The Soul of Maintaining a New Machine

TTHEY ATE TOGETHER every chance they could. They had to. The enormous photocopiers they were responsible for maintaining were so complex, temperamental, and variable between models and upgrades that it was difficult to keep the machines functioning without frequent conversations with their peers about the ever-shifting nuances of repair and care. The core of their operational knowledge was social. That’s the subject of this chapter.

It was the mid-1980s. They were the technician teams charged with servicing the Xerox machines that suddenly were providing all of America’s offices with vast quantities of photocopies and frustration. The machines were so large, noisy, and busy that most offices kept them in a separate room.

An inquisitive anthropologist discovered that what the technicians did all day with those machines was grotesquely different from what Xerox corporation thought they did, and the divergence was hampering the company unnecessarily. The saga that followed his revelation is worth recounting in detail because of what it shows about the ingenuity of professional maintainers at work in a high-ambiguity environment, the harm caused by an institutionalized wrong theory of their work, and the invincible power of an institutionalized wrong theory to resist change.

The cover of Julian Orr’s influential Talking About Machines shows technicians working on the Xerox 5090 photocopier, introduced in 1990. Though they were doing messy blue-collar work, Xerox required the technicians to act and dress white-collar. They carried their tools in a briefcase.

The anthropologist was Julian Orr. In 1979, he was hired by Xerox PARC (Palo Alto Research Center) in northern California to provide technical support for two machines being developed there—the Alto computer and a color laser printer. By 1984 he had migrated to studying Xerox service technicians, encouraged by John Seely Brown, then a lab manager, later director of PARC. Orr’s research culminated in a remarkable book titled Talking About Machines: An Ethnography of a Modern Job, published in 1996. His book shows that the most baffling problems the technicians faced in their machines were solved by discussion, and the most instructive element in their conversation was what Orr calls “war stories”—narratives the technicians told each other about how they worked through a bewildering problem in a machine to arrive at a satisfying solution.

The stories also establish the teller’s contribution to the local community of technicians. Orr writes:

Given that the only status within the community is that of competent practitioner, fame can only be based on a reputation for extraordinarily competent practice, the ability to solve newer and harder problems. Since technicians normally work alone, achievements will only be known if the person responsible tells them. Moreover, technicians want the information to circulate, so that others can address similar problems. A team shares responsibility for its calls, so there is incentive to have all members competent for as many problems as possible.1Often, the issue was not with the copier but with unintentionally destructive behavior by the users. That, too, was considered fixable. Orr declares that the technicians’

practice is a continuous, highly skilled improvisation within a triangular relationship of technician, customer, and machine…. Narrative forms a primary element of this practice. The actual process of diagnosis involves the creation of a coherent account of the troubled state of the machine from available pieces of unintegrated information…. A coherent diagnostic narrative constitutes a technician’s mastery of the problematic situation.Narrative preserves such diagnoses as they are told to colleagues…. The circulation of stories among the community of technicians is the principal means by which the technicians stay informed of the developing subtleties of machine behavior in the field.2By the mid-1980s, Xerox copiers had reached such a degree of complexity that “individual machines,” Orr writes, “are quite idiosyncratic, new failure modes appear continuously, and rote procedure cannot address unknown problems.”3

