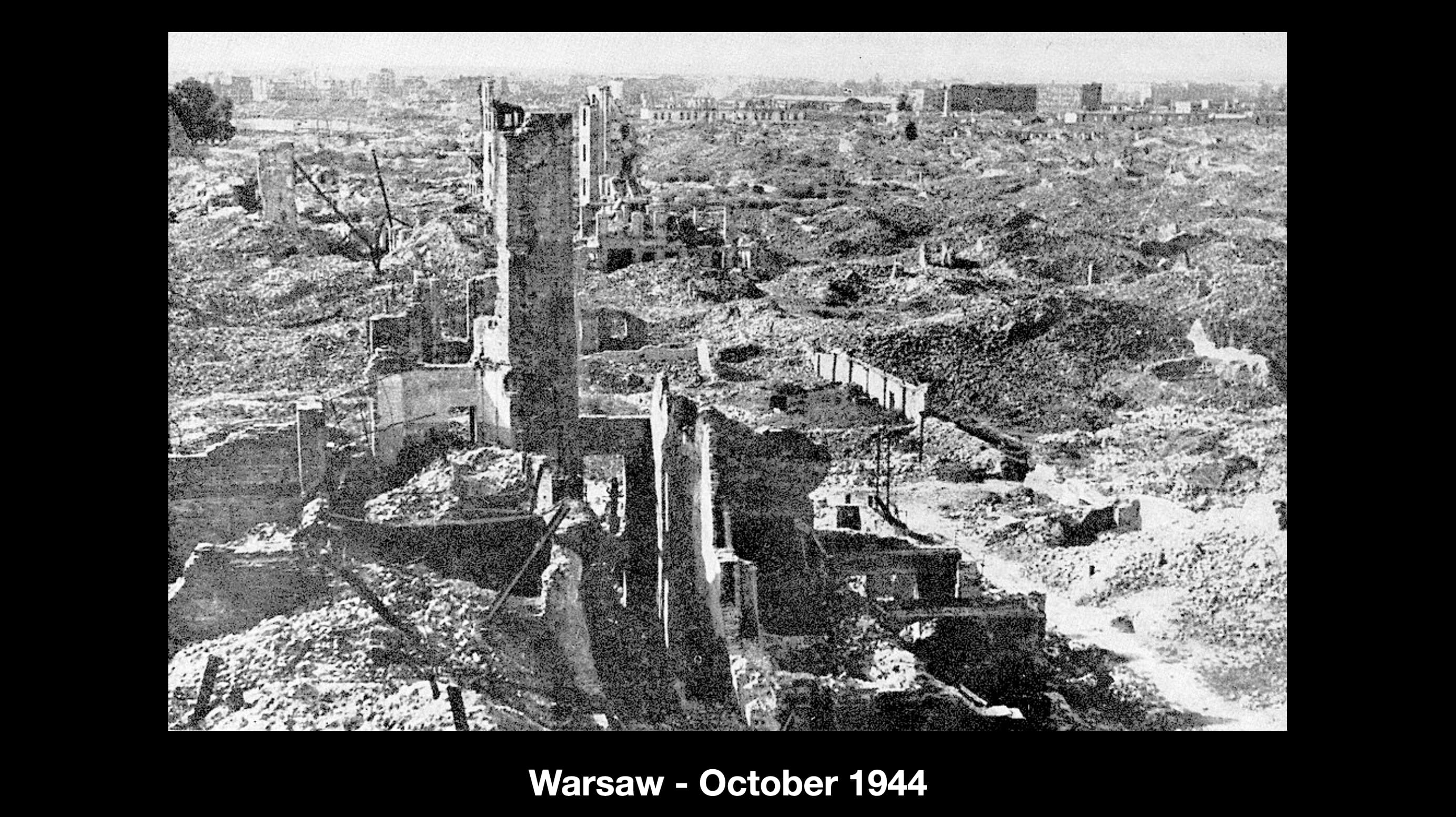

* Many European cities looked exactly the same that year.

This is Warsaw after the Germans bombed it—25,000 died in the firestorm.

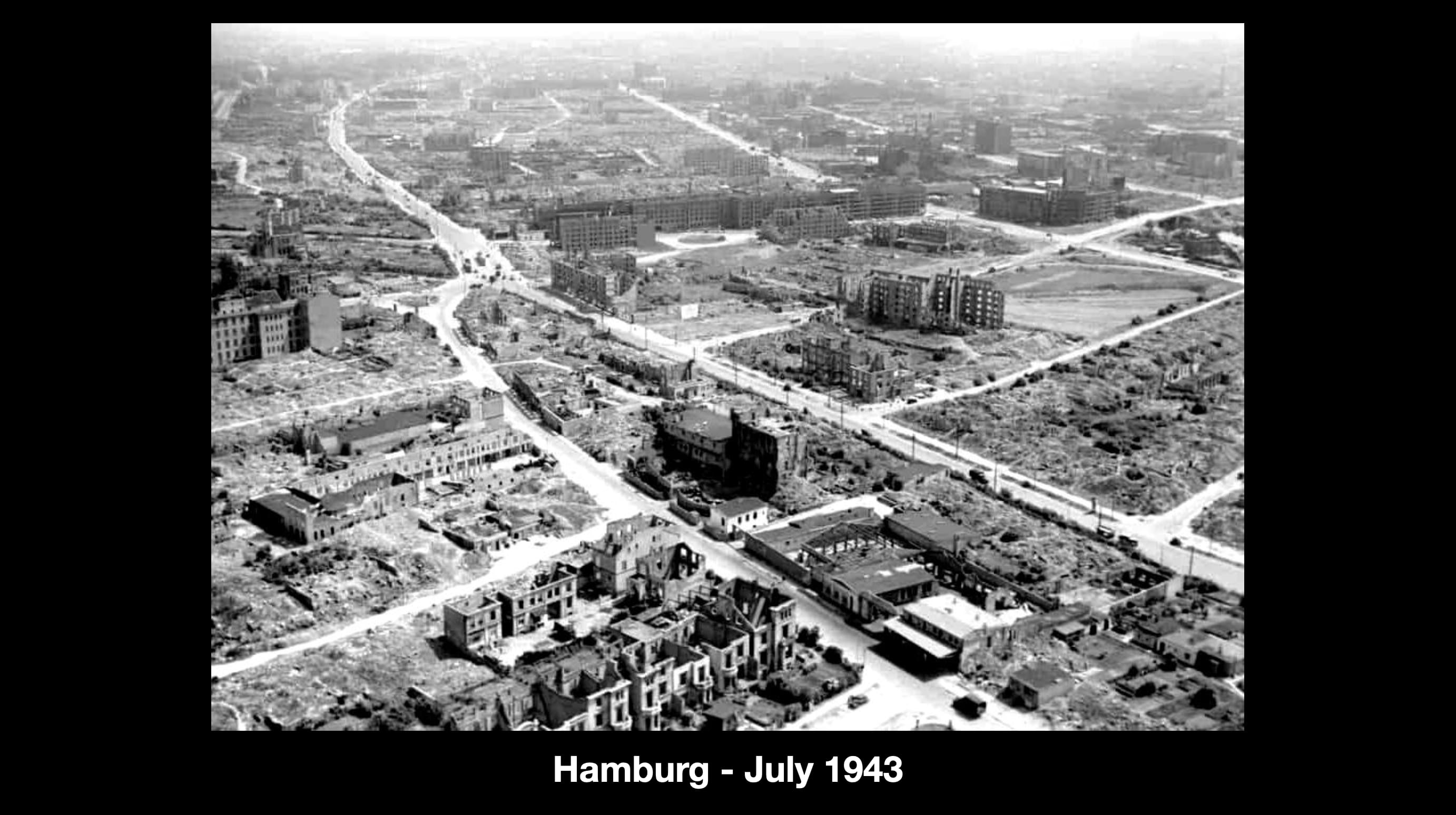

* Hamburg after the Americans bombed it. 37,000 died in the firestorm.

* Dresden after the British bombed it—25,000 died in the firestorm. And so on throughout Europe.

I wonder if we drew the wrong lesson from World War Two. Look:

* Here’s Dresden now.

* Hamburg now:

* Warsaw now.

* Tokyo now is the largest metropolitan economy in the world.

* And Hiroshima now.

Just two months after the bomb, John Hersey reported, “The survivors are mostly back at work. The city is reborn as a community.”

The real lesson from World War Two is that civilization bounces back, even from utter devastation.

Cities are the most durable thing humans make.

A massive nuclear war now would be horrible. World War Two taught us how horrible it can be. It taught us that civilization would be traumatized… and then it would rise from the ashes.

Nuclear war now would not make civilization cease to exist.

Neither will mass extinction or climate change or artificial intelligence, serious as they are. In the coming decades, there will certainly be various kinds of calamities, and we will keep on surviving them and learning from them.

Our planet has been through a lot, yet Earth abides.

Humanity has been through a lot, yet we abide.

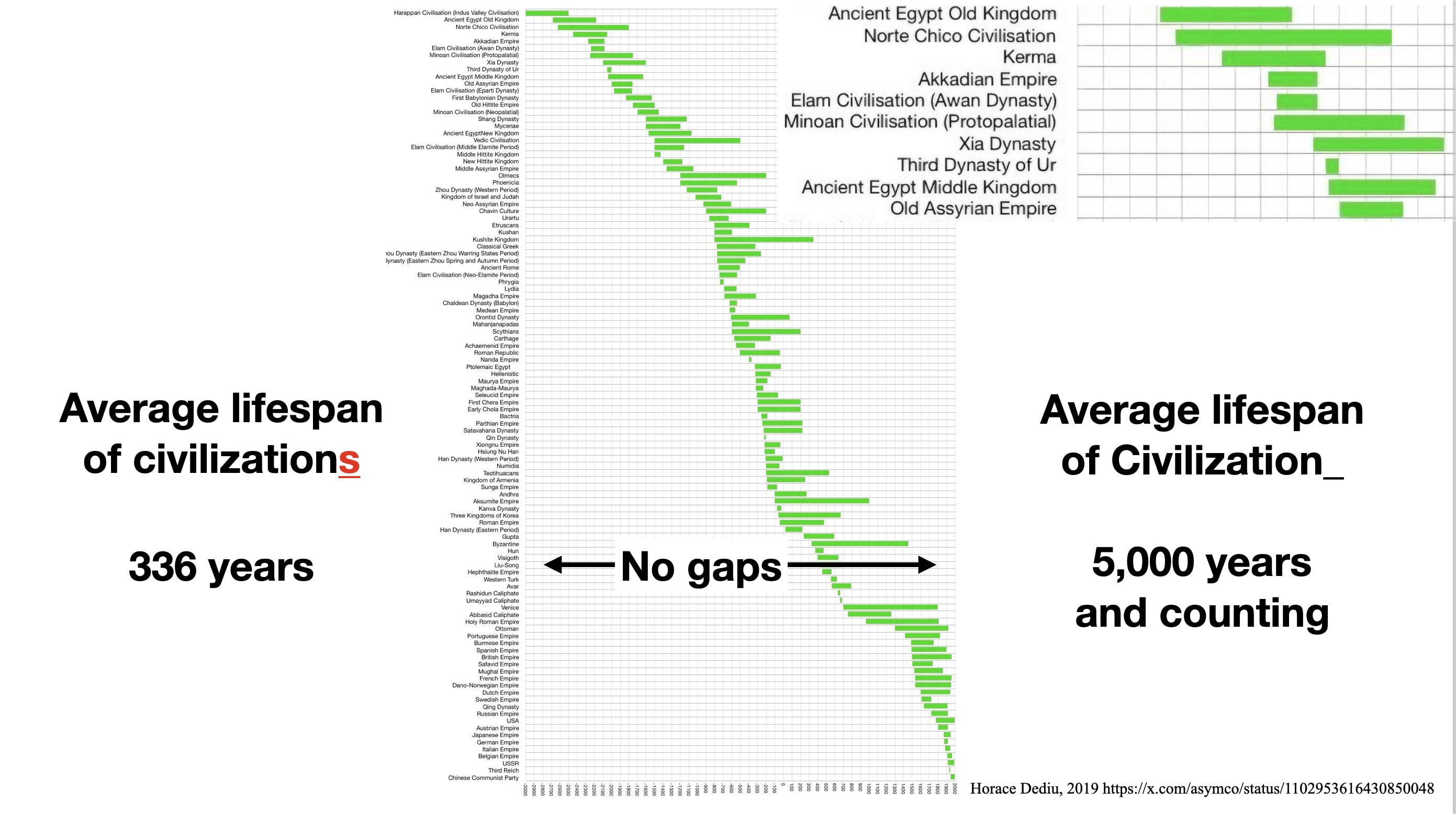

* Wait a minute. Civilizations die all the time. Here’s a tally of the world’s 109 major regimes in the last 5,000 years and their lifespans.

The squares in each row represent 100 years. Clearly, regimes are eventually fragile.

But notice there’s not a single gap.

Civilization as a human practice has carried on steadily, progressively, in a variety of forms, ever since the first cities.

Civilizations come and go. Civilization continues.

* But what about now, when we have a global civilization, with no backup?

Does history show it will be fragile? Or robust?

Many think that global civilization must be fragile—because it is so complex.

I think our civilization is in fact robust because it is so complex. And it is made of many different societies, each capable of flourishing alone.