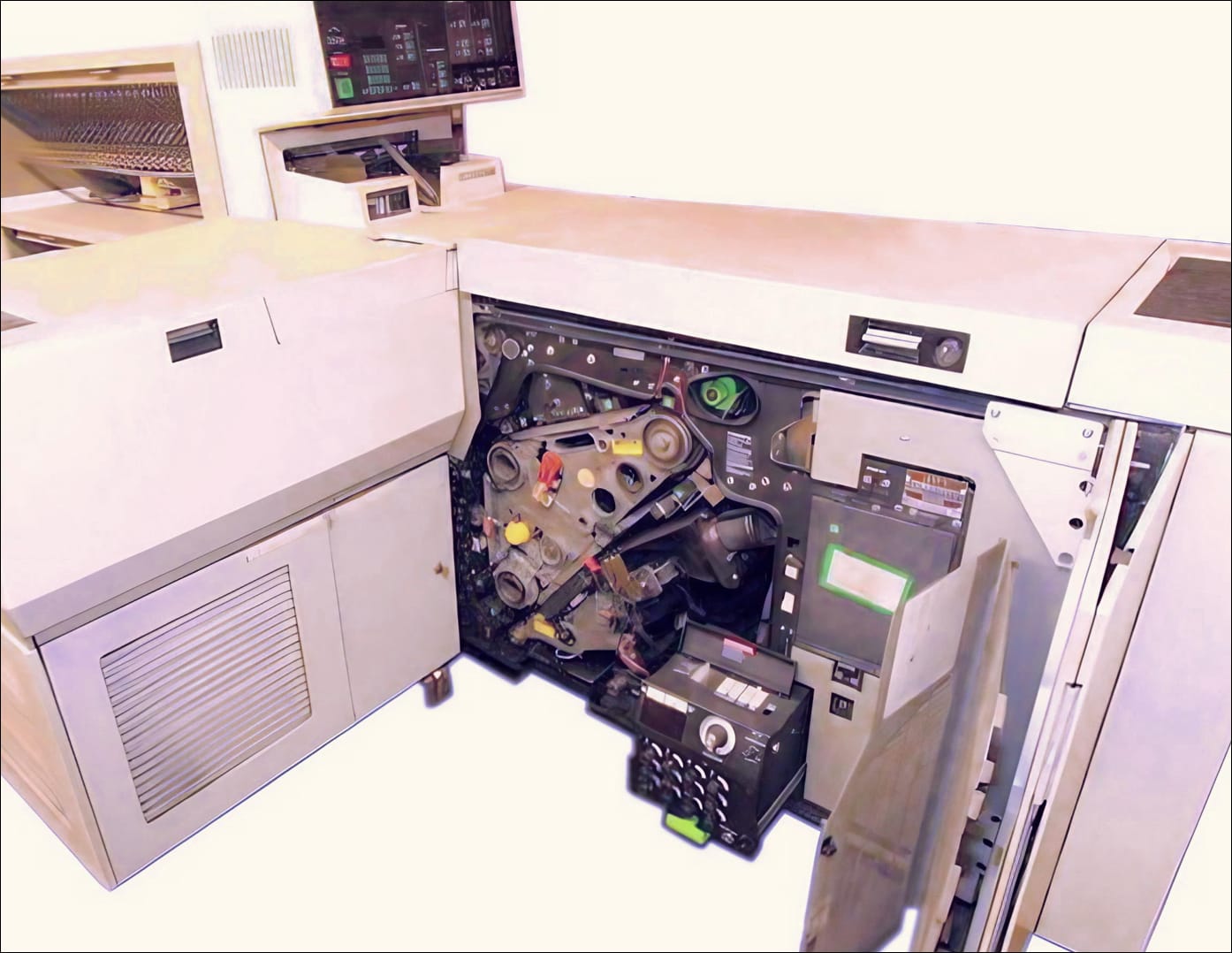

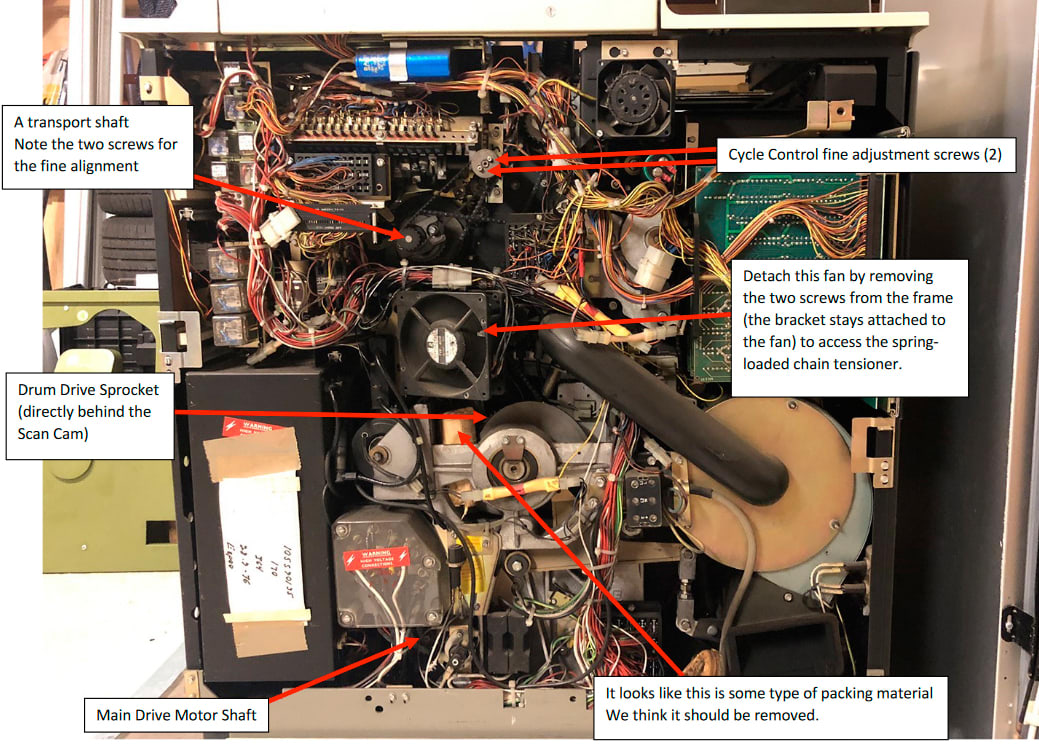

A Xerox 9400 with its panel open for technicians to get at the guts of the machine.

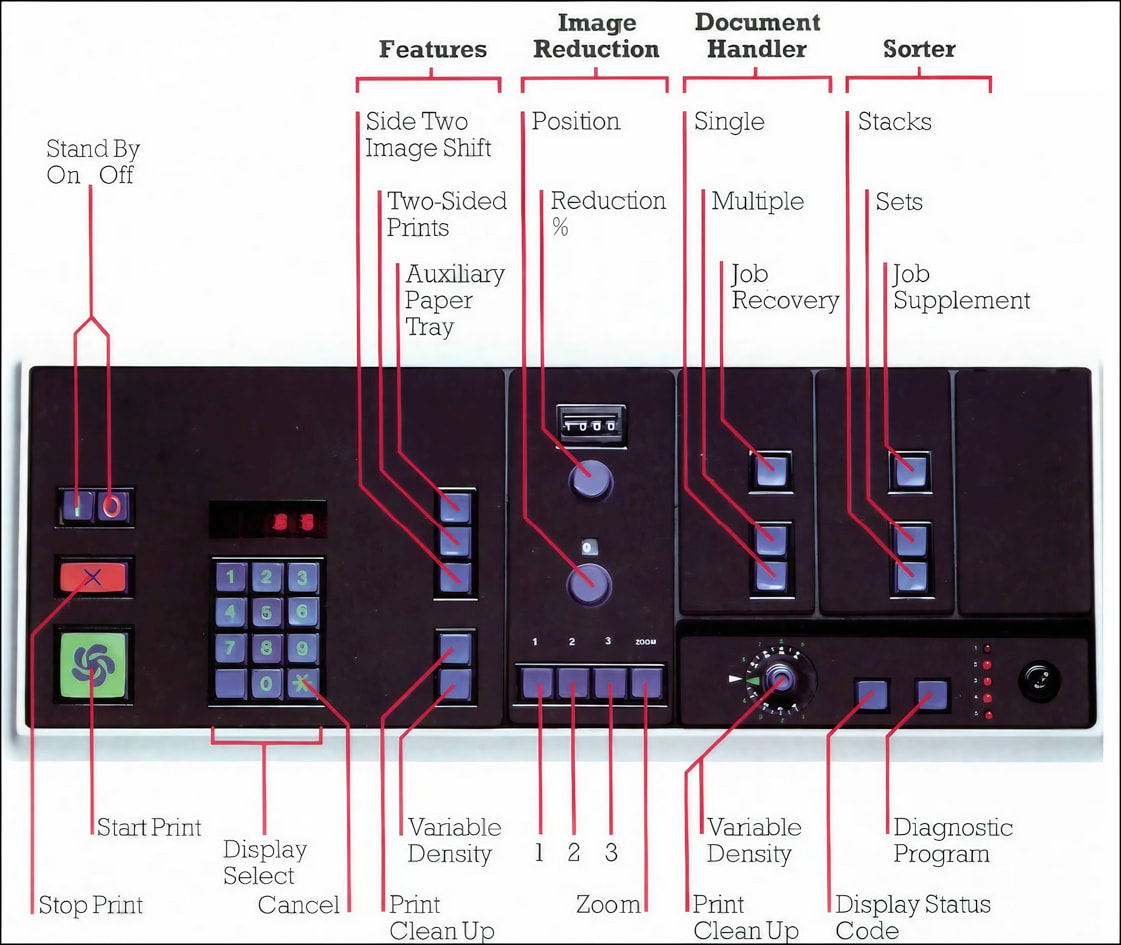

Specifying the exact features for a copying job on the 9400’s control panel was not for the faint of heart. Users varied in their sophistication. When the machine had a problem, some customers could communicate helpfully with the repair technicians. Many could not. Some were, in fact, the cause of the problem.

Jane Fonda’s first-day-on-the-job character is overwhelmed by a Xerox 9400 belching copies at her in the feminist comedy 9 to 5, made in 1980, co-starring Dolly Parton and Lily Tomlin. Her humiliating defeat by the copy machine was a common experience for office workers in those years.

For example, the famous Xerox 9400 that was introduced in 1977 weighed one and a half tons and took up floor space measuring nine by fifteen feet. It cost $85,000 ($430,000 in 2024). Automatically feeding up to 3,000 sheets of paper, it made copies at a rate of two per second and collated them into 50 separate bins. It could read and write two-sided sheets, and the image size was adjustable. Every stage of the process required extreme precision—from imaging to paper handling to managing the sequence of electric fields that transferred the image-bearing toner onto the paper, then pressing and baking the toner into the paper, and cleaning everything to be ready for the next image a half-second later. A fault anywhere in that sequence or in the control system could cause degraded copies or take down the whole machine.