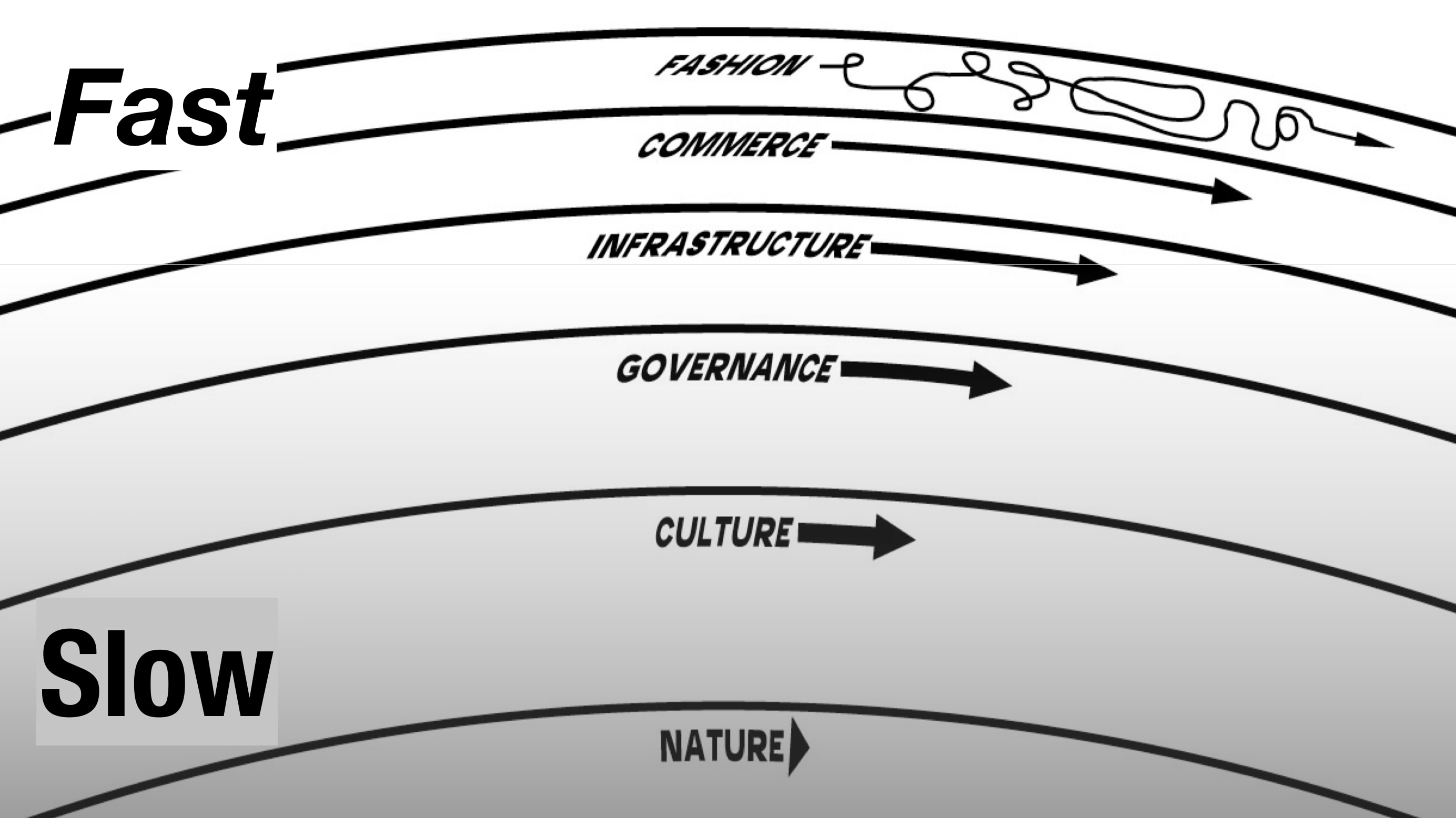

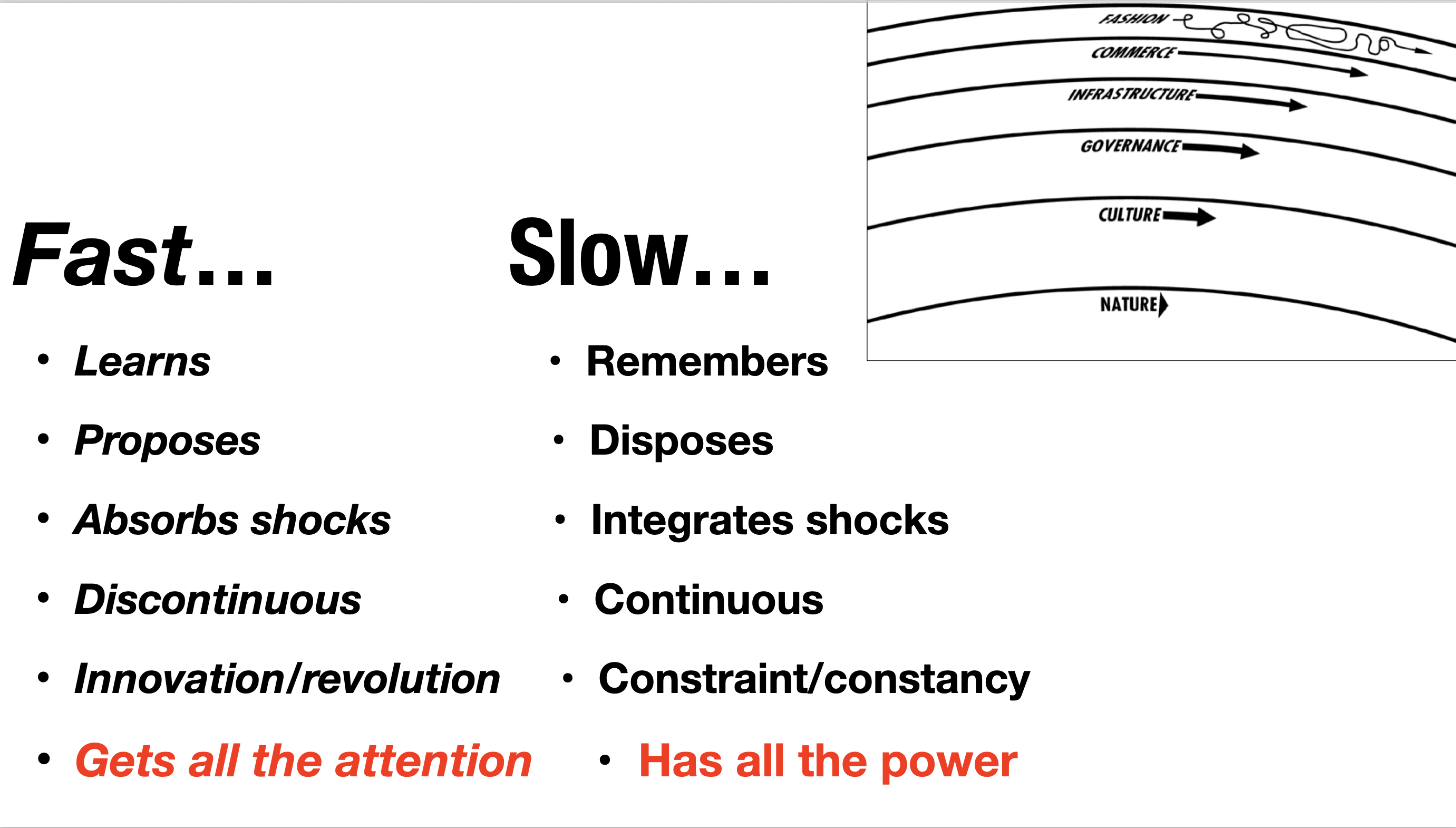

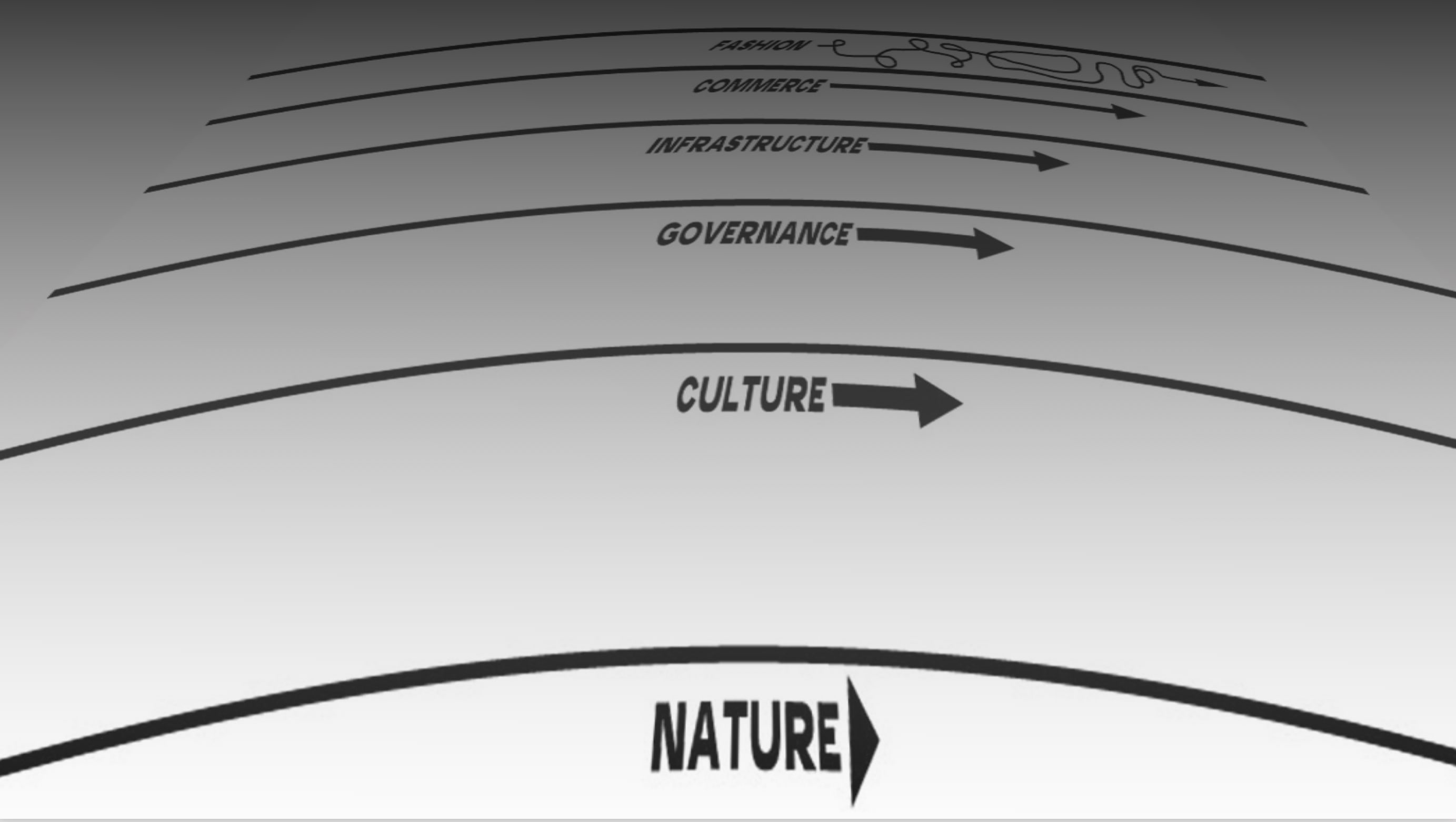

* I think I can explain something about how the complexity works with a diagram.

It is a cross-section of a healthy civilization in terms of pace layers of change.

In this diagram, the rapid parts of a civilization are at the top, the slowest parts at the bottom. Fashion changes weekly. Culture takes decades or centuries to budge at all.

These layers are what enable a civilization to learn and adapt—and keep learning and adapting.

* It’s the combination of fast and slow that makes the whole system resilient.

Fast learns, slow remembers.

Fast proposes, slow disposes.

Fast absorbs shocks, slow integrates shocks.

Fast is discontinuous, slow continuous.

Fast affects slow with accrued innovation and occasional revolution. Slow controls fast with constraint and constancy.

Fast gets all the attention. Slow has all the power.

* Where slow has all the power, making any change takes a lot of time and diligence. If you want to do lasting good, this is the perspective to keep in mind.

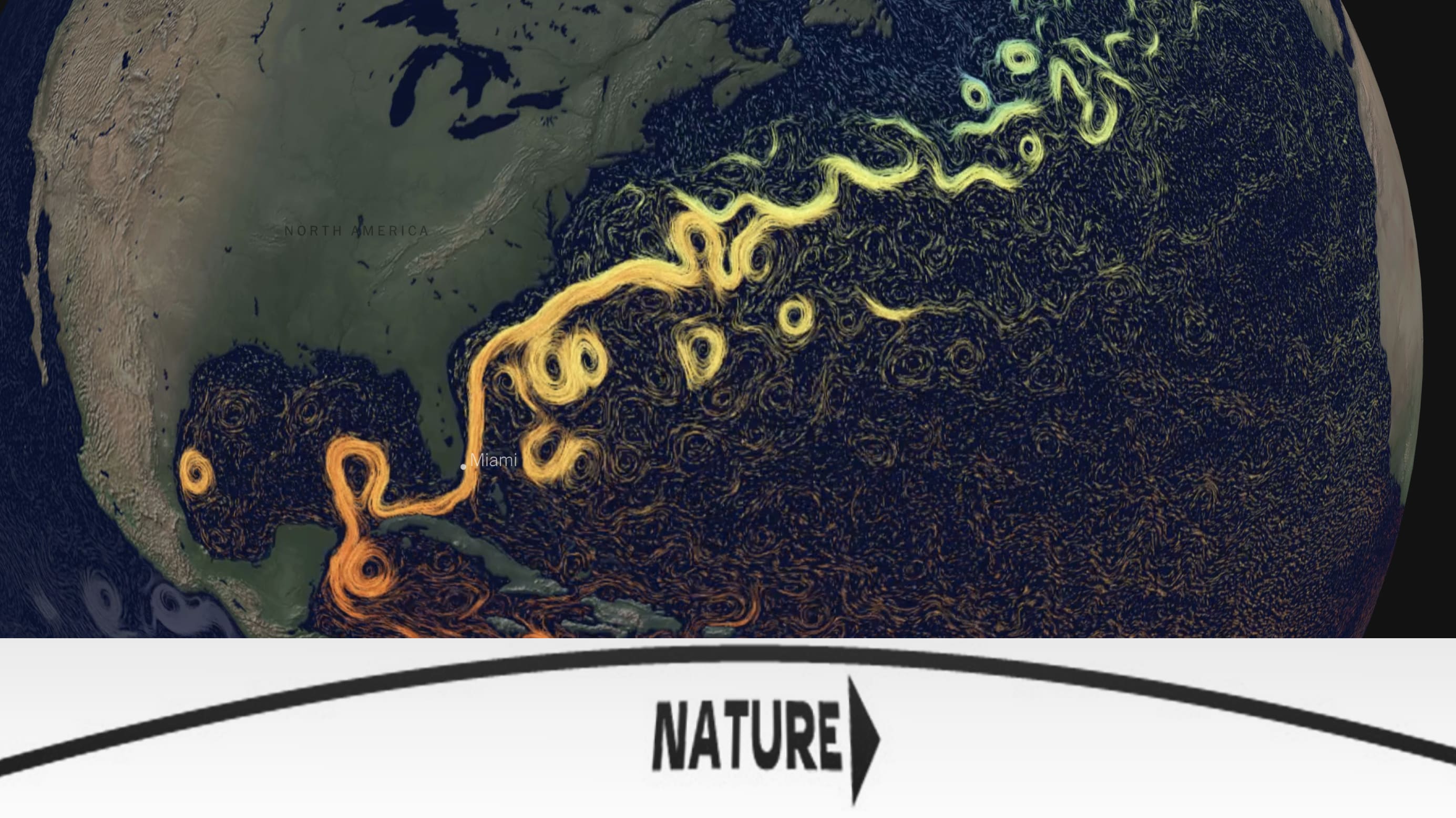

* That brings us to Nature.

This is the Gulf Stream. It carries tropical water north in the Atlantic and keeps Europe warm. But climate change is melting so much Arctic ice, fresh water is slowing the flow. If the Gulf Stream stops, Europe will freeze.

That might be one of the calamities in this century.

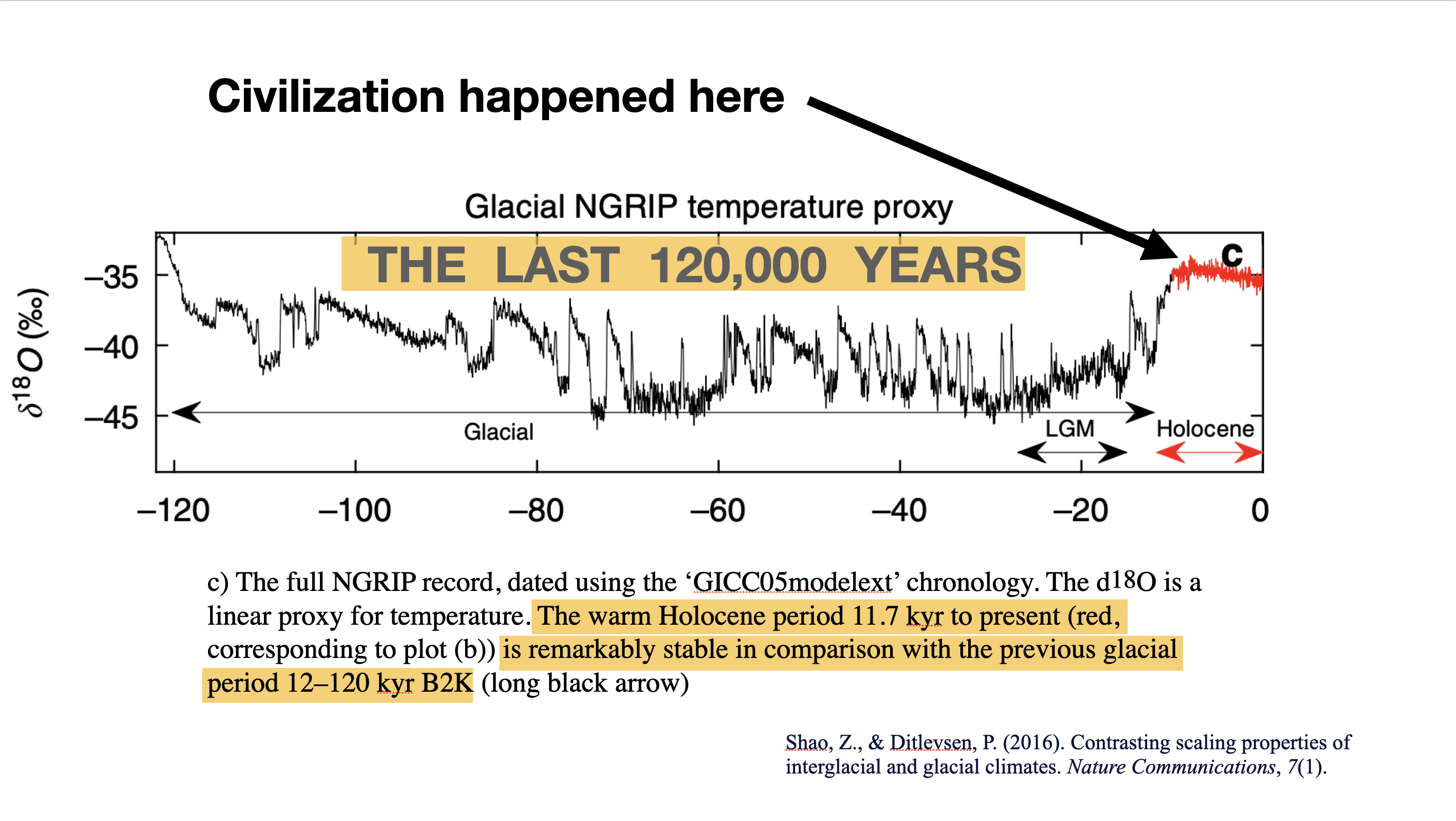

* Most of the time climate is extremely variable.

But 10,000 years ago, it suddenly settled down into a highly stable climate that happened to be ideal for agriculture and civilization. And it stayed that way till now.

That’s the Holocene.