A technician who serviced 9400s in the 1980s recalls:

This machine was the main method of information distribution for the entire Federal Government for quite a while… I took service calls on these machines coming from the Pentagon, the CIA, the State Department, the Defense Mapping Agency, the Nuclear Regulatory Agency, Pax River Naval Research Center, the National Institutes of Health, the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, and the National Bureau of Standards…. Xerox must have made an unbelievably enormous amount of money from that product—and spent an almost equally unbelievable amount maintaining them, because I also remember the nearly endless field retrofits we had to perform to keep them running…. Oh, those were the days!4The technicians were organized into regional teams, servicing all the machines within a geographic area. Each team member had sole responsibility for a group of customer offices and machines. Orr emphasizes that all their attention was focused on the work, with little to spare for the corporation that paid them. Indeed, they “shared few cultural values” with the rest of Xerox and did not seek to rise within it.5 They relished working within the technician-customer-machine triangle, where their competence was tested and rewarded daily.

Since half of the problems they had to fix were caused by misuse of the machines, they had an adage: “Don’t fix the machine, fix the customer.” The copiers were so sensitive that users could screw things up by using toner from a different machine or a cheap knock-off supplier. Or they could mistakenly put paper in the feeder tray curl-side-up instead of curl-side-down (it was vice-versa in other copiers).

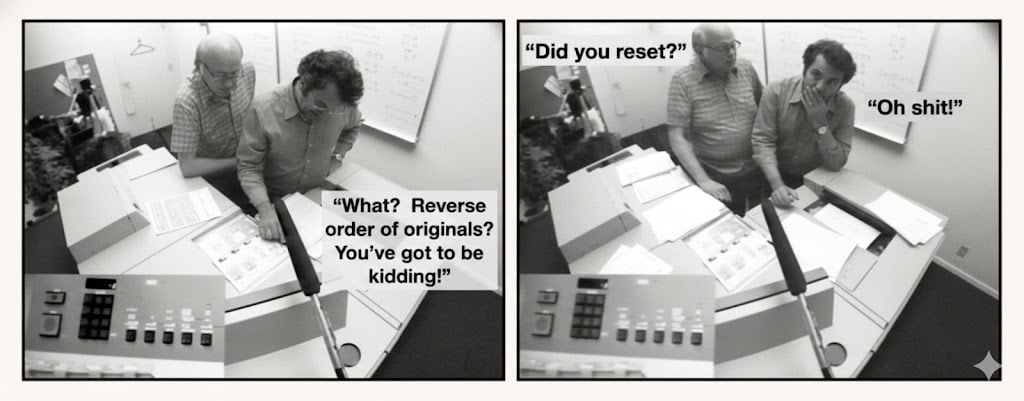

In 1983, PARC intern Lucy Suchman conducted a famously diabolical experiment with the supposedly user-friendly Xerox 8200 copier. She made videos of PARC people using it. Tech historian John Tinnell recounts what happened when PARC director John Seely Brown (who was a long-time motorcycle buddy of Xerox CEO Paul Allaire) took one of the videos to corporate headquarters: “[Brown] played the video for a room of Xerox managers. It featured two men struggling and failing to produce a copy of an article [Ronald] Kaplan had written. Everyone back at PARC knew [that] Kaplan was a world-renowned computational linguist, and [Allan] Newell was revered as a founding father of AI. The video showed Newell peering over Kaplan’s shoulder, oscillating between curiosity and confusion as the pair exhausted the full arsenal of their joint expertise, to no avail, for over an hour and a half. One of the Rochester men slammed his fist on the table and hollered, ‘Goddammit, Brown! What did you do, get those guys off the goddamn loading dock?’ Brown looked at him and smiled, ‘Well, actually, let me introduce these two stooges to you,’ He revealed Kaplan’s and Newell’s pedigrees, and the Xerox execs sat speechless.”9

Lucy Suchman later became the manager of the “Work Practice and Technology” research group at PARC, which was composed of all the anthropologists at PARC plus a few computer scientists. Julian Orr was a member from the beginning. Suchman’s 1987 book, Plans and Situated Actions: The Problem of Human-Machine Communication, became a classic text.

The machines were so complex that even sophisticated customers could lose their way—for example by failing to replace a baffle after clearing a paper jam (which would affect the paper’s temperature and cause further jams) or rashly re-using paper that had been through the machine once and was, therefore, oily (which would make rollers so oily that they could no longer feed properly).

Even when the problem was purely mechanical, the customer was a primary source of important diagnostic information about when and how the breakdown had occurred. That meant, says Orr, that “the customer must be initiated into the technicians’ community of discourse,”6 complete with an understanding of how the machine worked, how to recognize the noises it made at the various stages of copying, and the correct language to describe its many failure modes. Some customers resisted learning any such thing, and the technicians had to find a way to jolly them into learning it anyway. Orr writes that users were

taught by the technicians how to talk about the machine. They know what to observe—the state of the originals, where the machine leaves paper when it stops, and where in the cycle trouble occurs—and they know most of the terms to describe these phenomena.7As a consequence, the technicians became protective of the nuanced social relationship they built with each customer. Orr notes: “Technicians worry more about the social damage another technician can do in their territory than about what might happen with the machine, perhaps because the machine would be easier to repair than the delicate social equilibrium.8”

Ethnographer Orr had a sharp eye for detail. He noticed when a technician on a call began by examining copies that had been thrown in the trash and deduced from them that the problem with the machine was different from what the customer had reported. “The trashcan is a filter between good copies and bad,” one technician explained “Just go to the trashcan to find the bad copies and then… interpret what connects them all.”10

Another time, Orr observed a technician joking with a customer about the need to keep any engineers in the building away from a machine that needed fixing, because “engineers believe they have a right to fiddle with any machine they encounter, whether they know anything about it or not.”11 Orr recalls, “Engineers would go in and change adjustments, which offers limitless possibilities for disaster.”12

Orr noted that many of the technicians came from rural backgrounds, and nearly all—women as well as men—grew up as inveterate tinkerers. Half had studied technical subjects at junior colleges. A fifth learned their technical skills in the military, as had Orr. All received training at Xerox Document University in Leesburg, Virginia, and Orr did the same before undertaking his research on their behavior in the field.

In 1982, the Xerox 1075 inaugurated the 10 Series, which became known as “the most successful line of copiers in Xerox history and served to restore the company’s finances and morale.”16 The technicians Orr studied were primarily responsible for servicing this machine.

The machine he studied for three weeks in Virginia was the then-new Xerox 1075, introduced in 1982 with a $55,000 price tag ($180,000 in 2024 dollars). It was a medium-sized copier that could churn out 70 copies a minute and featured an advanced level of electronics that performed onboard diagnostics and kept error and use logs. Orr writes, “Designed for a monthly volume of less than 40,000 copies, it was placed in situations demanding six and seven times that, which quickly produced unanticipated problems.”13

The notorious 1970s Xerox 4000 copier. On the “Xerox Nostalgia” website, technicians remember it as “a dog in terms of reliability,” “a beast,” “an electromechanical monster, and dirty,” “a nightmare to keep it working,” “I hated this product!” “I still suffer from two 4000-induced medical conditions: ‘4000 knees’ and ‘A-transport replacement lower back pain’!” and “I got quite proficient on the 4000/4500 and was once told by a Leesburg trainer that an experienced 4000 rep could fix anything.” This photo of the back of the 4000 was taken by a hobbyist who set about restoring the machine in 2019, showing some of the tips he got from battle-scarred technicians on how to get it going. With their help, he succeeded.