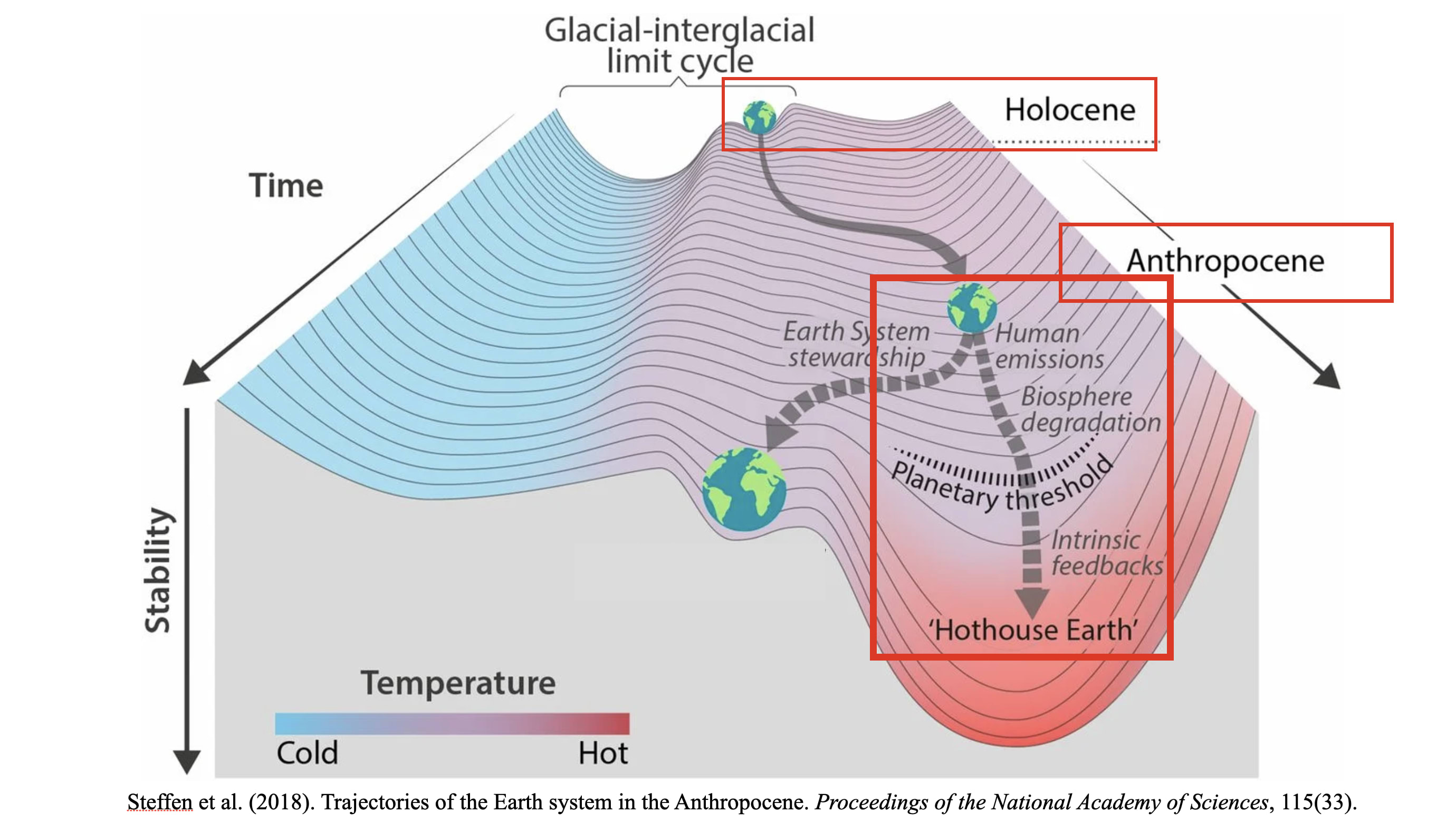

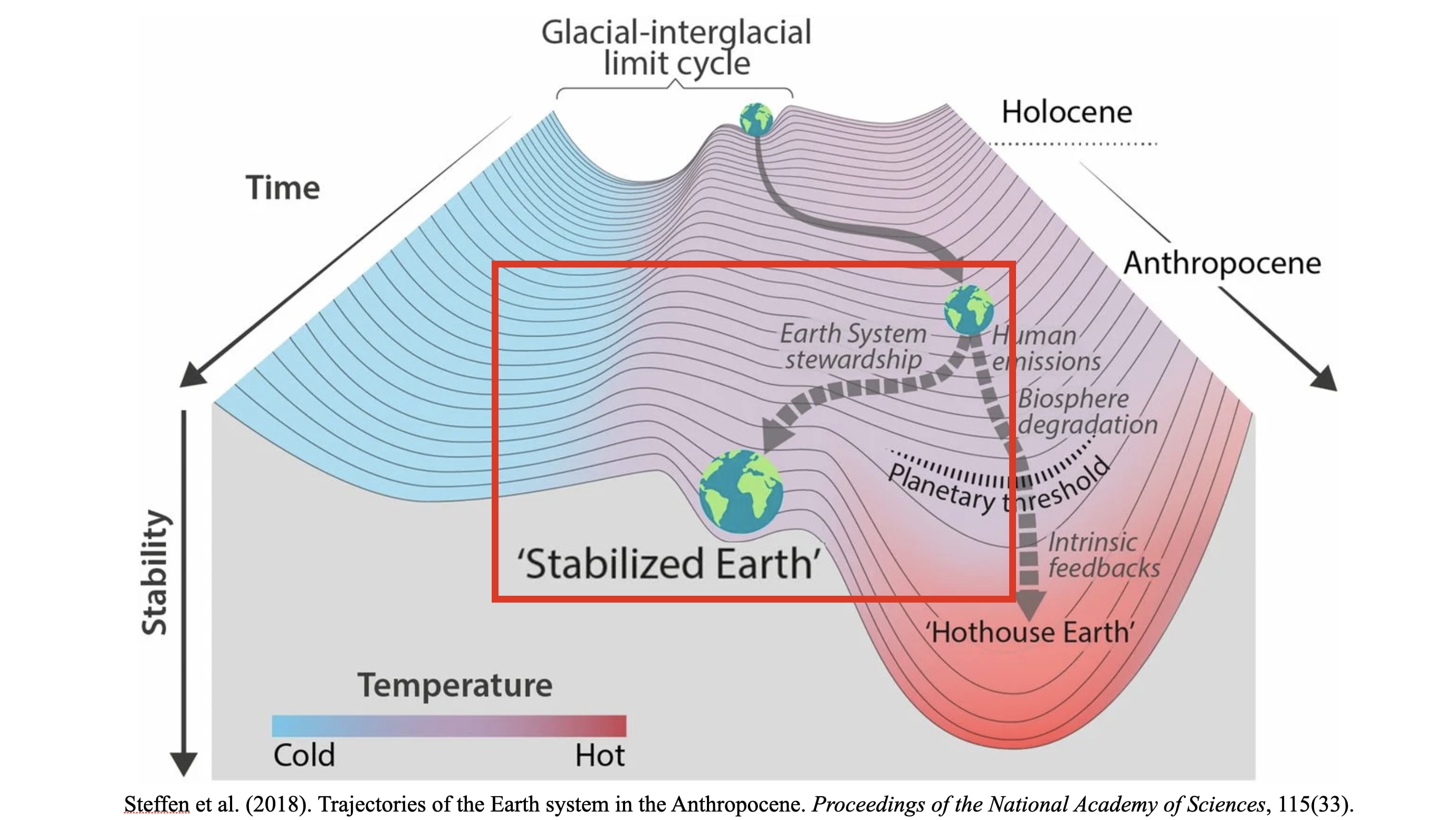

* Now we’re in the Anthropocene, with massive climate influence by humans.

We have planetary agency—and wish we didn’t. Gaia, we realize, was doing fine until we fell in love with combustion.

What we want is for the Anthropocene to be an endless Holocene.

We already have a global civilization—with a global economy and global infrastructure.

* Now, because of climate-scale problems that we caused —and must solve at scale—our task in this century is to become a planetary civilization—one that can deal with climate in its own terms.

We may have a thriving global economy, but there’s no such thing as a “planetary economy”—the dynamics in play aren’t measured that way.

We have to integrate our considerable complexity with the even greater complexity of Earth’s natural systems so that both can prosper over time as one thriving planetary system.

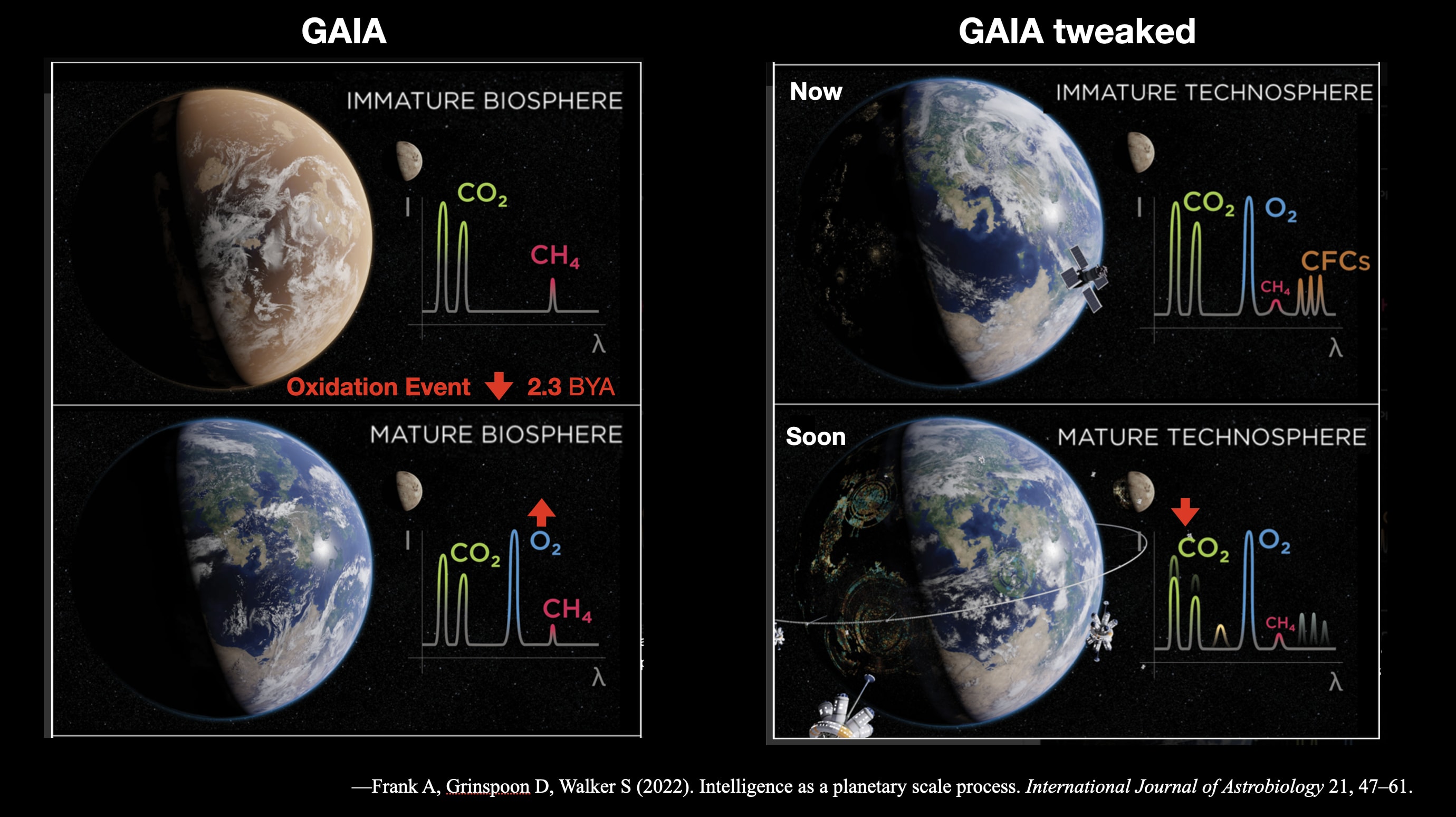

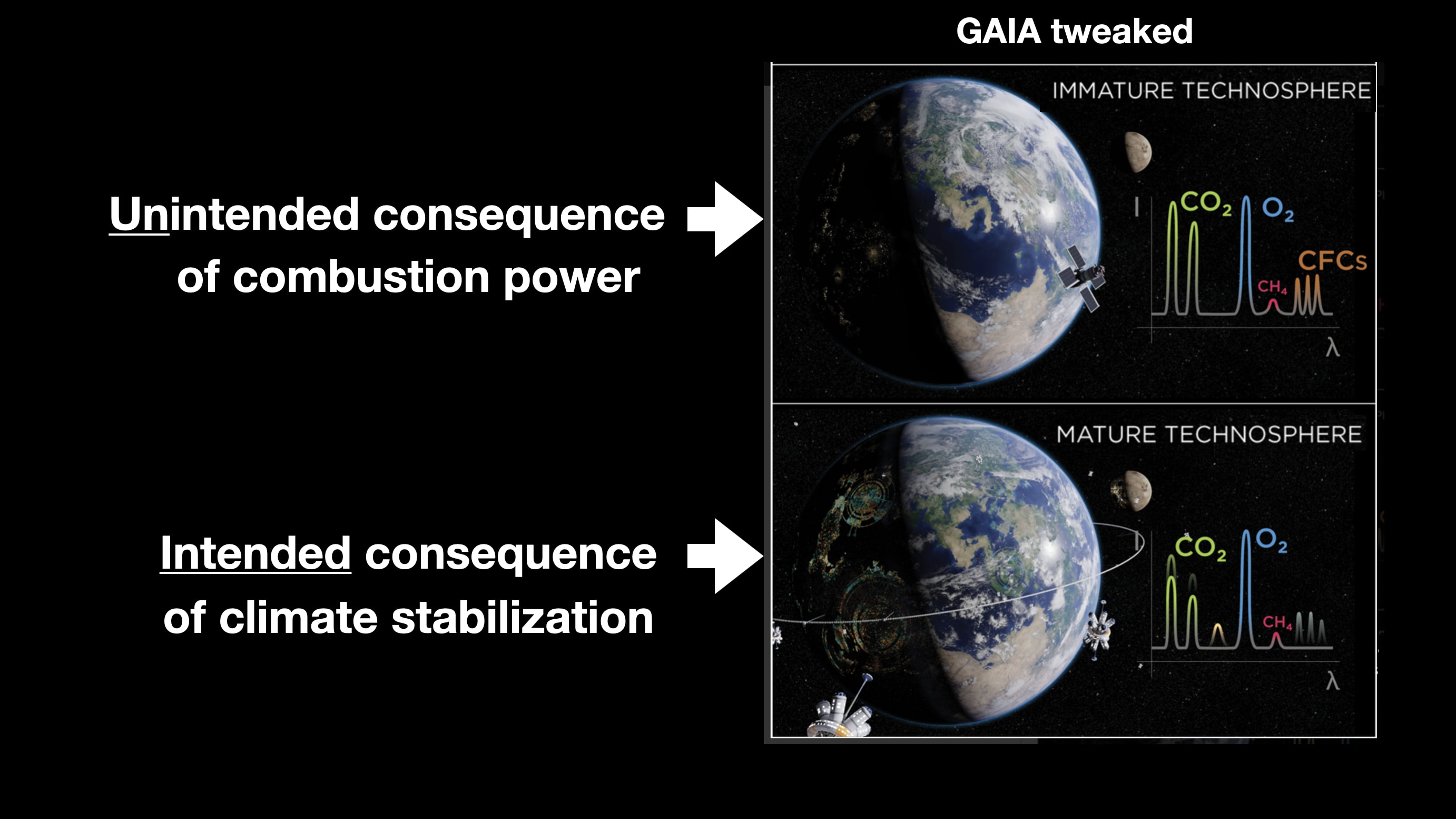

* Here’s the sequence in Gaian terms. Earth’s early anaerobic biosphere had an atmosphere with no oxygen and not much life. After the Great Oxidation Event 2.3 billion years ago put vast quantities of reactive oxygen into the atmosphere, aerobic life expanded, diversified, and took over the planet.

It created us.

Fast-forward to the present—to what Adam Frank and David Grinspoon call the “Immature Technosphere”—with its excess of carbon dioxide and chlorofluorocarbons destabilizing the climate.

Global civilization made that happen.

A planetary civilization can undo the effect and get us to a “Mature technosphere”—where carbon-dioxide falls back to previous levels and climate stability returns.

One proof we can do it is the fact that we’ve already succeeded in protecting the planet from other Gaia-scale threats.

* Being smarter than dinosaurs, we have figured out how to detect potentially dangerous asteroids and deflect them.