Orr notes that the technicians he studied were accustomed to dealing with unanticipated problems because of their years of experience with Xerox’s worst copier, the infamous 4000, first released in 1970 and kept in use far past its expected lifespan. “Consequently,” Orr writes, “successful 4000 technicians developed considerable resourcefulness and a propensity for pooling their information with their fellows.”14

Thanks to his training, Orr could blend in with the technicians as a colleague and decipher the cryptic technical language of their war stories, which were always told with extreme brevity. “This brevity,” he explains, “is a matter of cultural propriety and competent practice; it would be inappropriate to waste everyone’s time with the superfluous.”15 Specialists talking to fellow specialists speak in dense jargon, not to exclude outsiders but to honor their listeners’ expertise and engage it. “Story-telling is an interactive practice,” Orr adds. “You tell the story concisely, but if you notice one of your listeners looking confused, you back up and provide as much detail as necessary so they understand.”17

The war stories were never about routine maintenance or standard problems that everyone knew how to fix. Instead, Orr says,

Technicians like new manifestations of the extremes of machine behavior or of human behavior with machines. Problems that require consideration of the chains of cause and effect in the machines and that shed new light on those chains are interesting to talk about…. The stranger the sequence of events and interactions producing the machine behavior, the better the story is, and the more fun it is to tell.18Orr recites the exact wording of one war story told by a senior technician to his peers. (The language is characteristically dense and technical; I’ll explain in a moment what the technician’s peers heard and understood in the story.) The man said:

When you have a shorted dicorotron, you can’t even get the machine to run—it’ll cycle about twice and then shut down and give you an E053. First time with the new boards—the new XER board configuration—it wouldn't cook the board if you had an arcing dicorotron. Instead, now it trips the 24-Volt Interlock in the Low Voltage Power Supply, the machine will crash, and when it comes back up, it'll give you an E053. It may or may not give you an F066 that tells you the short is in—you know, check the xerographics. That's exactly what I had down here, at the end of the hall, and Weber and I ran for four hours trying to chase that thing. All it was was a bad dicorotron. We finally got it, ... run it long enough so that we got an E053 with an F066, and the minute we checked the dicorotrons, we had one that was totally dead. Put a new dicorotron in it, and it ran fine. Yeah, that was a fun one.19His peers understood that this story concerned an upgrade to the 1075 copier that, in the process of solving one problem, created a more difficult new one, which combined a meaningless error code with a maddeningly intermittent correct error code. The upgrade was an improved “XER” circuit board that no longer burned out when there was a short in one of the four “dicorotrons” that managed the electrical fields that did the copying (“the xerographics”). Instead, the machine now shut down and displayed a misleading error code—“E053”—indicating a blown circuit breaker, which could be caused by any number of things. The documentation for that error code advised that the problem would go away if certain specific components were replaced—but it never mentioned dicorotrons. Technicians would spend hours replacing components, and the machine just kept on crashing. It turned out that if you ran the process to failure enough times, every now and then, a seemingly spurious “F066” error code would show up, and the documentation for that error code led straight to the dicorotrons.

For anyone to solve that problem in the future, they had to know and remember the whole sequence. That was the point of telling a rousing war story about it. (I prefer to call them detective stories. They are all about teasing out the crucial clues from a confusing excess of potentially relevant information.) Other PARC researchers later wrote that the technicians have a

strong preference for building up a story of what might be wrong with a particular machine by gleaning information from many sources, including other people in their work group, artifacts (e.g. the machine itself), and formal and informal documents.20Clever word, “gleaning.” It means “to frugally accumulate resources from low-yield contexts.” You peruse a mess of ambiguous data points and get some of them to disambiguate each other.

Orr notes that tracking down the cause of a problem is often best done jointly with another technician:

In most of the hard diagnoses observed, solution was discovered through re-interpretation of known facts and following the new interpretation with new investigations. This is one of the reasons that consultations and joint trouble-shooting are so popular and effective. The presence of another guarantees another perspective and makes it easier to experiment with new interpretations. It also provides someone to whom to tell stories, who will tell stories in return…. The consideration of the present with reference to known diagnoses of the past, is an essential part of diagnosis.21Orr has a withering critique of the diagnostic “Fault Isolation Procedures” in the documentation—the service manuals—issued to the technicians:

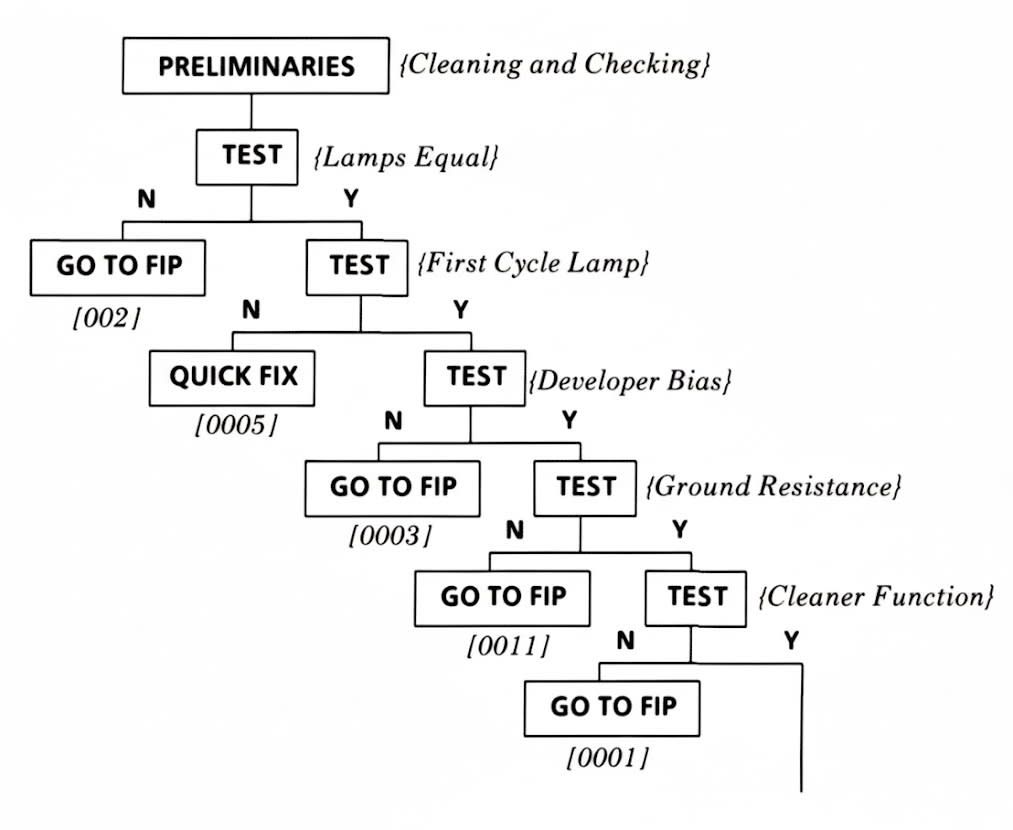

This directive documentation is designed not to provide information for thinking about the machine and its problems but to direct the technician to the solution through a minimal decision tree…. A system that fixes the machine without either customer or technician knowing how or why is unlikely to be acceptable. Consequently, when the technicians use the directive documentation, they try to determine the purpose of the various tests, to understand what the documentation is testing, to know what they are doing.22

A typical diagnostic decision tree in the service manual for the Xerox 1075 copier. It is a “Fault Isolation Procedure” (FIP) to correct “High Background/High Density” in copies. The tests mostly lead to other FIPs on other pages of the manual. They are entirely directive—do this, then do that. They do not invite understanding or suggest clues to look for outside the decision tree. They contain nothing learned by technicians in the field. They can offer nothing about problems that emerged after the manual was written.