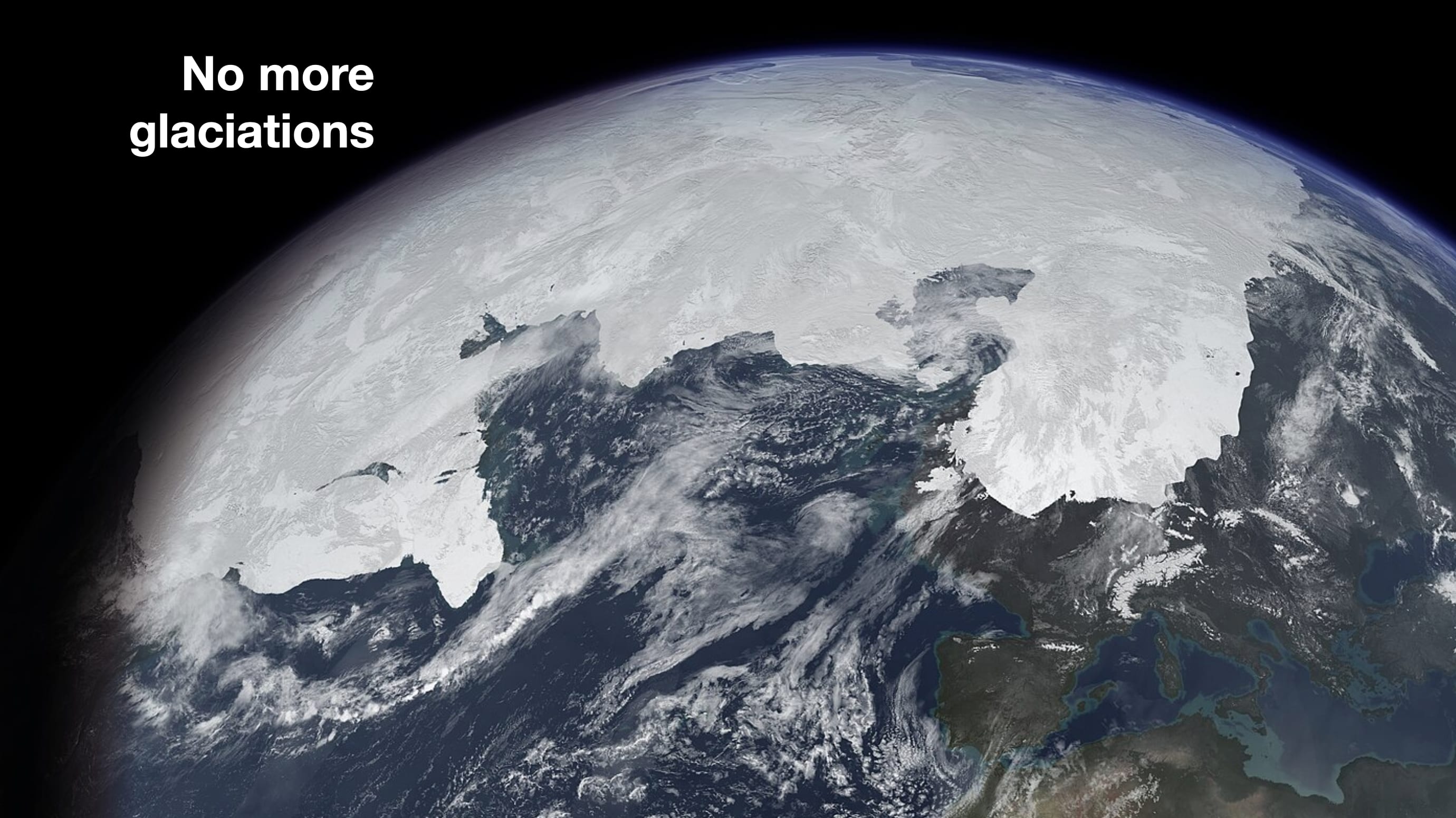

What about ice ages? Our current interglacial period is already overdue for the next massive glaciation.

* But it’s not going to happen, and it may never happen again. Accidentally we’ve created an atmosphere that can no longer cool drastically unless we tell it to.

The goal is this: We want to ensure our own continuity by blending in better with Earth’s continuity.

How do we do that?

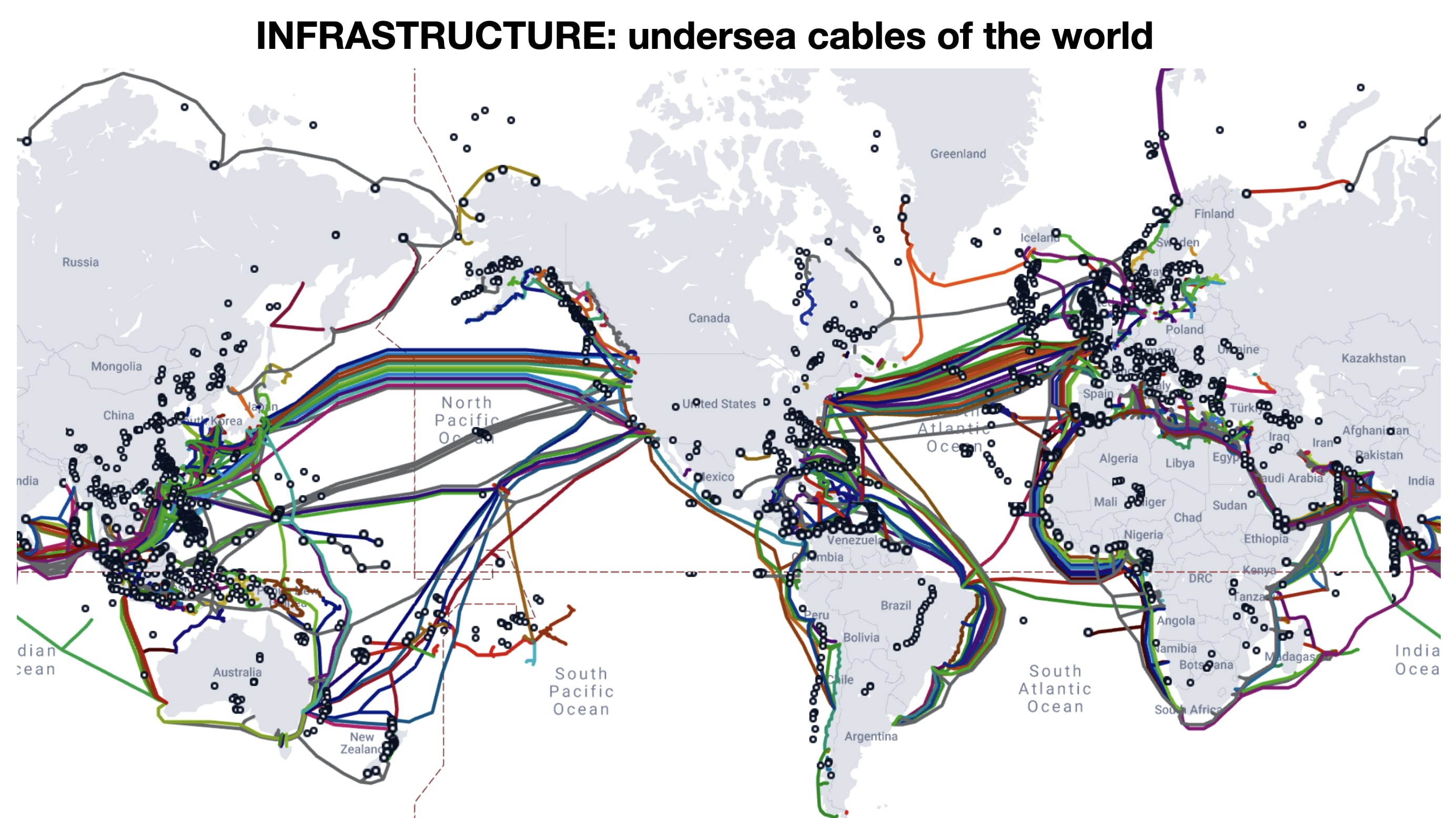

* Here’s one suggestion: Expand how we think about infrastructure.

We’ve gotten very good at funding, building, and maintaining global infrastructure—such as the world’s undersea cables.

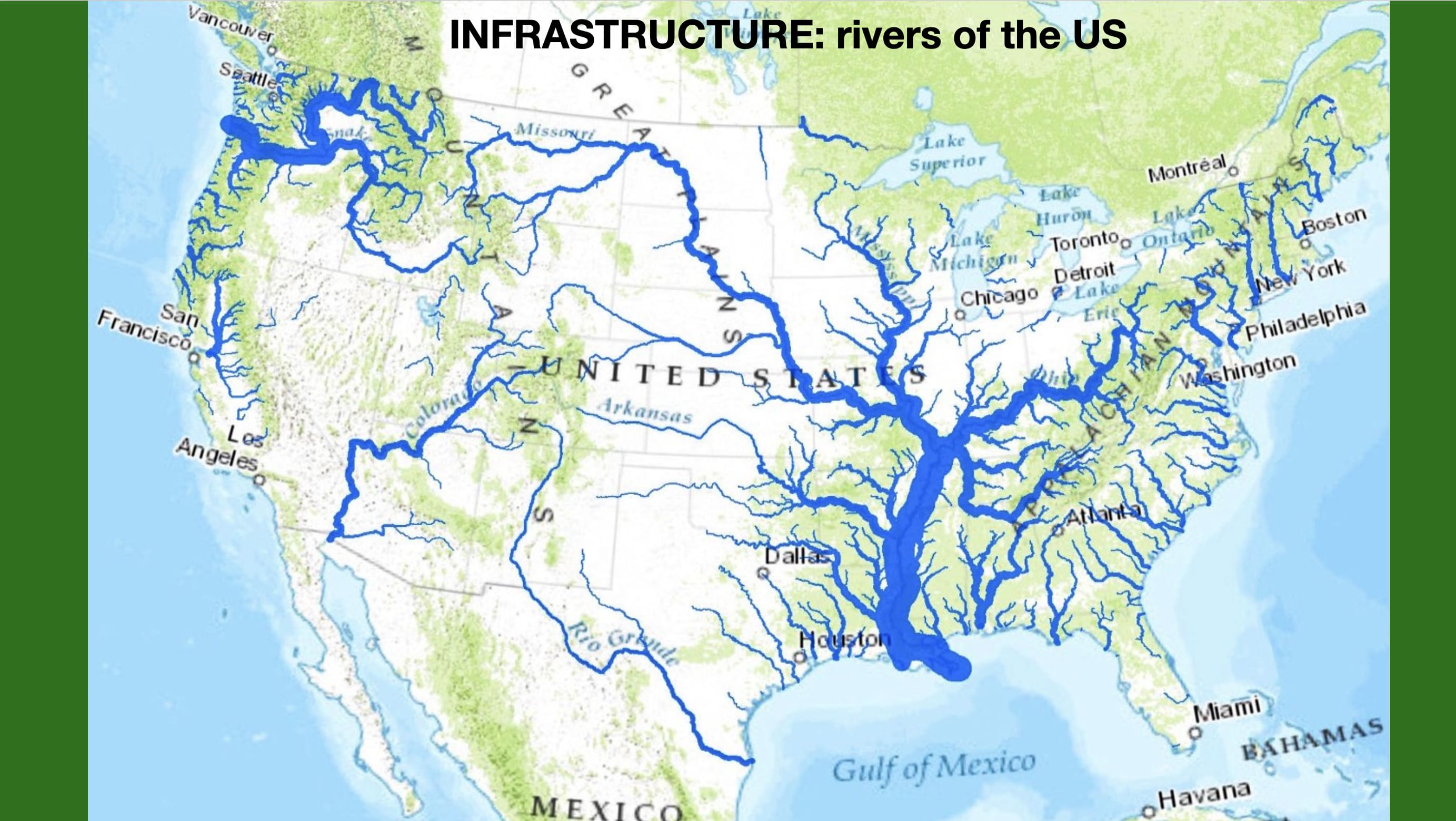

* That experience should make it easy for us to understand the role of natural infrastructure and make the effort to maintain and sometimes enhance it.

We already treat rivers that way.

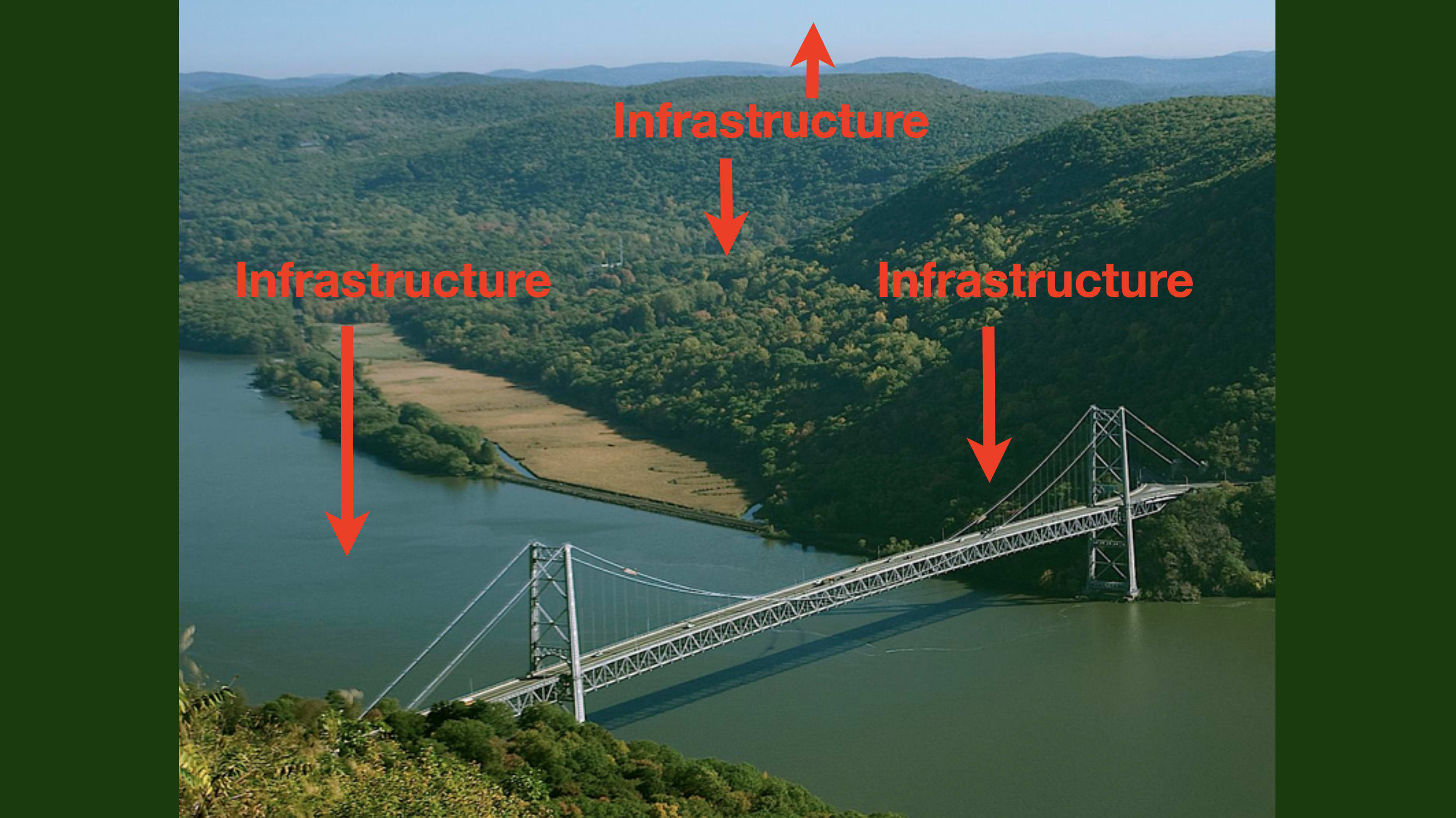

* A bridge is infrastructure. So is the river under it.

So is the local ecosystem—and Earth’s ecosystem.

So is climate. All of them need attention and work to maintain them properly.

Does anything change if we say “planetary civilization”? I think so, because it means we step up to the responsibility of adding the benefits of consciousness to Gaia as a whole.

Does that mean that Humanity and Nature are becoming one entity? Yes and no. Yes, because we understand the planet as one package of life.

No, because Humanity and Nature engage the future differently. Humanity operates with mental models and intention, and Nature doesn’t. The bridge was made as a result of intention; the river was not. Humanity can analyze Nature, but Nature doesn’t analyze Humanity.

* So. Our analysis shows that our intention to harness the energy of fossil fuels had extraordinary success—and an unwelcome effect on climate that standard Gaian forces won’t fix.

That’s okay. Now, our intentions are focused on fixing that problem. It will take a century or two, but I’m pretty sure we’ll succeed. One, because we can. Two, because the overwhelming cost of failing will become ever more apparent.

* Here is the reason to not be constantly panicking about how civilization might end: It takes our focus off the main event, which is how we manage civilization’s continuity and enhancement—working always from here and now rather than backward from some imaginary end state.

All that is needed is a shift of primary assumption—from “civilization might end at any moment” to “civilization will keep going for a long time.” We’re not at the end of civilization’s story. We’re in the middle of it, with 5,000 years to go at least.

Our job is to figure out what it means to act accordingly.

* One thing for sure, continuity requires careful attention to the maintenance of all the systems—including climate—that we depend on.

That’s the strongest argument for protecting Nature, because Nature is the most enormous and consequential self-maintaining thing we know.

A properly planetary civilization on Earth

has most of its durability built in.

* Thank you.