“The documentation,” Orr writes, “is designed not to enable deduction.”23 Sometimes the manual would suggest something insane, such as solving a particular problem by replacing—at vast expense—all the circuit boards in the entire machine. No one would ever do that. John Seely Brown, the Director of PARC from 1990 to 2000, recalls:

Xerox had these beautifully produced instruction manuals for the technicians. They were big. There was a sort of social prestige in leaving them behind on a call. I mean: A, they were useless; and B, you looked like a fool walking in to fix a copier carrying a big encyclopedia.24The field technicians had no part in writing the manuals. They were written by the engineers who had designed the machine and by management, who, Orr says, “[seek] control over their employees, through control of the knowledge necessary to do the job, and can hire cheaper employees, since they do not need skilled labor.”25

At one point, Orr states explicitly what his entire book proves: “Repair and maintenance are not in any sense unskilled work.”26 He observed that the technicians operated with far more extensive knowledge than the documentation could provide. (An important exception was the schematics. Because the schematic diagrams showed how the machine’s electrical, electronic, mechanical, and pneumatic systems were connected, the technicians considered them accurate and helpful for tracing possible sequences of cause and effect in a machine’s misbehavior.)

The technicians were dismayed when—sometimes encouraged by the documentation, as in the dicorotron war story—they had to resort to “shotgunning,” which meant just swapping new parts into the machine until a problem went away. Evaporating a problem rather than solving it meant that nothing was learned that might be helpful next time. The cause remained a mystery, and so did the remedy, along with any hint of how to prevent the problem from recurring. Orr emphasizes the effort the technicians made to earn and maintain the customer’s confidence:

The point of telling the customer what has happened is to establish that the problem was addressed in a professional manner, and this requires being able to tell what the machine is doing and being able to say what was done to fix it.27Nevertheless, shotgunning was preferable to failing to fix the customer’s machine. That was unacceptable. Service techs felt obliged to live up to what Orr calls their “gun-slinger mystique” of “the lone technician walking into the customer site to cope with whatever troubles lie therein.”28

To be effective, Orr concludes, the technicians had to “become connoisseurs of the variations in machine misbehavior and of new shades of misunderstanding displayed and practiced by customers.”29 The enemy of all technicians is chaos, he says. The service techs he studied insisted on carefully tuned reliability in the machines they serviced and valued tidiness at the worksite—no mess of tools, parts, and toner stains all over the place. This was, Orr says, core to “their identity as technicians—defined as those who fix the world and make it right.”30

That might do as a description of maintainers in general: Those who fix the world and make it right.

Orr’s study quickly became famous and infamous throughout Xerox. A few, mostly Orr’s colleagues at PARC in California, thought it showed a revolutionary path to the future for the company. The many, especially at Xerox headquarters back east in Rochester, New York, thought the study revealed how much time—and company money!—the technicians were wasting just chatting with each other instead of doing what they were paid to do: working with customers. Since customer service was treated primarily as a cost center, some managers suggested the company could save serious money by cutting back on the socializing by the technicians.

In April 2000, the Harvard Business Review published a piece by PARC researchers John Seely Brown and Paul Duguid titled “Balancing Act: How to Capture Knowledge Without Killing It.” Referring to the technicians as “reps” (short for “customer service representatives”), the paper summarizes Orr’s research this way:

Orr… studied what reps actually did, not what they were assumed to do…. They succeed primarily by departing from formal processes…. Orr found that a quick breakfast can be worth hours of training. While eating, playing cribbage, and gossiping, the reps talked work, and talked it continually. They posed questions, raised problems, offered solutions, constructed answers, laughed at mistakes, and discussed changes in their work, the machines, and customer relations.Orr showed that the reps use one another as their most critical resources. In the course of socializing, the reps develop a collective pool of practical knowledge that any one of them can draw upon. That pool transcends any individual member’s knowledge, and it certainly transcends the corporation’s documentation. Each rep contributes to the pool, drawing from his or her own particular strengths, which the others recognize and rely on. Collectively, the local groups constitute a community of practice.31Some researchers at PARC noted that many of the technician team’s important insights could be applied throughout Xerox globally but were confined within that team. Since engineers at PARC specialized in computer networks—Ethernet was invented there—Orr’s colleagues imagined a company-wide system linking all of Xerox’s 25,000 technicians via the Internet in a global “network of practice” where, to the edification of all, they could share their best solutions and workarounds. The idea was named the Eureka project.

It began with a failure. The culmination of a multi-year PARC project to develop a state-of-the-art, artificial-intelligence-driven expert system to help the technicians diagnose problems was finally shown in 1991 to some technicians for comment. They said the system was ingenious, but it wouldn’t be much use because it covered nothing but common faults that everyone already knew how to detect and correct. Confronted by Orr’s observations, the project’s developers realized they had to focus on

the importance of non-canonical knowledge generated and shared within the service community. It suggested to us that we could stand the artificial intelligence approach on its head, so to speak; the work community itself could become the expert system, and ideas could flow up from the people engaged in work on the organization’s frontlines.32They resolved to replace the expert system with “a system for experts.” The hard-won knowledge that each technician team developed would instantly be available to all the other teams. “The project,” Brown writes, “set out to create a database to preserve resourceful ideas over time and deliver them over space.”33

In 1991, a Xerox district manager in Colorado got wind of Orr’s research and invited him to a meeting in Denver to help develop an idea. Orr recalls:

The most significant moment of the meeting occurred when the District Service Manager told a story. He had recently had his furnace repaired. The technician doing the repair had been carrying a portable radio, with which he maintained a continuous conversation with his colleagues, other technicians repairing other furnaces elsewhere. This use of the radio for constant communications struck the manager as something which technicians in his organization could use.34The participants in the meeting noted that Xerox service technicians are “one of the lowest levels of the corporate hierarchy,” and yet they “have more contact with the corporation's customers than any other member of the corporation and so should be valued.”35 They further noted that customers’ machines were spread so widely all over Colorado that many technicians spent most of their time driving alone, unable to meet very often with other technicians.

The first order of business, they decided, was to involve technicians directly in building the scheme, or the whole thing would look like just another unwelcome intervention by management in their work lives. Ethnography to the rescue. Conspicuously non-management Julian Orr was funded to study four teams for three weeks to find out if they wanted portable radios and to pique their interest in helping design the project. The technicians told Orr they would love to have two-way radios that could be used like portable telephones to communicate with their families, co-workers, and customers—but not with their managers, thank you.

Accordingly, radios were distributed to five work groups. Orr was invited to study the radio system in use for six months and to work with the technicians on improving the system. (Cell phones were not considered because they couldn’t be group-oriented the way logic-trunked radios could.) The technicians insisted that their communications must be “free from interference or even monitoring,” and the district manager supported them in this. Orr recalls, “On many occasions during the fieldwork, [I] found it necessary to assure other technicians that managers were not allowed to use the radios.”36 Orr praises the Colorado district for honoring the privacy of the technician teams:

This relinquishment underscores a dilemma of modern managers: If they are not controlling, what then is their function? Given these pressures, the managerial decision to let the information remain available only to the technicians is a remarkable event and an achievement for those involved.37The radio project was a roaring success. Orr observes that the technicians “mostly work alone in other people's offices and rarely spoke to any colleagues; now they spend part of their time on the air supporting each other and often converse while driving home at the end of the day, unwinding and getting the day's events in perspective.” Also they “find it easier to share parts or to coordinate trips to the warehouse when necessary. They exchange information about weather or traffic.” When Orr asked them if a message system wouldn’t work just as well, he was told “that the stress in someone's voice cannot be conveyed in a typed message.” “The workgroups have become real through this tool,” they said. “The groups now are based on real and continuing relationships which could not be achieved with weekly meetings.”38

Outside of the enlightened Colorado district, however, perspective on the radio-empowered technicians shifted. Orr writes:

After six months of experience, the technicians were quite clear that the radios helped them with diagnosis, with coordination, with morale, with parts supply problems, and with the training of new technicians, but these were not acceptable benefits from the corporation's perspective, which required demonstrable dollar savings.39Xerox corporate decided that since radios made the service reps more efficient, the company could save money by employing fewer reps. To lower the cost of the radios, Xerox reduced their power and range and thus their ability to connect all of the technicians in the district. “The original desire to help the technicians enhance their own practice,” Orr writes, “disappeared from managerial discourse.”40 For Xerox corporate, the issue was simple. The whole point of any improvement in customer service was to reduce its cost, period.

Nevertheless, within a few years, all 25,000 Xerox service reps worldwide were furnished with portable radios to enrich the peer-to-peer discourse that made their work go better.

The radio breakthrough in Colorado was a relatively quick win. Getting the Eureka project from vision to reality, it became clear, would require a much longer slog because the concept violated Xerox’s deeply embedded views of how to run a company—from the top down. The lowly technicians should be guided solely by their superiors, not by each other.

(I can tell this story in some detail thanks to the profusion of papers published about Xerox service practice and Eureka between 1986 and 2011. Julian Orr wrote 11 of them, including his book and the 1990 PhD thesis it was expanded from. Other authors I’ve relied on are John Seely Brown & Paul Duguid, Daniel Bobrow & Jack Whalen, plus Olivier Raiman, David Bell, Mark Shirley, Cindy Gordon, Robert Cheslow, Norman Crowfoot, Steve Barth, Yutaka Yamauchi, and Andrew Cox.)

Eureka’s primary designer and champion at PARC was a French national named Olivier Raiman. One of his colleagues, Cindy Gordon, later wrote of him: “Olivier Raiman was visionary, and his passion, energy, and commitment helped create momentum for the Eureka project.”41 Establishing some kind of momentum was surely needed, because the managers in Worldwide Customer Services who had oversight of the technicians saw no value in the project and took every opportunity to block it.

Their view was partly the product of an earlier effort to “de-skill” the technicians. After the Vietnam War ended in 1975, the supply of technicians trained by the military dried up. “Xerox decided,” writes one of the PARC researchers, “to use less skilled, less experienced service people. It moved away from the documentation and training that described the principles of product operation…, and moved toward ‘directive’ repair and adjustment procedures.”42 These were the simplistic Fault Isolation Procedures that the technicians struggled to penetrate, trying to discern their purpose. The procedures were all “how” and no “why.” The idea of hiring less skilled technicians quickly died, but the documentation-for-dummies remained unchanged.

The managers were so adamant that the directive procedures were sufficient that the technicians had to pretend that was so in order to keep their jobs. The formula was: “Quality service meant uniform service, and uniform service meant following the instructions in the manual.”43 One service rep told a PARC researcher that he never made private annotations in the manual because that might suggest he was giving nonstandard service. Then, the researcher reports,

he showed his "cheat sheet" with recent tips for difficult service problems that he used as an augmentation to the manual. In essence, he was keeping two sets of books: one to show quality inspectors, and one to use for a quality job!44What would have happened if the technicians dutifully never ventured outside the manual? The opinion at PARC was:

If the technicians had abandoned diagnosis when the directive documentation did and followed the catch-all rule, which was to replace the machine, they would have drained Xerox of customers.45 Fortunately for the company, the technicians were more loyal to their customers than to their managers. They would quietly defy Xerox policy to fulfill their professional imperative to fix their customers’ Xerox machines, no matter what. In Julian Orr’s view, “The corporate use of information for leverage and control contrasts with the technicians' attitude of sharing it among those who can use it.”46 While the managers wanted to suppress improvisation, the technicians celebrated it—and had to keep it secret. Orr adds in disgust:

During the 1990s,… the corporation created mandatory structures of meta-work, work about belonging to the organization, which both kept the technicians away from their work with machines and customers and was used to judge them for their performance reviews.47The result, writes Orr, was that the technicians “do less work now servicing customers and more servicing Xerox.”48

Consequently, while the technicians were intrigued by the idea of Eureka sharing their knowledge globally, they had reason to doubt it would go anywhere. One old-timer among the technicians remembered how

decades ago when he started at Xerox, he submitted a suggestion on how to install a machine more efficiently. For six months he did not receive any feedback about the suggestion. Then he saw a published bulletin with his idea, attributed to the person who received the suggestion over the phone. After that, the service engineer did not submit any ideas.49Furthermore, Orr was told, other technicians might pay no attention to Eureka because it would look like just another lame offering from on high. In their experience,

Information which is distributed to the technicians… is often so fragmentary that the technicians do not perceive it to be of any use at all, and information from the corporation is usually regarded as suspect until confirmed through community experience.50Eureka’s lead champion, Olivier Raiman, describes the resistance this way:

Eureka was about a commitment to constant listening and adaptation…. In fact, it required an acceptance of what many companies consider a radical concept—the person who does the job is in the best position to know how it can and should be done. This is a scary proposition for middle managers because it fundamentally changes their job description and takes away their role as the residential expert on operational functions.51Orr concluded that the asymmetry between the managers and the technicians was stark: “Management has most of the money and power.”52 The heavyweights at Worldwide Customer Service said to the PARC researchers, essentially, “The service representatives work for us, not you. The system we have is working just fine. You are not welcome to screw it up with one of your harebrained academic theories.”

The emphatic “No” to Eureka from headquarters made Olivier Raiman search for a fragment of the company that might say “Maybe.” He found one in his native France. With permission to immerse himself in the work-life of French service technicians, he set about designing Eureka around their needs. Xerox corporate refused to provide any money for the work, so PARC and Xerox France funded it. Eureka’s designers remember:

In the initial stages, we sometimes had to operate like a guerrilla group because opposition was enough to kill the project…. We conducted our first experiment in France partly because it was out of sight of the central Xerox organization.53In 1994, France had the world’s first national computerized communication system--French Minitel, with five million terminals in use. It would provide the infrastructure for the technicians to connect with the Eureka database.

In their Harvard Business Review paper, Brown and Duguid summarized how the database of tips was assembled:

Reps, not the organization, supply the tips. But reps also vet the tips. A rep submits a suggestion first to a local expert on the topic. Together, they refine the tip. It’s then submitted to a centralized review process, organized according to business units. Here reps and engineers again vet the tips, accepting some, rejecting others, eliminating duplicates, and calling in experts on the particular product line to resolve doubts and disputes. If a tip survives this process, it becomes available to reps… who have access to the tips database…. So reps using the system know that the tips… are relevant, reliable, and probably not redundant.[Xerox France] offered to pay for the tips, but the pilot group of reps who helped design the system thought that would be a mistake, worrying… that payment for submissions would lead people to focus on quantity rather than quality in making submissions. Instead, the reps chose to have their names attached to tips. Those who submit good tips earn positive recognition. Because even good tips vary in quality, reps, like scientists, build social capital through the quality of their input.54The process relied in particular on the most experienced technician specialists known as “tigers.” France’s leading tiger, Eric Delanchy, joined Raiman in championing the idea with technicians nationwide. Because the tigers were “consultants to other technicians with a mandate to teach and share expertise,”55 they were best equipped to frame the tips in the most helpful way. The researchers from PARC remember: “We worked interactively with the tigers in France to improve the software, often responding overnight; this transformed [Eureka] from our idea to their tool.”56

Each tip had a three-part structure: Problem, Cause, Solution. That made the tips easy to scan quickly. Here’s an example:

Problem: When running Xerox coated stock from Tray 3, customer gets jammed PO8- 19X, and message on copier indicated: ”Paper width is too narrow.”Cause: Xerox coated stock in Tray 3 is too flat or loaded with the curl the wrong way, causing the sheet to be fed skewed. The sheet is still skewed at the registration sensor. Solution: Contrary to what we have been taught, with this stock, load curl down in Tray 3. Instruct customer how to check for curl in paper and flatness. Totally flat stock seems to jam right away. Last resort is to coat the registration transport with antistatic fluid. The fluid will hold up for approximately 10,000 to 15,000 copies. Any question, feel free to contact Employee #930124 — Michael Posus, CST Twin Cities District57 Eureka was still in rudimentary form in France when the designers first tested it for efficacy. They picked 40 technicians to be trained on Eureka and matched them with 40 similar but Eureka-less technicians to act as the control group. Their work was measured with the standard Xerox metrics, including:

cost of parts, service time, number of unscheduled maintenance calls, interrupted calls, and callbacks…. The metrics after two months were startling. The experimental group had an approximately 10% lower parts cost and 10% lower average service time than did the control group, without differing significantly in the other service metrics.58 That convinced the leaders of Xerox France. They rolled out the system to all 1,300 technicians in the country. Within a year, new validated tips were being added at a rate of one a day, coming from 20 percent of the technicians. On average, the technicians were consulting the system more than twice a week. “Xerox France, compared to the rest of Europe,” the PARC researchers report, “went from being an average or below average performer in service to being a benchmark performer. The French service metrics were soon better than the European average by 5-20%, depending on the product.”59

Back in the US, Xerox corporate was still not persuaded, but a senior manager in Canada named Mark Hill was. In 1996, he invited the Eureka team to build a Canadian version. Once again, a leading tiger was essential to championing the project. There was no Minitel platform to work with, but the tiger, Michel Boucher, said some service technicians were already using a networked bulletin board system accessed via laptop and modem. Why not convert Eureka to work on the bulletin board? The database of tips would now be conveniently searchable thanks to new software developed at Xerox called SearchLite.

Boucher trained all the other tigers on how to use the system so they could then train the rest of Canada’s 1,200 technicians. They had to do it all in their spare time because, as the PARC developers recall, “Xerox expected technicians to author tips and validators to provide rapid turnaround and validation of submitted tips without any relief from their current workloads.”60 Along with expecting the work to be done for free, management required that it be done to schedule. The PARC researchers explain how well that worked:

Management had never dealt with a program in which the requirements emerged from experiments with pilot users, iterated until the users felt the program warranted large-scale deployment. Managers would try to set deadlines for us to get things done, independent of our process for rapid prototyping and debugging with extensive community involvement. The clash of these two different design and deployment methods had negative results. Some higher-level managers lost some faith in the ability of the Eureka team to deliver.61But they did deliver. After six months of intense work, Eureka launched in Canada in early 1997 with support for 20 Xerox products. Soon, there were 1,900 validated tips for 76 products, and the cost savings for product maintenance were 5 to 8 percent, the same as in France. Cindy Gordon, who was responsible for overseeing the project, writes: “Eureka is a great example of what might be called vernacular knowledge sharing — that is harvesting, organizing and passing around insights that come from the grassroots of an organization.”62 She notes that the Canadian experiment was so successful, “Some technicians in Minneapolis actually stole the software and access to Eureka and started using it on their own.”63

At last, Xerox’s Worldwide Customer Service was compelled to pay attention, although, as one of their officers, Tom Ruddy, recalls,

What it really took was testimonial video clips of old-school, hard-nosed, 25-years-of-experience service technicians telling their personal stories of how Eureka made a difference to them.64The project developers quickly learned that expanding to all 10,000 technicians in the US would meet new hindrances from the “much more bureaucratic and hierarchical” organization in America. They observed that

we were constantly trying to balance our belief that simpler was better with corporate managers’ beliefs that if Eureka was the answer, they wanted to be the one to generate the question.65One manager, for instance, insisted that accessing the whole project through Microsoft’s web browser, Internet Explorer, would simplify everything. In fact it complicated everything, just as the developers had predicted. Cascading versions of the browser, operating systems, and other software often failed to work together and had to be constantly updated on 10,000 laptops, which delayed the project for months.

Worse was management’s failure to understand that Eureka only spread successfully through direct contact among technicians, as proven in Canada and France. The developers recall:

We had originally suggested to… management an alternative ‘‘participatory deployment’’ strategy in which the pilot champions, technicians, and managers most knowledgeable about Eureka would go to other locations in the US service community and talk about their experiences and ideas. Because these people were peers, the technicians would trust them. During a relatively short time, Eureka would have spread across the entire country.66Instead, Xerox employed its customary “spray and pray” distribution mode. For the June 1998 launch, the company

distributed Eureka CD-ROMs to the field managers, who were then expected to distribute them to technicians in their work groups. The CD included a computer-based training module; no hands-on training or direct engagement with technicians around the program was planned.67Use of the system spread very slowly.

Yet spread it did. The technicians who loved it gradually infected their peers with comments like “In all my years in Xerox, the two best things ever given to us are the radios and Eureka.’’68 The original plan was to install the system throughout the US before going overseas, but, as the system developers later reported, “demand from technicians in Europe, Latin America, and Asia was so intense that the corporation had to begin distributing Eureka worldwide.”69 Soon, it reached all 25,000 service reps in the whole company.

Eureka was run by PARC, deploying its extensive computer and connectivity resources. When researchers examined how the scaled-up system was being used, they found some surprises. They had assumed that Eureka would be consulted mainly as a last resort, when all routine solutions to a problem had been exhausted. Instead, they discovered that many technicians “use it as a tool of first rather than last resort.”70 One user reported:

I check Eureka before I go to a site, that way when I get there I already know what parts to bring in. The customer is always impressed when you show up and already have an idea on how to fix the machine, and have the part with you. They just love it.71Another said: “Eureka is almost like having another technician with you because you can bounce your ideas or your thought processes off the Eureka database.”72 Another said he studied Eureka’s problems and solutions because “attending to how others found workarounds has helped him develop his own skills.”73

Best of all, Eureka gave the technicians a way to build their reputation for competence and generosity within the global fellowship of their peers—and with the company at large. In their Harvard Business Review paper, Brown and Duguid report, “At a meeting of Xerox reps in Canada, one individual was surprised by a spontaneous standing ovation from coworkers expressing their respect for his tips.”74

The whole of Xerox received accolades. At the time, many corporations were trying to build sophisticated “Knowledge Management Systems,” and Eureka was a rare success story. In 2002, Cindy Gordon reported that

funding for Eureka has steadily increased in the range of 60 percent year over year.…Return on investment has been in the range of tenfold, but, most important, management has supported Eureka at all levels in the organization.75Xerox announced that Eureka was transforming the company and henceforth, “Knowledge Management is our culture.” The company’s Worldwide Customer Service division, which had fought Olivier Raiman for so long, honored him with a plaque praising him for building Eureka “despite resistance from us.”76

It appeared that Julian Orr’s study really had revealed a revolutionary path to the future for Xerox, just as his colleagues at PARC had hoped and lobbied for a decade earlier. Or had it? How deep did the revolution go? As Cindy Gordon noted in 2002, “The Eureka project also had pockets of resistance, and some remain. Some of the biggest opposition came from company strategists.”77

The company’s 25,000 technicians—comprising a fourth of Xerox’s entire workforce—had their titles elevated to “customer service engineer,” but they were still not paid for the time they spent on generating tips, validating them, and constantly pruning and updating the Eureka database. The system’s developers also noted that the technicians and their lore remained oddly isolated from the rest of the company. They wrote, “No formal process incorporates Eureka’s information back into the documentation.”78 And:

One type of tip content was suggestions for better ways of doing things, including proposing modifications to the machines. Technicians are in a good position to notice when a machine was being overused for its purpose, and to suggest to a sales person that the customer might be ready for an upgrade. Viewing field service as the frontline to your customers dramatically changes the perspective on their role, and could engender new strategies for the service force.79To my eye, Xerox never got past viewing customer service as a cost center. The dense lore in the Eureka database proved that the company was ignoring a priceless value center. The service technicians were Xerox’s primary interface with its customers. The techs knew everything about the customers’ real use behavior. They knew exactly what made the machines fail and what made customers unhappy—crucial data for any company. They really were engineers: They solved emergent problems in the machines with a high degree of creativity. More thoroughly than the most adept salesperson, they routinely figured out how to shape their customers’ experience toward satisfaction.

(“In their frenzy to earn their bonuses,” Orr recalls, “Xerox salespeople would tell the customer that the machine would do whatever the customer wanted. The technician could later explain what it would really do.”)80

If Xerox had deeply reoriented itself toward service, the best technicians—the tigers—might have been considered for promotion paths into sales, design engineering, and manufacturing. Xerox’s salespeople could have been required to go on occasional repair calls to learn the perspective of the actual users of the machines, not just the account managers they sold to. Ditto the company’s design engineers: Let them watch their brilliant machines fail in mysterious ways. Let them study the myriad paths to destructive misuse by the customers and figure out ways to design around them. The company’s mid-level high-fliers slated for senior management could, in preparation for promotion, get trained up on a current machine at Xerox Document University and then go on some service calls for that machine, ideally in the company of a savvy tiger. Take that knowledge to the top of the corporation.

None of that happened, of course. Xerox declined after 2000, and the company’s glory years and Xerox PARC faded into history.

A byproduct of the Eureka success story was popularization of the term “community of practice.” The concept was developed at the PARC-adjacent Institute for Research on Learning in Palo Alto and published as the core idea of a 1991 book on apprenticeship titled Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation, by Jean Lave and Etienne Wenger. Their investigation of apprenticeships among butchers, navy quartermasters, tailors in Liberia, and midwives in Yucután showed that potential recruits to a practice were allowed to hover at the edge of the work, observing. Then they were given simple, routine tasks, and if they showed promise, gradually they were granted more complex tasks. It was not a course of study; it was the stepwise joining of a work community, with all of its skills, values, lingo, jokes, friendships, and tricks of the trade. “The community,” Wenger notes, “is the living curriculum for the apprentice.”81

Brown and Duguid draw an important distinction between the communities of practice embodied in the technician teams and the “network of practice” that Eureka became:

People in such networks have practice and knowledge in common, [but they] don’t interact with one another directly to any significant degree…. It produces very loosely coupled systems.”82One thing lost in Eureka was most of the wisdom that the service teams developed about dealing with customer issues, perhaps because, while all 25,000 technicians had the same machines in common, each local team had unique customers.

As years went by and social media like Facebook, Reddit, and YouTube proliferated online, all manner of virtual communities of practice emerged that did encourage interaction. You may recall my informant on Twitter who told me about rebuilding his 1996 Toyota guided by Timmy the Toolman YouTube videos and about the “robust community of people that love Toyota 4Runners” he found on Facebook. (He’s @idlebell on Twitter.) When I asked him about the nature of interaction in the group, he wrote:

I could post a video or picture of different problems. Or ponder possible solutions and have ten different people debating. Very specific advice. And now I jump in when relevant. For example, I contributed a trick to remove a difficult-to-reach bolt. Imagine. After 26 years discovering a new way to replace a bolt.83Over the years, a considerable literature has emerged espousing communities of practice. Oddly, nearly all of it leaves out something that Orr emphasized: the importance of noticing and honoring superior skill. Who are the best among us? What will it take for me to become one of them?

A major attraction of a community of practice is its role as an arena for recognition and endorsement by one’s peers. Orr showed how amicable competition among Xerox technicians built competence and spurred achieving mastery. That’s how the tigers were made. The communities discover best practices mainly by paying attention to their best practitioners.

I like what Wikipedia has to say about the “social capital” aspect of communities of practice. It says the communities create—and operate through--

a shared sense of identity, a shared understanding, shared norms, shared values, trust, cooperation, and reciprocity…. Unlike financial forms of capital, social capital is not depleted by use; it is depleted by non-use.84_________________________________